Iraq's Sadr Must Work With Pro-Iran Groups To Choose PM

Firebrand cleric Moqtada Sadr may be Iraq's big election winner but he will still have to haggle with his opponents, linked to armed pro-Iranian groups, to forge a new government.

War-scarred Iraq -- an oil-rich country plagued by corruption and poverty -- last Sunday held its fifth parliamentary elections since the 2003 US-led invasion toppled dictator Saddam Hussein.

Sadr, a Shiite Muslim preacher who once commanded an anti-US militia, had campaigned as a nationalist and criticised the influence of big neighbour Iran, which has grown strongly since Saddam's fall.

The political maverick had initially vowed to boycott the polls but then sent his movement into the race, proclaiming in recent months that it will be he who chooses Iraq's next prime minister.

At first glance, his bloc's election win would seem to reinforce that view. The Sadrists won 70 out of the assembly's 329 seats, according to preliminary results, boosting their lead.

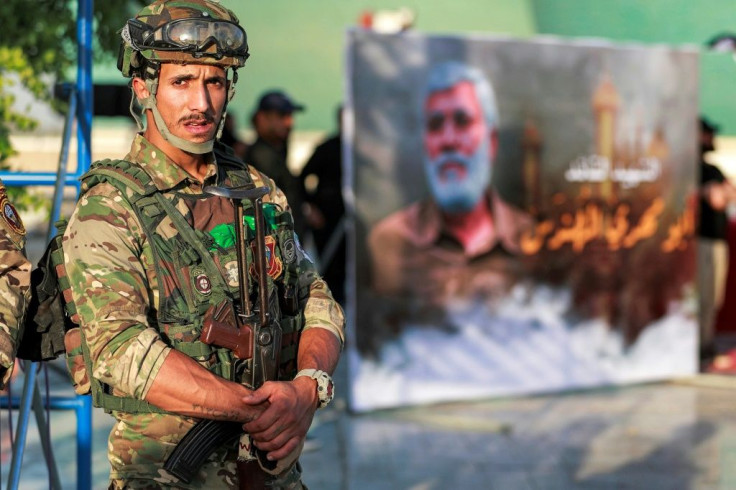

But analysts say Sadr will now have to come to terms with his adversaries -- the pro-Iran Shiite parties linked to the Hashed al-Shaabi network of paramilitary forces.

The Fatah (Conquest) Alliance, Hashed's political wing, lost more than half of its 48 deputies, according to preliminary results.

"The results give Sadr an upper hand when it comes to politics and his negotiating position, but that is not the only thing that is important here," said Renad Mansour of the Chatham House think tank.

The Hashed "has lost political power by losing seats, but they still have coercive power, and that will be used in the bargaining," he said of the movement, which according to estimates has over 160,000 men under arms.

Despite the implicit "threat of violence" Mansour does not predict an escalation, but he warned: "That doesn't mean that each side won't use threats and sometimes violence... to show that they have that power".

Iraqi politics have been dominated by factions representing the Shiite Muslim majority since the fall of Saddam's Sunni-led regime.

They are, however, increasingly split, especially on their attitude toward powerful Shiite neighbour Iran, which competes with the United States for strategic influence in Iraq.

The Hashed were formed in 2014 to fight the Sunni-extremist Islamic State group, and entered the legislature for the first time in the 2018 vote, after a major role in defeating IS.

Opposition activists accuse Hashed's armed groups -- which are now integrated into Iraq's state security forces -- of being beholden to Iran and acting as an instrument of oppression against critics.

A youth-led anti-government protest movement that broke out two years ago ended after hundreds of activists were killed, and the movement has blamed pro-Iranian armed groups for the bloodshed.

Washington, meanwhile, accuses Tehran-backed armed groups of being behind rocket and drone attacks on its military and diplomatic interests.

Among many Iraqis, the mood on Iranian interference has soured, and Sadr voiced that sentiment after the election.

He attacked "the resistance", the name pro-Iran armed groups give themselves in the Middle East.

"Arms should be in the hands of the state and their use outside of that framework prohibited, even for those who claim to be from the resistance," he said in a clear reference to Hashed.

The Hashed and their allies denounced the election outcome as a "scam".

"These elections are the worst Iraq has known since 2003," charged the head of Houqouq, a party close to the Hezbollah Brigades which are under the Hashed umbrella.

The faction's military spokesman accused Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhemi of being the "sponsor of electoral fraud".

Amid the heated rhetoric, the political blocs are seen to be starting the process of post-election haggling aimed at forming parliamentary blocs ahead of finding a prime minister.

One pro-Iran figure and Hashed partner made surprising gains -- former prime minister Nuri al-Maliki, who served from 2006 to 2014 and whose State of Law Alliance can count on more than 30 seats.

Fatah is looking at Maliki's party and smaller groups to create the largest parliamentary bloc and nominate him as prime minister, said Hamdi Malik, of the Washington Institute for Near East Study.

"This is very hard to achieve, but it can form their starting point to enter into negotiations with Sadr to secure a lot of positions in the next government," Malik said.

The most likely outcome, the analyst added, is "a compromise PM with a lot of Sadrist control over him".

Political scientist Ali al-Baidar said that, whatever happens, Hashed won't be content sitting in opposition.

"There is no culture of opposition in Iraqi politics," he said. "Everyone wants some of the power."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.