Mars Planet Dust Storm Could Explain What Happened To Water On Red Planet

One of the greatest mysteries of the Planet Mars is the fact that the Red Planet was once covered with oceans of water billions of years ago. Today, Mars is a cold, dry and dusty planet with only water trails to give scientists clues that water once existed or could still exist.

New studies, however, suggest the largest dust storm in Mars could give a clue on how water disappeared in Mars. According to the New Scientist website, researchers used data gathered from last year’s largest recorded dust storm which circled the entire Martian globe to see how such a phenomenon could have contributed in the disappearance of water in Mars. The dust storm was so massive that it hid most of the planet’s surface from the sun which eventually “killed” the NASA rover, Opportunity, which relied on solar power.

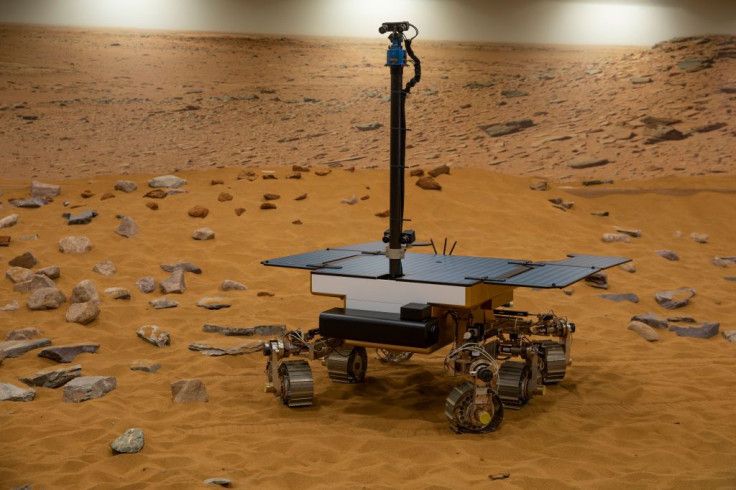

Using images and information caught by the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, scientists were able to examine how the dust storm not only absorbed sunlight but also affected the atmosphere. Ann Carine Vandaele at the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy and her colleagues made use of information gathered to see how water could have behaved during the storm.

Based on the study, they discovered that just before the cataclysmic storm, there were water ice clouds in the atmosphere but has no water vapor in the area that’s more than 40 kilometers above the surface. This, however, changed after a few days when water vapor appeared at altitudes of 40 and 80 kilometers, replacing the water ice clouds.

Because of this, dust probably absorbed the heat and warmed up the atmosphere which made it impossible to further form ice clouds. Based on the data, Vandaele and her team concluded that dust storms caused gases which include water vapor to escape into space, leaving Mars dry and eventually making it inhospitable.

“We are certain that in the past Mars was wetter and warmer, but we have to understand where the water went,” Vandaele said, pointing out that understanding the Red Planet’s atmospheric events could be a crucial first step.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.