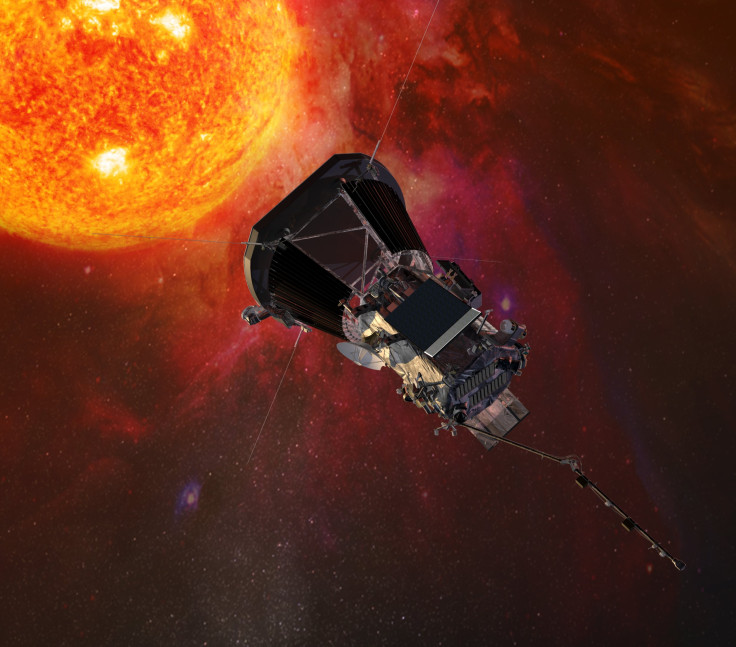

How NASA’s Parker Solar Probe Will Approach The Sun Without Melting

In a matter of weeks, NASA plans to launch an ambitious mission to "touch the Sun," where a space probe will head for our star and get closer to its surface than any other spacecraft has ever gone in the history of space missions.

The Parker Solar Probe will likely come within 3.8 million miles of the Sun’s surface, according to a release from NASA. It will fly through the outer atmosphere of the star, a region known as the Corona, and provide crucial information regarding the factors that drive a range of particles toward the Solar System and contribute toward millions of degrees of temperature, prevailing in the region.

As such temperatures are way beyond one’s imagination, survival of a spacecraft, even equipped with the finest of heat-shields, seems impossible — all the electronic components on board would melt away in no time. However, NASA is positive that its super-strong probe is going to make this journey.

The key, as the agency described, lies in the understanding of temperature and the effect it creates, aka heat. Temperature, which is way too high in this case, is a measure of how fast particles are moving, while heat is the amount of energy that these particles transfer to a given object.

In the emptiness of space, the particles move at high speeds but only a few of them transfer energy, which means they are not creating as much as heat the numbers on the scale suggest. This is similar to the case where a person feels more heat while putting his hand in hot water (due to the interaction with more particles) than in an oven heated to the same or higher temperature.

The same rule would apply to the Sun’s corona, which is not as dense as the star’s surface. Meaning, when the solar probe enters the atmosphere, it will only feel the heat on the scale of a few thousand degrees, roughly around 1,400 degrees Celsius (2500 degrees Fahrenheit).

While this is a big fall from millions of degrees, the resulting level of heat would still be high enough — nearly as hot as volcanic lava — to compromise the craft and its systems.

This is where the custom-made heat-shield — a sandwich of two carbon plates with carbon composite foam in between — developed by the agency would come in. The sun-facing side of the 4.5-inch thick shield will be painted in white ceramic to reflect as much as heat as possible and keep the other side, the spacecraft component, heated up to a mere 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit). It has been tested to withstand heat up to a whopping 1,650 degrees Celsius (3000 degrees Fahrenheit), as per the space agency.

Meanwhile, other components of the probe, especially those that would operate outside the protection of the shield, have been designed with materials capable of bearing any level of heat the Sun has to offer — heat levels well above 2,500 degrees Celsius (4500 degrees Fahrenheit). This would include tungsten made chips for producing an electric field for the instrument that would measure the flow of charged particles and niobium-crafted electrical wiring.

Also, in order to protect the vulnerable components placed behind the shield, the onboard sensors of the craft will keep correcting its course, ensuring that the parts do not face the Sun’s extreme heat. The agency will also use pressurized deionized water to keep the whole spacecraft cool during its adventurous trip.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.