Japan Tsunami Slices Off Manhattan-size Icebergs in Antarctica

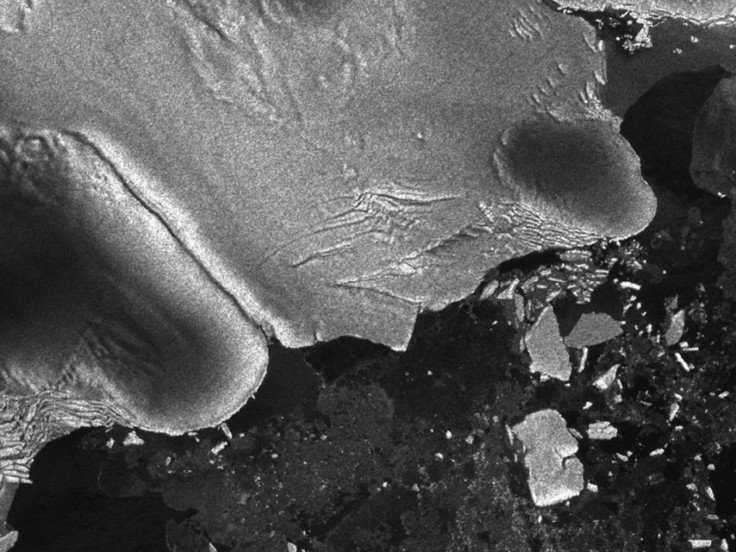

A powerful tsunami in Japan back in March sent waves more than 8,000 miles away that sliced off icebergs in Antarctica twice the surface area of Manhattan, NASA scientists say.

Details of the finding, the first observation of its kind, can be found in an article published in the Journal of Glaciology.

The 9.0-magnitude earthquake killed tens of thousands of people and destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture.

When the Tohoku Tsunami was triggered in the Pacific Ocean, Kelly Brunt, a cryosphere specialist at Goddard Space Flight Center, and her colleagues were able to spot new icebergs floating off to sea shortly after the sea swell reached Antarctica.

The swell was likely only about a foot high when it reached the Sulzberger shelf, but the consistency of the waves produced enough stress slice the glacier.

The icebergs broke away because there were huge waves exploding from the epicenter of the earthquake.

NASA said historical data showed that this particular piece of ice hadn't moved in at least 46 years prior to the tsunami. Scientists were able to watch the Antarctic ice shelves in as close to real time as satellite imagery allows, and catch a glimpse of a new iceberg floating off into the Ross Sea.

"In the past we've had calving events where we've looked for the source. It's a reverse scenario - we see a calving and we go looking for a source," Brunt said in a statement. "We knew right away this was one of the biggest events in recent history - we knew there would be enough swell. And this time we had a source."

The largest iceberg was about four by six miles in surface area, which is about equal to the surface area of one Manhattan.

The breakaway of the iceberg ended scientists speculations that such an event could happen and at the same time provided some light on knowledge of past events.

"In September 1868, Chilean naval officers reported an unseasonal presence of large icebergs in the southernmost Pacific Ocean, and it was later speculated that they may have calved during the great Arica earthquake and tsunami a month earlier," Emile Okal at Northwestern University said. "We know now that this is a most probable scenario."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.