Dodd-Frank's Most Contested Financial Reform Makes A Quiet Entrance

The banking regulation that promised to hobble Wall Street’s biggest profit engines and force mega-banks to shed whole divisions came into effect Wednesday. But its official implementation made barely a peep.

Hailed as one of the central accomplishments of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Volcker Rule aims to curb some of the riskiest activities on Wall Street and make the financial system safer. Among other things, it prevents banks from engaging in proprietary trading, the use of federally insured deposits to make speculative bets on the markets.

It’s the kind of trading that played a signal role in the financial crisis, which saw billions of dollars in bank capital caught up in high-stakes gambles on mortgage products and other instruments.

But that’s not all the rule was intended to do. Paul Volcker, the former Federal Reserve chairman for whom it is named, said during the rule's drafting that it was meant to address “a cultural issue” in Wall Street. “This is speculative trading, but its influence goes far beyond the particular risks involved and particular transactions,” he said.

Lengthy Preparations

The extraordinarily complex rules were only finalized in 2013, after years of vigorous pushback from the banking lobby. The five federal banking regulators responsible for implementing the rule have only just begun their formal oversight, yet banks have been preparing for the change for years.

As soon as Dodd-Frank was passed five years ago, Wall Street began off-loading its proprietary trading desks. Goldman Sachs sold its operation to the private equity firm KKR in 2010. A storied unit of Morgan Stanley, PDT, spun off to become an independent hedge fund. In most cases, big banks lost significant drivers of profit.

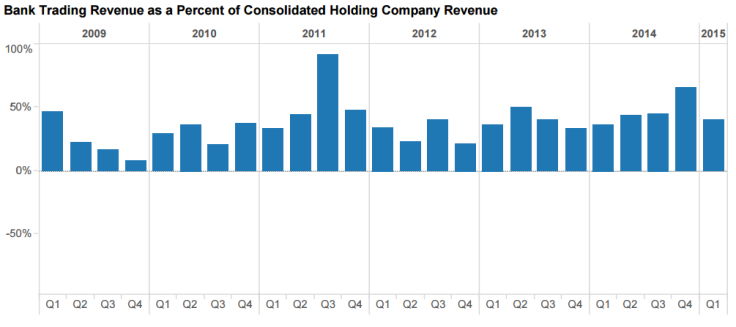

Since the big banks began shearing off their proprietary trading desks, however, total trading revenues have held relatively level as a percentage of overall revenue, with some quarter-to-quarter variability.

At the same time, smaller banks have scrambled to comply with the onerous requirements of the rule, some of which were lifted after heavy pressure from the industry. Other provisions of the Volcker rule have been delayed until 2017, including bans on owning stakes in private equity and hedge funds.

Recently, large financial firms have been ditching bond products called collateralized loan obligations, which bundle corporate debt to be sold to investors. The Volcker Rule prohibits banks from holding CLOs, as well as other so-called covered funds.

That doesn’t mean the likes of Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan will abandon trading such instruments completely, however. Exceptions in the Volcker Rule allow banks to continue their business of market-making -- buying and selling securities to trade with clients and other market participants.

Even with that carve-out, banks must limit their Volcker exceptions to a small percentage of their overall capital. Banks also may enter into positions as a means of insuring against losses in some other position.

Are Exemptions Loopholes?

Some lawmakers, like Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., have criticized these exemptions as loopholes, particularly the provision that allows risk-hedging trades.

Those concerns were elevated after JPMorgan’s “London Whale” fiasco, in which a British trader entered a series of highly risky positions in credit default swaps as part of the bank’s hedging strategy. When the strategy blew up, JPMorgan announced a $2 billion loss.

Merkley later joined other senators in assailing what they called the “JPMorgan Loophole,” which, they said in a letter, was “big enough to drive a ‘London Whale’ through.”

Like many aspects of the law, it’s not clear whether such a trade would be prohibited now that the Volcker Rule is in effect. The bank characterized the trade as a hedging strategy. “If you look at what we did in the Whale, we made a mistake,” JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon said in a conference call at the time. “We did a terrible thing. It was portfolio hedging badly done.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.