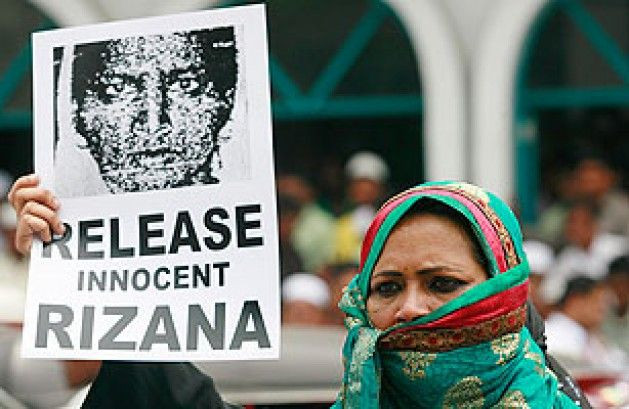

Fury In Sri Lanka Over Saudi Arabia’s Execution Of Young Domestic Worker; Would They Kill Westerners?

Human rights activists have condemned the Saudi Arabian government for executing a young Sri Lankan housemaid who was convicted of murdering an infant in her care.

Rizana Nafeek, a 24-year-old woman, was beheaded by a sword in public near Riyadh, the Saudi capital, on Wednesday, according to the Saudi Ministry of Interior.

The murder of the baby occurred in 2005, when Rizana was only 17 years old.

The president of Sri Lanka, whose repeated requests for clemency in the case were denied by the Kingdom, has also added his voice to the growing chorus of outrage against the relentless practice of executing domestic workers and other foreigners in Saudi Arabia.

On behalf of President Mahinda Rajapakse, the foreign ministry in Colombo stated: "[We] deplore the execution of Rizana Nafeek despite all efforts at the highest level of the government and the outcry of the people locally and internationally.”

The parliament in Sri Lanka observed a minute of silence to honor the dead girl.

International rights campaigner Human Rights Watch also condemned the act.

“Rizana was just a child herself at the time of the baby’s death, and she had no lawyer to defend her and no competent interpreter to translate her account [of the crime]. Saudi Arabia should recognize, as the rest of the world long has, that no child offender should ever be put to death” said Nisha Varia, senior women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch, in a statement.

“Saudi Arabia is one of just three countries that execute people for crimes they committed as children. Rizana Nafeek is yet another victim of the deep flaws in Saudi Arabia's judicial system.”

According to HRW, Rizana was employed by her Saudi employer for only two weeks when the 4-month-old baby named Naif al-Quthaibi under her care died. Initially, she confessed to the crime, but later retracted it, citing it was made under duress from the authorities. She claimed then that the infant died from choking while drinking from a bottle.

Contrarily, as reported by the Saudi Press Agency, the interior ministry asserted that Rizana smothered the baby to death after engaging in an argument with the child’s parents.

Rizana had been imprisoned in the Dawadmi jail in Riyadh province, since her arrest. In 2007, a court in Dawadmi sentenced her to death. The Saudi Arabian Supreme Court upheld the conviction and death sentence three years later.

The interior minister subsequently formally approved the execution, as required under Saudi laws.

In a bizarre and tragic twist, when Rizana applied to work in Saudi Arabia, a Sri Lankan recruitment agency lied about her age (alleging she was 23 instead of 17), so she could legally work in the Kingdom, by altering the dates on her passport.

Saudi Arabia, HRW noted, is breaching the terms of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which explicitly forbids the imposition of the death penalty for crimes committed before the age of 18. Saudi Arabia ratified that convention -- except when it conflicts with Islamic Shariah law.

The Saudis executed at least 69 people last year, HRW estimates.

With serendipity, the execution coincided with a report from the Geneva-based International Labour Organization (ILO) calling for greater protections for domestic workers around the world,

Of the more than 52 million domestic workers globally, only about 10 percent enjoy the protection of labor laws available to other workers.

The Sunday Times newspaper of Sri Lanka estimates that about 1.8 million Sri Lankans currently work abroad -- almost half of whom (45 percent) are women.

The Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) specifically blamed President Rajapaksha for Rizana’s execution.

“His office and the government … shamelessly neglected the life of this innocent Sri Lankan woman, who remained incarcerated abroad,” AHRC said in a statement.

“The Government of Sri Lanka [and] the office of the President did nothing to save Rizana's life, despite calls for assistance from Rizana's family and from the global civil society … The Government of Sri Lanka did nothing, except issuing valueless statements relating to this case.”

BBC reported that in Sri Lanka itself the tragic fate of Rizana has sparked discussions about the wisdom of sending migrants to work in the Middle East, as well as the poverty that pushes such people to seek work elsewhere.

HRW stated that Saudi Arabia has more than 8 million migrant workers -- accounting for half of the total workforce -- the overwhelming majority of them from Third World countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Philippines and Bangladesh.

Another prominent human rights organization, Amnesty International, reported that about one-half of the people executed in the Kingdom annually are foreign nationals from developing nations.

One Sri Lankan opposition MP, Ranjan Ramanayake, who had long campaigned for Rizana’s release, suggested that the Saudis were acting with racial and ethnic bias -- that is, the kingdom would never execute (white) Europeans or American for similar crimes. He also blamed the current Sri Lankan government for the death of Rizana, citing they have financial incentives not to protest too strongly against the Saudis.

"Rizana has paid for this ordeal with her life, while the real culprits who sent her [the recruitment agency] are not punished," he said, according to the Sunday Times newspaper of Sri Lanka.

"The [Colombo] government receives an income of six billion dollars from migrant workers but it hasn’t ensured their safety.”

However, Ramanayake’s claim that the Saudis do not execute foreigners from Europe and the U.S. may simply reflect the fact that (white) Westerners do not need to work as domestics in Saudi Arabia. They typically travel there to work as highly compensated petroleum engineers or other such white-collar professions, which likely provide far more prestige and protections than being a housemaid.

“The Saudi Arabians have not executed a Westerner for several decades,” said Jamie Chandler, a political scientist at Hunter College in New York.

“However, Western citizens are subject to the laws of the country, and could be executed if convicted of crimes that merit the death penalty. However, these types of cases also create diplomatic crises that may lead to the sentence not being delivered.”

Indeed, in March 2008, the Saudis sentenced Mohamed Kohail, a Canadian citizen of Saudi descent, to death in connection with the killing of a Syrian boy named Munzer Hiraki in a schoolyard brawl. Kohail was sentenced to a public beheading, but the case is currently on appeal.

“Canada is considering an appeal for clemency, but also changed its policy on defending foreign citizens,” Chandler noted.

“It will no longer come to the aid of Westerners who fall into legal trouble in foreign countries.”

In 2000, the Saudis arrested a dual UK-Canadian citizen named William Sampson for suspicion of having participated in two car bombings that killed a British man and injured several others. Sampson was imprisoned for almost three years and reportedly tortured by police. An employee of a Saudi government development bank, Sampson was eventually freed after enormous pressure from both British and Canadian diplomats.

Sampson died early last year in the UK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.