Mystery Behind The ‘Pompeii’ Of China Solved? Jehol Biota Animals ‘Got Fried’ By Volcanic Ash [PHOTOS]

The thousands of well-preserved dinosaur, bird and early mammal fossils excavated from a famous archeological site in China most likely died from a series of volcanic eruptions that took place more than 120 million years ago, a new study suggests.

The fossils, which have been touted for their exceptional preservation and diversity, had long been known to researchers – but until recently the creatures' cause of death remained a mystery. Findings published in Nature Communications reveals that the ash entombed their bodies, preserving them much like the bodies found in Pompeii, National Geographic reports.

"What we're talking about in this case is literal charring, like somebody got put in the grill," George Harlow, a mineralogist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, one of the researchers of the study, told Live Science. "They got fried."

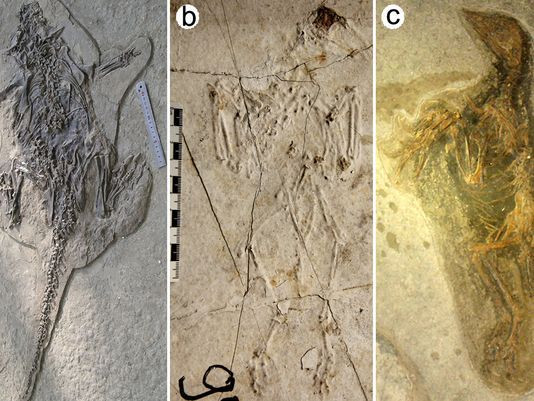

The fossils belonged to Jehol Biota, an ancient ecosystem that existed in northern China 120 million to 130 million years ago. Researchers used 14 fossils of birds and dinosaurs excavated from five locations around the site where they identified burnt tissue and "re-crystallized" sections of bone on fossils. According to Baoyu Jiang, a paleontologist at Nanjing University, these were clear signs the animals were exposed to extreme heat. The animals were also found with bent limbs, a common sign of being killed by pyroclastic flows — rivers of volcanic gas that can travel up to 50 miles per hour.

"That’s quite a radical, new idea," Mike Benton, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol in England, told NBC News in an email, and "quite a challenge" to previous theories that suggested the rivers carried animals into the lakes.

"All the evidence supports this hypothesis," said study co-author Jin Meng, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History. "Many or most of the vertebrate fossils were preserved this way."

A similar pyroclastic density was responsible for destroying the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 AD. As for the animal fossils, their positions are aligned with those from the skeletal remains found after the 1902 Mount Pelee eruptions. Some of the fossils showed darkening of bones, suggesting it is carbonized muscle and skin tissue from ash burning their bodies, the Smithsonian reports.

“The fine-grained volcanic ash that encloses the remains probably formed moulds around complete skeletons, resembling the intact, buried corpses at Pompeii,” the authors write. “The burnt, charred or mummified organic tissues probably served as templates for the extremely fine-grained ashes that coated them, forming the two- dimensional body outlines.”

Not everyone agrees with the latest findings.

"I'm not saying the authors are incorrect," University College Dublin geologist Patrick Orr, a specialist in the preservation of fossils, said, "but there are other plausible mechanisms (for such fossil preservation) that have been reported elsewhere. … Like all good, provocative papers, this challenges existing ideas and sets up a whole new set of questions."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.