How Glaciers After Huge Antarctica Iceberg Will Affect The Sea Level

Icebergs breaking off Antarctica, even massive ones, do not typically concern glaciologists. But the impending birth of a new massive iceberg could be more than business as usual for the frozen continent.

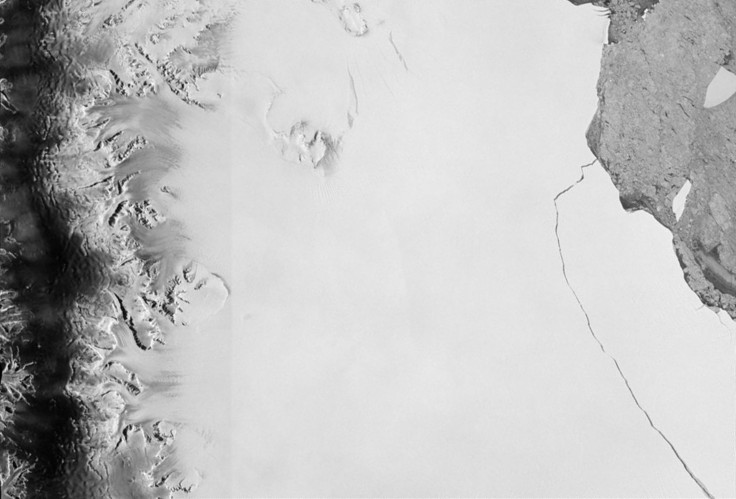

The Larsen C ice shelf, the fourth-largest in Antarctica, has attracted worldwide attention in the lead-up to calving an iceberg one-tenth of its area – or about half the area of greater Melbourne. It is still difficult to predict exactly when it will break free.

But it’s not the size of the iceberg that should be getting attention. Icebergs calve all the time, including the occasional very large one, with nothing to worry about. Icebergs have only a tiny direct effect on sea level.

The calving itself will simply be the birth of another big iceberg. But there is valid concern among scientists that the entire Larsen C ice shelf could become unstable, and eventually break up entirely, with knock-on effects that could take decades to play out.

Ice shelves essentially act as corks in a bottle. Glaciers flow from land towards the sea, and their ice is eventually absorbed into the ice shelf. Removal of the ice shelf causes glaciers to flow faster, increasing the rate at which ice moves from the land into the sea. This has a much larger effect on sea level than iceberg calving does.

While the prediction that Larsen C could become unstable is based partly on physics, it is also based on observations. Using aerial and satellite images, scientists have been able to track very similar ice shelves in the past, some of which have been seen to retreat and collapse.

The death of an ice shelf

The most dramatic ice shelf collapse observed so far is that of Larsen C’s neighbour to the north – the imaginatively named Larsen B. Over the course of just six weeks in 2002 the entire ice shelf splintered into dozens of icebergs. Almost immediately afterwards, the glaciers feeding into it sped up by two to six times. Those glaciers continue to flow faster to this day.

In our new study, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, we turn the clock back even further to look at the Wordie ice shelf, on the west coast of the southern Antarctic Peninsula, which began to retreat in the 1960s and eventually disappeared in January 2017.

Over the past 20 years, observations have shown that the main glacier feeding into the Wordie ice shelf, the Fleming Glacier, has sped up and thinned. Compared with the glaciers feeding Larsen B and C, Fleming Glacier is massive: 80km long, 12km wide, and 600m thick at its front.

We used historic aerial photographs from 1966 to create an elevation map of the Fleming Glacier, and compared it to elevation measurements from 2002 to 2015. Between 1966 and 2015 the Fleming Glacier thinned by at least 100m near the front. The thinning rate, which is the elevation change rate, rapidly increased: the thinning rate after 2008 is more than twice that during 2002 to 2008, and four times the average rates from 1966 to 2008.

Ice flow speeds have also increased by more than 400m per year at the front since 2008. This is the largest speed change in recent years of any glacier in Antarctica. These changes all point to ice shelf collapse as the cause.

We estimate the total glacier ice volume lost from all glaciers that feed the Wordie is 179 cubic kilometres since 1966, or 319 times the volume of Sydney Harbour. The weight of this ice moving off the land and into the ocean has caused the bedrock beneath the glaciers to lift by more than 50mm.

Other research has suggested this lift could have acted to slow the glacier’s retreat, but it’s clear that the bedrock deformation has not stopped the ice movement speeding up. It seems the Fleming Glacier has a long way to go before it will return to a new stable state (in which snowfall feeding the glacier equals the ice flowing into the oceans).

Fifty years after the Wordie Ice Shelf began to collapse, the major feeding glaciers continue to thin and flow faster than before.

We can’t yet predict the full consequences of the new iceberg calving from Larsen C. But if the ice shelf does begin to retreat or collapse, history tells us it is very possible that its glaciers will flow faster – making yet more sea level rise inevitable.

Chen Zhao, PhD candidate of Antarctic Science, University of Tasmania; Christopher Watson, Senior Lecturer, Surveying and Spatial Sciences, School of Land and Food, University of Tasmania, and Matt King, Professor, Surveying & Spatial Sciences, School of Land and Food, University of Tasmania

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.