Intercepted Russian Jets In Europe May Signal New Cold War, Or Just Plain Old Diplomacy

Scores of fighters and bombers were tracked over the Atlantic during a bold display of Russian air power starting Tuesday and lasting until midday on Thursday. This brings the total of Russian aircraft intercepted by NATO to more than 100 for the year, the Atlantic Council said, three times as many as in the whole of 2013. These most recent sorties, thought to contain as many as 26 aircraft, have underlined the strain that has developed between East and West, but not all experts are putting this down to just Russian aggression.

Igor Sutyagin, now a senior research fellow at London’s Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, and once part of a spy swap between the U.S. and Russia in 2010, says the perceived provocation from Russia is not about antagonizing other countries but about redefining Russia’s new standing in the world -- and even becoming “friends” with the West once again.

“Putin’s message is clear: 'Don’t mess with us, but we want to be friends',” Sutyagin said in a phone interview. “That message is now a matter of urgency as the Russian economy deals with the double problem of oil prices and the increasing price of the dollar, so he really needs this problem solved soon.”

NATO first began monitoring the aircraft on Tuesday afternoon and tracked multiple sorties over the next 48 hours. A spokesperson for the alliance stressed that the aircraft had not violated NATO airspace, but that the “sizable Russian flights represent an unusual level of air activity over European airspace," the alliance said.

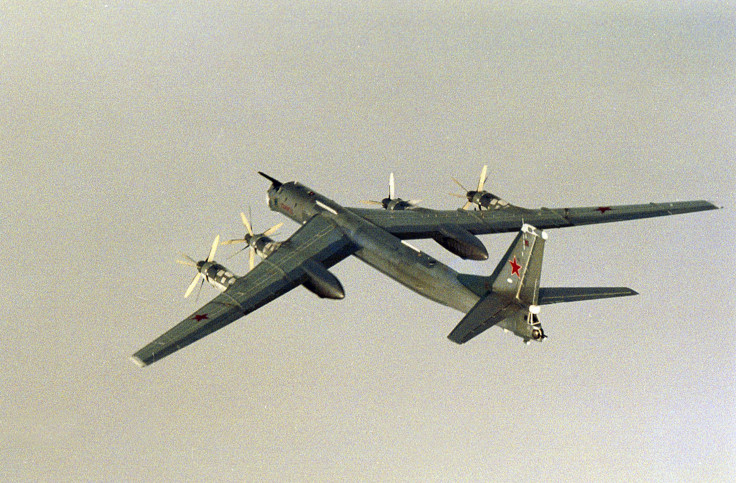

The biggest group, including four Tupolev Tu-95 bombers, a Cold War relic, flew out over the Norwegian Sea in the early hours of Wednesday, accompanied by four Ilyushin Il-78 refueling aircraft. Four Norwegian F-16s scrambled to intercept them, before six of the eight Russian aircraft turned back toward Russia. The remaining two bombers continued onward to the North Sea, where British Typhoon fighters were waiting. Portuguese F-16s also tracked the aircraft as they flew down the Atlantic, then back toward home.

Other incidents saw Russian fighter jets over the Black Sea, while several fighter jets were monitored over the Baltic.

And while it may seem inconceivable that flying fighter jets and bombers around Europe would be seen as anything other than aggressive, even in international airspace, Sutyagin pointed to a classic concept of international relations as another possible explanation for the flights. Russia, he said, is practicing what was known in the 19th century as "gunboat diplomacy" -- the equivalent today of sending warships not necessarily to use them to fire, but in order to secure an advantage or avert loss.

The theory was best described by British diplomat James Cable, who split it into four categories. "Definitive force" holds that governments used the gunboats to influence a decision or force a retraction (in Russia's case, pushing the West to remove or assuage sanctions imposed after the annexation of Crimea, Sutyagin said). "Purposeful force" is aimed at changing the policy or character of the target government. "Catalytic force" is designed to offer policy makers an increased range of options. And "expressive force" uses military action to send a political message.

It could be argued that Russia is deploying all of these options as it looks to deal with a range of political clashes, including Crimea, eastern Ukraine, relations with NATO and the U.S., and control over the Arctic, Sutyagin said.

In this case, Russia isn't using gunboats but its sizable and fairly modernized air force. With hundreds of newly delivered jets, bombers and helicopters in the country’s 61 airbases, Russia's aerial might is no secret to the West. President Vladimir Putin hopes, according to Sutyagin, that this will pressure the U.S. and NATO to change course and enable sanctions to be lifted while also making the point that Crimea is now part of Russia.

“When Putin meets the G20 on 15 November, he will say that for the sake of the global economy and the international world Russian sanctions need to be lifted and have business as usual,” said Sutyagin. “He wants the West to just accept the annexation of Crimea, as they did with South Ossetia and Abkhazia.”

The sanctions that Putin wants lifted stem from the annexation of Crimea, which Emma Ashford, a Russia analyst with the Cato Institute in Washington, says has been nearly forgotten after seven months. “The rhetoric coming from NATO, Europe and the U.S. is that Crimea is likely going to be part of Russia," she said. “They [Russia] are attempting to create what’s known as a ‘frozen conflict,’ the same conditions as was seen in the [2008] conflict with Georgia, which resulted in the creation of the semi-autonomous states of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.”

But despite Sutyagin’s belief that Russia’s actions are a form of diplomacy, others have perceived them as aggressive and provocative.

“We have been keeping track of incidents and have noticed an increase in Russian flights close to NATO airspace since the start of the Ukraine crisis,” said Lt. Col. Vanessa Hillman, a Pentagon spokeswoman. “We don’t think those flights help de-escalate the current situation at all.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.