Marijuana Legalization In Colorado: How Recreational Weed Is Attracting People, But Spiking The State’s Homeless Rate [PART ONE]

EDITOR'S NOTE: For part two of this story read “Marijuana Legalization: Pot Brings Poor People To Colorado, But What’s Being Done To Help Them?”

Devin Butts walked the tiled halls of the Pueblo Mall early one Friday morning in April, amazed at what he saw. The mall, the main shopping center for the city of Pueblo in southern Colorado, was larger than anything the 25-year-old was used to while living on the streets of quiet prairie towns in north central Texas. He wandered through T-shirt stores and schlocky gift shops, past American flag-adorned beer bongs and marijuana-emblazoned “Rocky Mountain High” shirts, not noticing how employees warily eyed his baggy jeans and the tattoos peeking out from the sleeves and collar of his Bob Marley T-shirt. Or maybe he’d learned from experience to ignore the looks.

“Are you hiring?” Butts inquired at shop after shop. Often he received an apologetic shake of the head. Sometimes he was told to fill out an application online, no easy feat for someone who didn’t own a computer. At one store, a manager told him they were accepting resumes. “Resumes…” he responded, sounding perplexed, as if the thought of compiling a CV had never occurred to him.

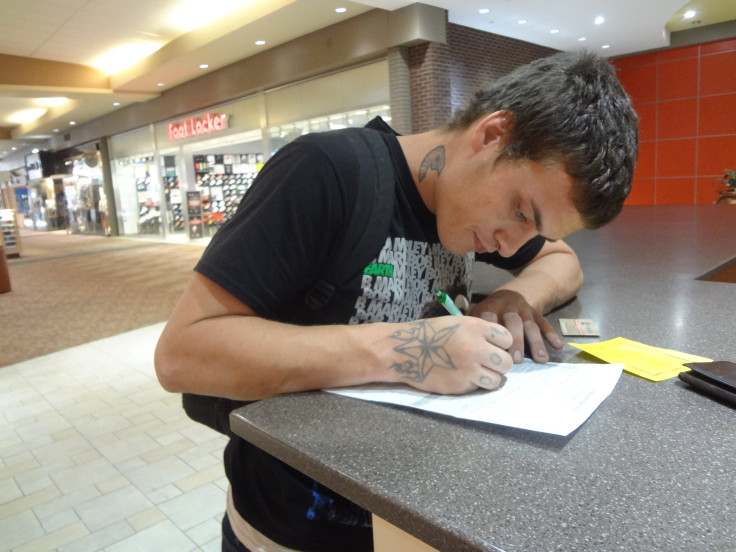

At a shoe outlet, a worker handed over a job application. Finding an empty mall kiosk down the way, Butts pulled out a pen and hunched over the questionnaire. Place of residence? For the past day, that would be the Wayside Cross Rescue Mission near downtown. Work history? That was where things got complicated. There was no way to properly list the various odd jobs he’d had over the years without explaining what had happened in between: the time spent in and out of jail, months lost to one hard drug or another.

If only there was a place on the application for Butts to explain what he was doing here, why 48 hours ago, he’d hopped on a Greyhound bus in Wichita Falls, Texas, a hit of meth in his system, and ended up in Pueblo, a city he knew nothing about, spending his first night here shivering between the dumpsters behind the rescue mission because he’d arrived too late to score a bed. If only he could properly explain that his plans for hope and prosperity were tied to marijuana, something that had been a part of his life, for better and worse, since he was a young teenager. He’d come to Colorado, a state famous for legalized cannabis, because he’d decided that cannabis would be the only indulgence he would keep as he tore himself away from all the other, far more dangerous substances and habits he was used to.

While much has been made of the tourists, entrepreneurs and investors lured to Colorado’s blossoming marijuana industry, very little attention has been paid to another population drawn to the state’s cannabis experiment: marijuana migrants moving to the state who wind up on the streets. Interviews with people at homeless shelters in Denver and other Colorado cities like Pueblo suggest that since Colorado launched its legalized cannabis system in 2014, the percentage of newcomers to the facilities who are there in part because of the lure of marijuana has swollen to 20 to 30 percent.

All told, several hundred marijuana migrants struggling with poverty appear to be arriving in Colorado each month. Some of them, like Butts, come to use cannabis recreationally or medically without the fear of arrest. Others are hoping to get jobs in the new industry. But many arrive to find homeless services stretched to the breaking point, local housing costs increasingly prohibitive and cannabis use laws that penalize those without private residences.

Fresh off the bus from Texas, Butts didn’t know any of this. He was still optimistic that legal marijuana would be his lifeline as he struck out on a new path. “I’m going to get clean, man,” he said. “That’s what the marijuana industry is for. I think being here in Colorado is going to help.”

“It Looks Like Something Out of ‘Grapes of Wrath’”

Butts had stepped off the bus in Pueblo carrying very little: a few pairs of pants, socks, underwear and his red leather Bible, the only personal memento he kept. “I figured if I was going to start over, I should leave everything behind,” he said.

That's the way Butts is: upbeat and forward-thinking, not one to dwell on the struggles of his past, of which there were many. His father spent most of Butts' childhood in prison and his mother, an intravenous-drug user, died of AIDS when he was 4. Butts was born HIV-positive, but he’d been among the first to receive in vitro treatments of the HIV inhibitor drug AZT, and 16 months later there was no trace of the virus in his body. Newspaper reports at the time suggested it was divine intervention, but what came next didn’t feel especially miraculous. Butts lived with his grandparents, who were kind and supportive, but when he was 12 they moved from the big city of Arlington near Dallas to Olney, Texas, population 3,300. Life in Olney was boring and lonely — until the day he and a few other kids first got high.

“We were running down the road, throwing sticks at each other, and everything was funny as hell,” said Butts. “It made everything better.”

Sitting in a shabby armchair at Posada, a homeless services center, Butts yawned as he remembered that moment. It was early on his second morning in Pueblo, before his job-hunting excursion to the mall, the sky outside bright and clear. Posada, Butts had decided, would be “crucial to my success,” his daytime base of operations, and he’d come here to take a shower before looking for work. He was still groggy, though, from both sleeping at the rescue mission the night before and the hits of a joint he’d been handed behind the shelter earlier that morning. “Thanks,” he’d told the guys sharing the smoke. “No, thank you,” they’d replied, as if he’d done something special by joining them.

When Butts boarded the bus in Texas, he’d been aiming for Colorado Springs, since he’d visited there once before. But when he’d heard in transit that Colorado Springs had banned recreational marijuana shops, he changed his destination to Pueblo, a community in the high desert plains someone on the bus had said was cannabis-friendly.

Pueblo, in fact, has become widely recognized for marijuana. Once the “Pittsburgh of the West,” Pueblo, population 108,000, had been looking for an economic springboard since its steel industry collapsed in the 1980s. County commissioners figured they might have found one when Colorado voted to legalize recreational marijuana in 2012, and they adopted some of the most marijuana-friendly business rules in the state. The area appears to be reaping the benefits: One-third of all new building permits in Pueblo County are related to cannabis, the unemployment rate has dropped more dramatically than in any other major Colorado metropolitan area and the county now boasts 1,300 licensed marijuana employees. And with $3 million in marijuana tax revenues generated over the past two years, the county has been granting college scholarships and building playgrounds with cannabis funds.

But Anne Stattelman, Posada’s director, pointed out that Pueblo still has the second-highest poverty rate in the state, a figure that’s growing. The number of homeless clients served by Posada doubled between 2013 and 2015, and Stattelman says shelters currently have enough beds for just 1 percent of the area's total homeless population. While Stattelman believes there are many reasons homeless people are flocking to Pueblo, she thinks one of the main motivations is the marijuana industry.

“We saw an increase on Jan. 2, 2014,” said Stattelman, referring to the day after Colorado launched its legal marijuana market. “And we have seen a steady increase since that time.” She’s become used to seeing her parking lot filled with vehicles from the South and the East Coast, their interiors overflowing with personal belongings. Families tell her they’ve come from places like Tennessee and Oklahoma because of marijuana, and they end up camping outside of town and using Posada for showers. “It looks like something out of ‘Grapes of Wrath,’” said Stattelman. According to Posada, 273 homeless households working with the center reported they’d come to Pueblo for legalized marijuana in 2015, up from 231 in 2014. That figure doesn’t include youth like Butts who utilize Posada, and Stattelman figures the total number of homeless drawn to the area because of cannabis could be much higher.

While overall U.S. homelessness decreased between 2013 and 2014 as the country moved out of the recession, Colorado was one of 17 states that saw homeless numbers increase during that time. And in Denver, whose metro area accounted for roughly 60 percent of the 10,000-plus Colorado homeless individuals in 2015, shelter usage grew from roughly 28,000 accommodations per month in July 2012 to 42,000 accommodations in November 2015.

Homelessness experts point out that there’s no proof that marijuana leads to homelessness, or that cannabis is the main culprit behind the growing numbers. Study after study has concluded that the major factors leading to homelessness are a lack of affordable housing, inability to find work and family crises. “There is very little safety when you are homeless,” said James Gillespie, community impact and government relations liaison for the Comitis Crisis Center, a shelter in Aurora, near Denver. “How many people want to trade their safety for access to something like marijuana or any other substance?”

But there is evidence that people who were already struggling to get by in other states are relocating to Colorado in part because of marijuana. So far, however, research on the phenomenon has been limited. A survey of Denver shelter workers by Metropolitan State University in the fall of 2014 found that eight of the 11 shelters said they were seeing client increases due in part to marijuana, said lead researcher Rebecca Trammell, but the study did not examine what, exactly those increases looked like. Plus some shelters actively avoid asking about marijuana use. “We certainly understand people are coming to Denver for marijuana, but we can’t make any claims on the direct impact on our program or shelter,” said the director of public relations at Denver Rescue Mission, the city’s largest shelter operator. “We see our Lawrence Street Community Center as a safe haven for people and a place where people can connect with needed services. For those reasons, we don’t often ask for a lot of information from people.”

But managers of many Colorado shelters say they’ve collected enough anecdotal evidence to estimate the number of marijuana migrants they’re seeing in their programs. At Denver’s St. Francis Center day shelter, executive director Tom Luehrs said a survey conducted by a grad student last year found that between 17 and 20 percent of the 350 or so new people the center was seeing each month said they’d come to the area in part because of medical marijuana. If anything, said Luehrs and his colleagues, that figure is low. At the nearby Salvation Army Crossroads Shelter, an informal survey of 500 newcomers in the summer of 2014 determined that nearly 30 percent were there because of cannabis. “Thirty percent is the number my staff tell me are coming for the marijuana industry,” said Lt. Col. Daniel L. Starrett, Intermountain divisional commander for the Salvation Army. “Not only has that number been sustained, but it has continued to grow.”

And at Urban Peak, a Denver shelter for people ages 15 to 24, CEO Kim Easton believes the figure might be higher for homeless kids. “For a while, we informally collected information, and at least one in three of the youth were saying said they were here in Denver because of the legalization of marijuana,” she said. “In the spring following legalization, we had a dramatic increase in the number of youth seeking services, a 150 percent increase just coming in the door. That has become our new normal.”

Representatives of homeless shelters and services in other nearby cities, such as Colorado Springs, say they’ve seen similar, albeit smaller, client upticks due to cannabis. But the phenomenon appears to be limited to Colorado. Representatives of shelters in Seattle and in Portland, Oregon, say they haven’t seen evidence that new clients are being drawn there because their states legalized cannabis. Nor have major shelters in San Francisco or Los Angeles seen much evidence of marijuana migrants, even though those cities are known for their robust medical marijuana markets.

It's unclear why only Colorado’s shelters are seeing such an impact from cannabis. Maybe thanks to all the attention the state has received for having the first and most mature legal marijuana industry, people associate cannabis with Colorado more than anywhere else. Or maybe, as the closest state to the East Coast and the South to have legalized marijuana, Colorado ends up being the first place to stop for folks like Butts who’ve set off to find a place where they can safely get high.

Numbing the Pain

Butts refused to panhandle to buy marijuana. “I’d rather make money legitimately,” he said. “If you are going to smoke, you should work and not run around begging for it.”

But in Pueblo, he found it was easy to score cannabis, even if you didn’t have much money to pay for it. After his job hunt at the Pueblo Mall, he headed back into town for lunch at the Pueblo Community Soup Kitchen, where he ran into a guy with a ponytail and goatee he’d met at the rescue mission the night before.

“What’s up, dude,” he said to Butts, flashing an orange plastic pill bottle containing a few nuggets of marijuana. “I have some Chemdawg, man.”

The two made their way down an alley behind the soup kitchen. Pulling rolling papers from his backpack, Butts kneeled against a chain-link fence and used his Bible as a work surface as he rolled a joint. “I love Colorado, man,” he said as his lit up the results.

“Want to buy the rest of that smoke?” asked the man.

“I only have a couple bucks,” said Butts.

“That’ll do,” he replied, handing over the pill bottle, as well as a small blue pill. It’s speed, the man said. On the house.

Butts slipped the pill into his pocket. He didn’t blame marijuana for the harder drugs he fell into as he got older; he said the court system, and what it did to him over pot, was his gateway into addiction. When he was 17, he was put on probation for getting caught with marijuana paraphernalia. That’s when he started getting hydrocodone pills from his neighbor, since the opioids were easier than cannabis to clear out of his system before his court-ordered drug tests. When the hydrocodone became too expensive, he moved on to meth.

Everything started falling apart. He spent nine months in jail for buying a dime bag of pot in a school zone, then another 10 months behind bars for using his grandfather’s checks to buy OxyContin. He had a son who is now in foster care and a daughter with another woman with whom he currently doesn’t have contact. For a while, living off and on the streets, he was hooked on crack. “Crack was a roller coaster,” he said. “I hated it.”

He got off the crack, but not the meth or marijuana. Last February, he was busted again, for having just over a half gram of marijuana while on probation. This is the other reason he’s here in Pueblo, the other reason he decided it was time for a clean start: A week earlier, his lawyer had told him the new marijuana charge was finally moving forward in the courts. He was looking at another 120 days behind bars. “I said, ‘F*** that,’” said Butts. He wasn’t going back to jail for cannabis.

Butts isn’t the only one coming to Colorado to use marijuana without the risk of getting arrested. “Some youth are coming to Colorado because it’s one less thing to worry about,” said Easton at Urban Peak. “They are going to use some sort of drug to numb the pain they have experienced in their lives. So they are going to use marijuana without the repercussions.”

But Easton worries that her clients still face serious repercussions for marijuana use. For starters, while marijuana’s potential health risks are hotly debated, there’s general agreement that it’s detrimental for developing brains, so she’s concerned about cannabis use among youth suffering homelessness. She also fears marijuana could be a contributing factor to the low enrollment she’s witnessed in Urban Peak’s education and job training programs. “We are seeing more youth who come in and have breakfast, take a hot shower, do their laundry, but aren’t motivated to get involved in programs that will help them change their circumstances,” she said. Finally, there’s the fact that legal marijuana’s high store price, thanks to various taxes, could lead some to opt for cheaper street drugs like heroin.

Plus individuals living in poverty in Colorado still risk being penalized for marijuana use. Many Colorado shelters forbid marijuana use or storage in their facilities, meaning some individuals might be staying away. And while marijuana might be legal for people over 21 in Colorado, public consumption of it isn’t, which means those without private residences have few options where they can use it legally. After Colorado launched its legal marijuana regime in 2014, citations for public marijuana consumption and display in Denver jumped to 762 from 184 in 2013, and arrests for marijuana use in parks climbed from zero to 248.

Circumstances like this have led Gary Darling, director of criminal justice services for Larimer County in northern Colorado, to believe marijuana might be why the number of homeless individuals in his jail went from 674 in 2012 to 1,018 in 2015. “The trend wasn’t that steep beforehand,” said Darling. “Why else would we be seeing that?”

There’s another way marijuana could be causing problems for those struggling to get by. Cannabis cultivation facilities proliferated in Denver starting in 2009, when the state's medical marijuana industry took off. Between then and 2014, grow operations were responsible for more than a third of all industrial space newly leased in Denver, leading to skyrocketing commercial real estate prices and very few vacancies. The state’s new marijuana market is also believed to be one of several factors behind Colorado having one of the fastest-growing housing markets in the country. In other words, cannabis might be in part responsible for dwindling affordable housing in Denver and beyond, which research has shown is the primary driver of homelessness.

“In my assessment, marijuana itself isn’t the issue,” said Cathy Alderman, vice president of communications and public policy for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. “The issue is Denver has a thriving economy and marijuana is part of that economy, but we don’t have enough housing for people, no matter what industry they want to participate in.”

Shifting Opinions

But aside from leading to an increase in shelter demand, most homeless shelter employees say legalized marijuana doesn’t seem to be harming their clients, nor is it increasing demand for their drug-rehab programs. In fact, many staffers say cannabis has benefited their clients, providing them relief from physical and psychological pain in ways that are safer and easier than both street drugs and expensive prescription pain meds.

At Denver’s St. Francis Center day shelter, Luehrs and his colleagues have been struck by the stories they’ve heard, like that of the Texas resident who left his home and family behind to see if legalized marijuana could help alleviate his debilitating chronic pain, and the Arkansas electrician who’d arrived in town without a job or place to live, but desperate to use cannabis for his depression. “My opinion has shifted in a big way,” said Luehrs. “People become homeless for a variety of reasons. It’s not just because they are addicted to drugs or alcohol. It’s because they had trauma in their lives, and this is a way to deal with that trauma.”

That’s what Butts aimed to do in Pueblo: use marijuana, and marijuana alone, to deal with the pain of his past. But he knew avoiding other forms of self-medication wouldn’t be easy. It’s why he planned to stick to himself in his new home, to avoid unnecessary temptation. And it’s why he wasn’t planning on using the blue pill he’d been given; he was going to sell it. “I’m not into that, but I can find someone who is,” he said after his hook-up behind the soup kitchen wandered away. “I’ll get my $2 back.”

A few minutes later, though, Butts pulled the pill out of his pocket. Maybe the lure of what he’d been given was too great — and there was still too much to do today, too much at stake, to be at the mercy of such temptation.

He looked at the pill long and hard, then threw it in the gutter.

This story continues tomorrow in “Marijuana Legalization: Pot Brings Poor People To Colorado, But What’s Being Done To Help Them?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.