Liver Stem Cells' Source Discovered By Scientists

Scientists have identified the prototypical stem cells that grow into liver tissue, ending a longstanding mystery about where the liver replenishes dying cells from.

Scientists from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Stanford University found the source of highly specialized liver cells known as hepatocytes that are responsible for storing vitamins and minerals, removing toxins and regulating blood-borne fats and sugars. Hepatocytes in the liver are constantly dying and being replaced, but the source of the new cells had remained unknown so far.

Previously, scientists had speculated that hepatocytes maintain their population by dividing, instead of being replaced by stem cells. Stem cells are undifferentiated and unspecialized cells that can transform into several types of cells.

However, lead researcher Roel Nusse said that mature hepatocytes are so specialized that they have lost the ability to divide -- they have “amplified” their chromosomes to increase their ability to perform tasks, but it cost them the ability to divide into other cells.

"We have solved a very old problem by showing that like other tissues that need to replace lost cells, the liver has stem cells that both proliferate and give rise to mature cells, even in the absence of injury or disease," Nusse said in a press release. The results of the research were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

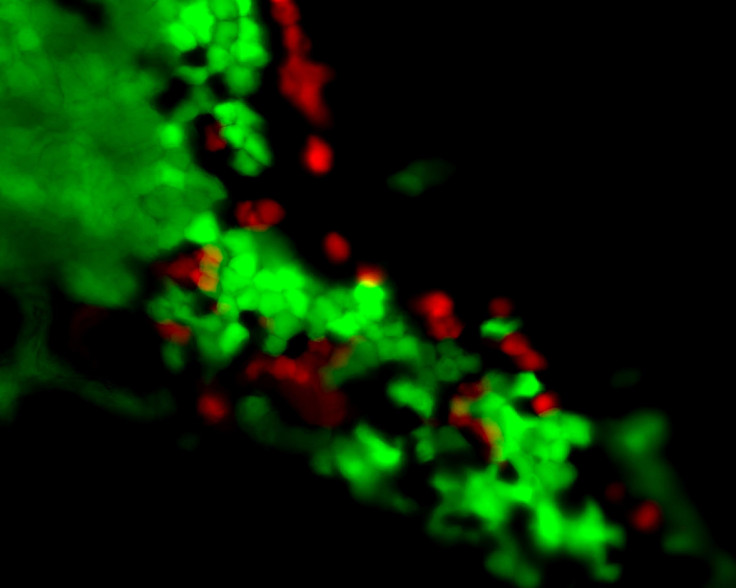

For their study, the scientists focused on a class of proteins called Wnts, which are responsible for regulating stem cell specialization. They created genetically engineered mice in which Wnt-sensitive cells are labeled with fluorescent proteins, allowing them to track stem cells across several different types of tissues.

Visiting scholar Bruce Wang led an experiment in Nusse’s lab in which researchers looked for Wnt-responsive cells in livers of the mice, and found them around the organ’s central vein.

Once they had identified these cells, they tracked their behavior, and found that they were dividing rapidly, constantly replenishing their own population. The researchers found that these cells, unlike mature hepatocytes, did not have amplified chromosome expression. Tracking the progress of the cells’ descendants over a year, the researchers found that they had changed, taking on the specialized properties of mature hepatocytes.

The research team also found the mechanism through which the cells around the vein became specialized -- the endothelial cells lining the central vein released Wnt molecules, and stem cells that migrated out of reach of that signal became specialized and lost their ability to divide. “This fits the definition of stem cells,” Nusse said in the statement.

Nusse's team is now investigating whether the findings could help identify how these cells contribute to the regeneration of the liver after an injury, which they believe could help develop new medicines.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.