ISIS’ Operational Capacities In Turkey Strengthened By Laissez-Faire Approach Of President Erdogan's Government

BEIRUT — Tuesday's bomb blast at the heart of Istanbul sent shock waves through Turkey's second city. A suicide bomber, said by Turkey to be affiliated with the Islamic State group, detonated his explosives at a popular tourist site, sending shrapnel flying into historic Sultanahmet Square, killing at least 10 people, all of them foreigners, and injuring 15 more. The attack marks the first bomb targeting tourists that Turkey has seen in recent history.

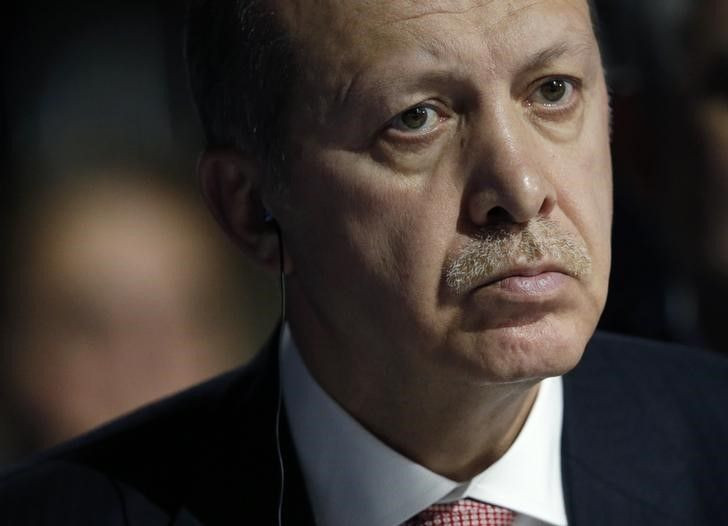

Within four hours of the bombing, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that the suspected suicide bomber was of Syrian origin, which Deputy Prime Minister Numan Kurtulmus confirmed shortly after. Four hours later, the independent Turkish Doğan News Agency reported that the suspect was not Syrian, but a Saudi national by the name of Nabil Fadli. It took only 20 more minutes before Erdogan and Kurtulmus announced that the 28-year-old was a member of the group also known as ISIS and had recently entered Turkey from Syria.

Despite Erdogan’s claims, some residents of Istanbul — both Turkish and Syrian nationals — remained skeptical.

“How has he been identified so quickly and what is the evidence that this person is Syrian?” Fares Kazb, a Syrian national living in Istanbul with ties to the Syrian opposition, told International Business Times. “Syrian people are peaceful and not everyone is a terrorist. If a person was born in Syria, it’s not because he committed a sin but because God wanted him to be born in Syria and not in another country.”

#Turkey authorities ban on Turkish media reporting on blast, as usual. They never realise people need information at a time of crisis

— Mark Lowen (@marklowen) January 12, 2016The local media blackout that the government imposed in the hours after the attack has not restored faith in Erdogan's proclamations. Mina, a 24-year-old Istanbul resident who asked that her last name be omitted for security reasons, could not find any coverage on local television. Mina came to know of the attack and the allegations, like many of her friends and family in Istanbul, through social media platforms and official government statements.

“I just saw that a bombing occurred, I wanted to know where, how many people, and specifically what Turkey was saying about it,” Mina told IBT. “The Turkish people are [consistently] fed wrong information according to the current government's agenda.”

ISIS Attacks on the Rise

Explosive attacks that are directly linked to ISIS leadership have so far been rare in countries outside the territory it controls in Iraq, Syria and Libya. Turkey is an exception and has had two major bombings in the last year with suspected ties to ISIS. Whether the attack was a result of a direct order from ISIS leadership in Iraq and Syria or a lone-wolf offender inspired by ISIS has yet to be confirmed, and ISIS has not claimed responsibility for the bombing.

“Turkey has such a robust [ISIS] recruitment infrastructure. You have people who are living in Turkey, who want to continue living in Turkey but are very much networked with ISIS,” Harleen Gambhir, a counterterrorism analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, told IBT. “If there are elements of that infrastructure who want to launch attacks, the question becomes ‘What’s the best way for them to do so?’ Do they cross the border … or do they try to launch their own attacks in Turkey?,'" Gambhir said.

Silence from ISIS is not unusual when it comes to attacks in Turkey.Turkey's two previous ISIS-linked bombings have been tied to a militant cell in southern Turkey that's likely linked to the group's headquarters in Syria through methods of recruitment, Gambhir said, but may not be receiving direct orders from ISIS leadership to launch attacks.

One of the challenges of evaluating the true extent of the ISIS threat is that Turkey's 565-mile border with Syria is porous, and, for the last four years, has effectively operated as a revolving door for jihadis hoping to fight with ISIS and other groups. Erdogan's government has faced international criticism for failing to stem the flow of foreign fighters crossing the border into Syria, but now the terrorist threat to Turkey also comes from within the country and isn’t limited to ISIS.

Turkey is a NATO member and key partner in the anti-ISIS coalition, having stepped up its involvement last summer when it allowed the U.S. to strike terrorist targets in Syria from Turkey’s Incirlik air force base, just 250 miles from ISIS’ de facto capital Raqqa. At the same time, Turkey has supported al Qaeda-linked groups in Syria and has been accused of tacit acceptance of certain ISIS branches that are fighting Kurdish groups.

Turkey's Many Enemies

“The real problem for the Turks is that their enemies have multiplied over the course of the Syrian civil war,” Nicholas A. Heras, a Middle East researcher at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) and an associate fellow for the Jamestown Foundation, said. “Their enemies now have a form of leverage against them, which is the ability to strike at the heart of Turkey’s tourist economy.”

Turkey’s intelligence agency issued two separate warnings on Dec. 17 and Jan. 4 that Turkish members of ISIS were “in preparation” for various operations inside Turkey, including spots frequented by foreign citizens and tourists, according to a report from the Hurriyet Daily News.

Although Turkey has taken steps to control the border, experts said Turkish law enforcement has been slow to enforce security measures on fighters already residing in, or returning to, Turkey.

The government is aware of an ISIS cell active in the southeastern Turkish city of Adiyaman and goes by the English name of “Weavers.” And a majority of the group’s members are believed to have traveled to Syria between 2013 and 2014 where they trained and fought alongside militants who were to later become ISIS. But Turkish security forces have enabled the cell to continue, in large part because they share a common enemy: the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a Turkish Kurdish armed group that has long been in conflict with Turkish nationalists and, more recently, with ISIS.

“The more insidious problem is that it does not appear that Turkey has taken an active strategy to dismantle ISIS’ facilitation networks inside of Turkey,” Heras said. “If you’re not [allowing] foreign fighters to flow [out of Turkey and into Syria], then local communities are [ISIS’] next target.”

ISIS in Turkey has done just that — setting up shop in a local Turkish community right on the border with Syria. Gaziantep is a crowded Turkish city that used to be famous for its pistachios but has since turned into a haven for Syrian militants and foreign fighters. Despite a recent uptick in arrests and the government’s decision to close the official border crossings, ISIS fighters were still able to run a cross-border human smuggling operation until this past summer.

“If Turkey wants Daesh to enter, Daesh will enter Turkey. Daesh will not intervene in Turkey,” said Kazb, an aspiring Turkish journalist, using the Arabic acronym for ISIS. “Why [is] the Turkish border with Daesh open, and the border with the rebels [is] closed?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.