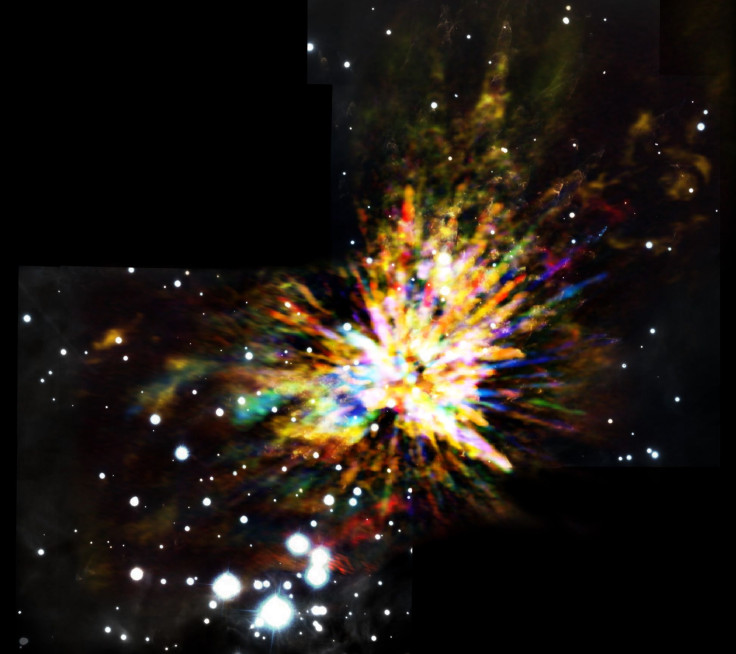

Explosive Star Formation Caught On Camera By ALMA About 1,350 Light-Years Away

The formation of stars can be a very explosive affair, in the most literal sense, new images taken by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in northern Chile have shown. Using the images, astronomers examined the debris caused by the explosion to better understand the result when two sibling stars collide in a stellar nursery.

The Orion Molecular Cloud (OMC-1) is one such star factory, located about 1,350 light-years away, part of the same complex as the Orion Nebula. Protostars began forming there about 100,000 years ago, and as they accumulated mass, some of them drew closer to each other due to gravity. And about 500 years ago, two of those stars touched each other — either just grazing by or colliding head-on — creating a powerful eruption that released as much energy as produced by the sun in 10 million years.

Read: The Early Universe Was Probably Making Stars Much Faster Than Previously Thought

Under the impact of that energy-intensive incident, the remaining protostars were launched out of the nursery at speeds over 150 kilometers (about 93 miles) per second, and sent “hundreds of giant streamers of dust and gas into interstellar space,” a statement on the ALMA website said.

“What we see in this once calm stellar nursery is a cosmic version of a 4th of July fireworks display, with giant streamers rocketing off in all directions,” John Bally from the University of Colorado and lead author on a paper — the paper, titled “The ALMA View of the OMC1 Explosion in Orion” and published in the Astrophysical Journal — said in the statement.

Bally and his team earlier observed the debris — first revealed using the Submillimeter Array in Hawaii in 2009 — in near-infrared, using the Gemini South telescope, also in Chile, which showed them the streamers extend almost one light-year from end to end.

“People most often associate stellar explosions with ancient stars, like a nova eruption on the surface of a decaying star or the even more spectacular supernova death of an extremely massive star. ALMA has given us new insights into explosions on the other end of the stellar life cycle, star birth,” Bally said.

Analysis of the images from ALMA would provide details about the distribution and motion of carbon monoxide inside the streamers spilling out from the site of the explosion. That, in turn, will allow scientists to “understand the underlying force of the blast and the impact such events could have on star formation across the galaxy.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.