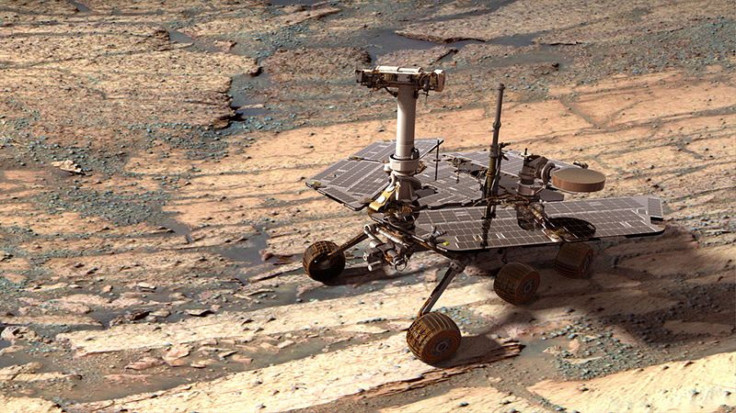

Opportunity Rover Embarks On 10th Year Of Exploring Mars

Even though it’s a federal holiday on Monday, at least one government employee will still be working: the NASA rover Opportunity. The little robot, about to start its 10th year of exploring on Mars, has already racked up some serious overtime – Opportunity’s mission has lasted more than eight years longer than originally planned.

This week marks the ninth anniversary of Opportunity’s touchdown on the Meridiani Planum, a flat plain close to the Martian equator. The landing site was selected because the plain has traces of hematite, a mineral that on Earth usually forms in standing pools of water or in hot springs.

Like its car-sized sibling Curiosity and its twin Spirit, Opportunity is chiefly looking for geological traces of ancient water on the Red Planet, and also for signs that conditions could have once supported life.

About six weeks after landing, Opportunity struck scientific gold, discovering rocks that had crystals tucked into niches and sulfates, evidence that they had been shaped partially by water.

“Liquid water once flowed through these rocks. It changed their texture, and it changed their chemistry," Cornell University scientist and Opportunity principal investigator Steve Squyres said in a 2004 statement.

In 2011, Opportunity also found a vein of what appears to be the mineral gypsum, which we use here on Earth to make drywall and Plaster of Paris.

"This tells a slam-dunk story that water flowed through underground fractures in the rock," Squyres said in a statement in 2011.

The rover also quickly stumbled across a curious rock feature: little spheres embedded in bedrock, like blueberries studding the surface of a muffin. The “blueberries” that Opportunity found are rich in iron, and about the size of peppercorns.

NASA scientists think the little spheres formed as water penetrated rocks. Blueberries that the robot found deeper underneath a crater’s surface are larger, which suggests the groundwater was flowing more intensely further below the surface.

Throughout the years, Opportunity has held up remarkably well, though the “shoulder” of its robotic arm has malfunctioned slightly and, like any aging creature, is experiencing some memory problems of late. It has weathered dust storms and frigid Martian winters, clocked more than 22 miles on its six wheels, and sent more than 100,000 pictures back to Earth. Though it lacks some of the more sophisticated instrumentation that Curiosity has, Opportunity can inspect samples with spectrometers and a microscopic camera.

This past December, Opportunity began scrutinizing Matijevic Hill, an area where Mars orbiters have picked up signs of clay minerals that form in wet, non-acidic conditions – an environment that is also favorable for the persistence of life.

It’s already found little spheres similar to the “blueberries” it found earlier, but these “newberries,” as investigator Squyres calls them, do not have that much iron. It’s still unclear exactly what they’re made of, or how they formed.

“What we have stumbled upon here at Matijevic Hill, drawn here by that clay signature, is what’s turning out to be one of the most delightful geologic puzzles that we have ever found with this rover on Mars,” Squyres told the New York Times in December. “It’s fascinating. It’s a work in progress.”

Both Spirit and Opportunity were only supposed to operate for about three months, but kept on trucking. Spirit got stuck in sand in 2010 and was lost to the Martian winter, but its sister robot is still carrying the fire.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.