Judge’s Surprise Ruling On Veteran’s Exposure to Toxic Chemicals On U.S. Military Base Called “Turning Point”

For the past decade, U.S. Army veteran Steve House has been on a mission. Riding the highways of America from Oregon to Virginia on his Harley, he has visited dozens of fellow vets and medical and military experts to hear their stories and collect information to bolster his claim that he is entitled to disability payments after being exposed to toxic chemicals during his service in the late 1970s.

House, 56, a burly, deep-voiced man with a long beard and ponytail who was stationed at Camp Carroll in South Korea, suffers from diabetes, liver disease, glaucoma, neuropathy and other illnesses. He has been locked in a bitter, protracted battle with the Department of Veterans Affairs over his claim that his illnesses are linked to his work burying 250 barrels of Agent Orange, the toxic defoliant, in 1978 -- three years after the last Marines left Vietnam.

House has doggedly pursued any information that might help get his claim approved and prove to VA that he’s not fabricating his exposure. His claim was repeatedly denied by the VA until last week, when a judge with VA’s Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA) acknowledged that House’s suffering resulted from chemical exposure at Camp Carroll, though it stopped short of naming Agent Orange.

“I was determined to show that I was telling the truth about why I’m so sick,” House said. “I gave up countless hours of my life, including years of my vacation time that I should have spent with my family, digging for facts. I have a very understanding wife. I had to do what I had to do.”

The VA portrayed the ruling as a single administrative finding that applies to this one man. But House and others who have long alleged a government cover-up regarding Agent Orange and other toxic chemicals say it is an acknowledgement of the malevolent consequences of veterans’ exposure to those chemicals, even if, at this stage, it is unclear how the ruling will affect cases that are specifically about Agent Orange.

Rick Weidman, executive director of government affairs for Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), called the judge’s decision on House’s claim historic. “It’s a precedent, a real turning point that we haven’t had before,” Weidman said. “Despite the fact that VA is still not saying that Agent Orange was buried there, virtually no one to date has gotten recognition for exposure to toxic chemicals, Agent Orange or otherwise, outside of the war zone. VA finally admits they sprayed Agent Orange along the DMZ [in Korea], but as far as toxins harming veterans at any other location, they very rarely admit it.”

“I won,” House said flatly. “It’s good news and I’m grateful. But I have mixed emotions about it. I feel kind of numb. My fight isn’t over. There are a lot of my buddies out there who were also at Camp Carroll who are sick now and that I hope to help.”

In a bluntly worded, 18-page court document, BVA Judge K.J. Alibrando acknowledged that Camp Carroll was contaminated with pesticides, PCBs, TCEs and heavy metals, and that these chemicals harmed House. The ruling did not cover Agent Orange, but Alibrando granted House “service connection” for most of his variety of serious health issues, pending some routine physical exams.

“They granted me pretty much everything down the line. It’s very rare,” said House, who can’t work but currently has only a 30 percent disability rating. “Of course I wish VA would acknowledge that we buried that Agent Orange. We know what we were ordered to do on that base. But at least VA now admits there were toxic chemicals there that harmed me. This is a victory.”

Weidman said House had “the best-documented case of toxic chemical exposure outside of Vietnam of anyone I have ever seen, by far. He’s an extremely bright guy. He just had too much documentation; the facts were on his side. His case shows that the Department of Defense and VA’s story about toxic exposures to troops on U.S. military bases is starting to unravel.”

By contrast, a VA spokesperson told IBTimes that House’s disability case will have no influence on other cases.

“Pursuant to regulation, decisions issued by the Board of Veterans’ Appeals [Board] are nonprecedential in nature,” said the spokesperson, Meagan Lutz. “This means that decisions by the board are considered binding only with regard to the specific case decided. Each case presented to the board is decided on the basis of the individual facts of the case, with consideration given to all evidence of record, in light of applicable procedure and substantive law.” Lutz added that the percentage House receives for his disability rating “will be determined based on the nature and severity of his service."

Agent Orange, which was used by the DOD during the Vietnam War, had devastating effects on U.S. troops as well as Vietnamese civilians. The herbicide has been scientifically linked to several types of cancer as well as Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, skin problems and other diseases and conditions, many of which House now suffers with.

To date, disability claims from veterans like House who said they were exposed to Agent Orange and other chemicals have mostly been limited to those who served in Vietnam and in a few select places, including the Korean DMZ – not other military bases.

While the judge's ruling does not directly affect Agent Orange cases, House and Weidman believe that it sets a precedent, and will help focus renewed attention on veterans’ exposure to toxic chemicals, including Agent Orange.

The Marine Corps Times reported last week that Maine Gov. Paul LePage is expected to sign into law a bill calling on the federal government to recognize disabilities suffered by Maine soldiers who were exposed to Agent Orange at a military base in Canada. The bill, sponsored by Democratic Sen. John Tuttle, focuses on potential exposure by Maine Army National Guard members at Canadian Forces Base Gagetown in New Brunswick. Fields at the base were sprayed with chemical herbicides, including a small amount of Agent Orange, according the the Marine Corps Times.

There is growing evidence that Agent Orange was used before, during and after the war on U.S. military bases across the globe, and that it contaminated troops after the war in Air Force planes that had been used in Vietnam to spray the defoliant.

House, whose father served in the Korean War, said he hopes his case will lead to more awareness of toxic dumps on U.S. military bases, and in particular, that Camp Carroll is “just another Camp Lejeune," referring to the North Carolina Marine base where service members and their families were exposed to solvent-contaminated drinking water from 1953 to 1987. "It’s toxic and people who were stationed there have been harmed, as have the civilians who live near the base. Our bases are toxic and are hurting veterans, and the public needs to know this. I hope this decision by the judge will lead to more decisions for other veterans who were stationed there and are now suffering.”

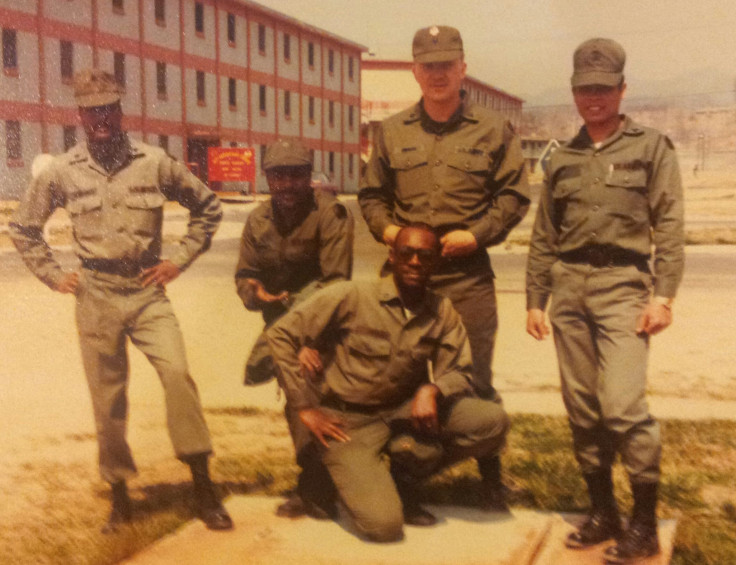

Ailing Army Vet Charles Powell

Among those suffering veterans is Charles Powell, who was stationed at Camp Carroll from 1981 to 1982. A truck mechanic who hauled supplies across Korea, Powell worked on the site where House said he buried Agent Orange a few years before. Last year, Powell was diagnosed by VA doctors as having stage IV colon cancer. He is currently undergoing chemotherapy but does not have a disability claim with VA for either his cancer or his severe skin rashes and bleeding. He said he plans to file one now that House has won his case -- not for the colon cancer, but for his chronic skin problems.

“In the last two years, since I found out about Steve [House], I’ve discovered 13 other veterans who were stationed at Camp Carroll after Steve was there, and we all have health problems,” Powell told IBTimes. “Many of us have exactly the same kind of skin issues: really bad, bleeding sores and blisters on our hands and feet.”

Powell is being treated at Williams Jennings Bryan Dorn Veterans Medical Center in Columbia, S.C., where as many as 20 veterans who were waiting months for simple gastrointestinal procedures -- such as a colonoscopy or endoscopy – died because their cancers were not caught in time. He said that, like House and others he has talked to who were at Camp Carroll, “My blisters and sores on my feet were so bad I had to change socks four times a day. I could hardly walk and am often unable to wear shoes. There is so much contamination at Camp Carroll, even without putting Agent Orange into your complaint, there were so many other toxic chemicals dumped on that base. I was personally ordered to dump oil in the creek and other places there.”

Powell, who became an award-winning photojournalist after his stint in the army, remembers looking out at the area on the base where House said he buried the Agent Orange.

“It was all dead,” Powell recalled. “The rest of the base was very green with trees and grass, but there was no grass growing on that valley. I asked my platoon sergeant why it looked so different than the rest of the base, and he said it was because it had been used for rice paddies and then they filled it in. I didn’t know until years later that this wasn’t true. He was not telling the truth, either.”

House said he feels responsible for Powell. “I was following orders, but I can’t help but feel somewhat responsible; he was probably drinking water I helped contaminate. He said I was following orders, he said it was not my fault. But I really hope he gets well.”

Peggy Knotts, Camp Carroll Vet and VA Employee

Peggy Knotts, who’s worked at VA as a graphic designer since 1989, was an army specialist stationed at Camp Carroll from 1983 to 1984. After her service ended, she returned to the United States and gave birth to a baby three months early who weighed one pound; her other two babies weighed about five pounds each. Knotts says she has also had severe headaches and mysterious and chronic muscle pain since her time at Camp Carroll.

Though Knotts filed a claim for an unrelated broken foot, which was first denied but later approved, she’s never tried to file a disability claim for her other conditions because, she says, VA doctors told her that none of them are on the presumptive list as connected to Agent Orange or other chemical exposures. “We know toxic chemicals cause muscle issues, but only Parkinson’s disease is on the VA list,” Knotts said. “There are lots of studies out there, but no proof. But I do believe that some of the health issues I am dealing with are connected to my time at Camp Carroll.”

Knotts said she plans to ask VA for a toxicology physical. “I resent that they knowingly let our troops and the people in the village outside the base drink water that they knew was contaminated. They never told us to avoid it. Steve’s case could help me and others file a claim. Once they set a case precedent, lawyers often refer back to those cases. I applaud him for what he has done.”

Weidman said babies with low birth weight or who are born prematurely are often connected to Agent Orange exposure. “There are many, many examples of families who have babies with birth defects, others had low birth weight, and they were exposed to Agent Orange,” Weidman said. “We believe low birth weight and premature babies are both connected to Agent Orange. But VA doesn’t spend any money on Agent Orange research. So we don’t know all of the answers and how many things are really connected.”

Anthony Hardie, a service-disabled Gulf War veteran and veterans advocate who’s testified before Congress many times, applauded House for his tenacity, and pointed out that veterans have been exposed to toxic chemicals in every war, from World War II to Vietnam to the Gulf War to the current war in Afghanistan.

“I'm relieved to hear that this veteran won what was owed to him, though it only came after years of battling the VA,” Hardie said. “However, his case is just the tip of the much broader issue of toxic wounds from military service, including exposure to Agent Orange and other dioxin-laden herbicides, the 1991 Gulf War toxic soup, contaminated vaccinations, burn pits, solvent-contaminated drinking water at Camp Lejeune, and much more.”

Hardie said DOD and VA have a “long history of lying to our troops, veterans and the public about contamination, safety, health risks, and actual health outcomes. As the old saying goes, an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and this is especially true in the cases of toxic wounds like House’s, where DOD’s record-keeping of toxic substance creation, storage, use and human exposure has been notoriously awful.”

The appeals judge in House’s case, who cited House’s research and documentation showing that Camp Carroll was contaminated, noted in his decision that following House’s allegations, the Army conducted an extensive joint U.S.-Korean investigation in 2011 that concluded the Carroll site had been used to bury numerous chemicals, but not Agent Orange.

The report from that investigation found that drums of pesticides, herbicides and solvents were buried in Area D, where House said he buried the Agent Orange, in 1978. The judge also noted that investigators said there were a number of toxic chemicals present in groundwater and soil samples at Camp Carroll, including “pesticides and volatile organic compounds (VoCs) such as PCE, TCE, benzene as 1,2,4 trimethylbenzene, and 1,2,2,2-tetrachlroethane.”

The judge wrote that some of these materials were excavated from 1979 to 1980 and shipped to an unidentified location: “This was verified in an interview with the former transportation officer for Camp Carroll in 1979. He specifically described the preparation that was undertaken to ship chemicals that had been excavated.”

House argues that the judge relied too much on the investigation and its witnesses. “That so-called thorough investigation never even interviewed Richard Kramer, my buddy on the base who helped bury the Agent Orange and is now sick as a dog,” House said. “They also never interviewed my squad leader, who knows what we buried and whose first son was born a diabetic. He never filed a claim. They say they interviewed 177 people, mostly Koreans, but why did they not talk to the guys who know more than anyone else? They say it was a complete investigation, but it wasn’t.”

America’s Toxic Military Bases

Multiple reports suggest that U.S. military bases are toxic, and that Agent Orange was stored, used and buried during the war and afterward on U.S. sites from Guam and Okinawa to Fort Ord in California and Ford Detrick in Maryland, the so-called birthplace of Agent Orange, where it was tested and some veterans were allegedly harmed.

More than 1.4 million gallons of Agent Orange was brought to Okinawa from Vietnam before being taken to Johnston Island to be incinerated, according to this army document. And the toxic legacy at Okinawa is still making news. Recently at the Kadena (U.S.) Airbase in Okinawa, highly toxic compounds were discovered at a dump site near two schools for children of U.S. military. Also, military records related to Agent Orange reportedly show an herbicide stockpile at Kadena in 1971.

Weidman, who will welcome House this week to Washington, D.C., for the VVA’s spring board of directors meeting, said the veterans group has been compiling evidence of toxic chemical use by the military “just about any place in the Pacific and almost all the locations in the continental United States. We have quite a tome now on bases in Korea, Guam, Okinawa, Japan, the Philippines and more.”

Weidman described House as a hero. “As sick as he is, he is such a bull in terms of strength, to be able to keep going as he has,” he said. “The average bear would have died a long time ago. Steve has a tremendous will and spirit. The guy is the genuine article. Our hope is that he will continue to work for the benefit of veterans.”

As for ailing veteran Powell, he’s happy for his old friend House but remains angry at his government. “So many of us were lied to about Camp Carroll, it’s a shame and a disgrace,” he said. “When Steve buried the Agent Orange in 1978, he was digging up stuff that was already there. It’s been a landfill since the 1950s. There’s no telling what thousands of veterans have been exposed to there and other bases over the years.”

Now that House has won his case, Powell said, “I will proceed with a claim and see what happens. I am fighting cancer right now, but I’m willing to do what I can to help my family and other veterans. I’m sure there are people more deserving than I am. I wonder how many more of my fellow veterans are having the same problems.”

House said the same standard that the judge applied to him should apply to people like Powell who’ve been adversely affected by the exposure they received while in the army. But it is not clear that will be the case.

Robert Walsh, a Michigan attorney who has had hundreds of clients who were exposed to toxic chemicals at U.S. bases (he did not represent House), said this decision could get that ball rolling, but that, “VA is idiosyncratic. Each case does not necessarily impact another. However, given the strength of the ruling, Allison Hickey [VA’s under secretary for benefits] can issue a letter saying all chemical exposure claims from Camp Carroll can be granted. She could do this today. Short of that, if others at the base who were exposed and harmed attach the decision by the judge in House’s case, and House’s doctors also look at these others who were exposed and confirm their health issues, they do have a better chance now of getting their claims approved. But VA being VA, it’s no guarantee.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.

Join the Discussion