Our 3-Million-Year-Old Ancestors' Children Were Walking, Climbing Trees

As scientists continue to explore the history of human evolution, a group of researchers found that some 3 million years ago, the children of our ancestors were able to stand on their feet, walk upright, and even climb trees.

Back in 2002, archaeologists discovered a nearly complete human skeleton, which turned out to be remains of a female toddler who lived in East Africa three and half million years ago but died before reaching the age of four. She belonged to the Australopithecus afarensis group of hominins, our distant relatives.

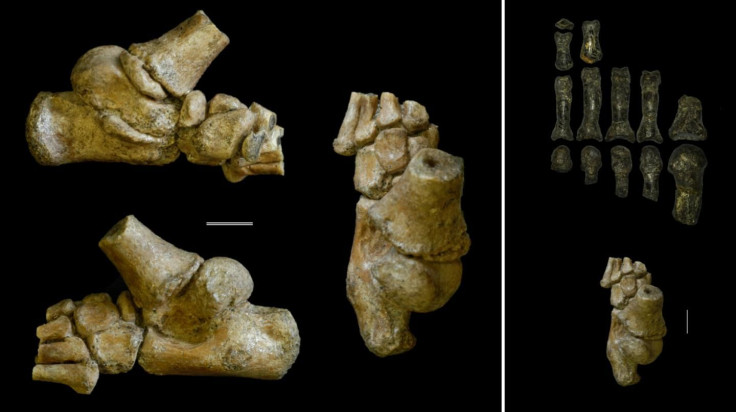

The analysis of that fossil provided crucial insight into the lives of our ancestors, but just recently, a group of researchers decided to focus on the tiny foot of the ancient skeleton in a bid to understand how their feet grew and were used.

Though it has already been established that A. afarensis adults were able to walk on two legs back in the day, not many studies have analyzed the anatomy of their children. This prompted Jeremy DeSilva from Dartmouth College and Zeresenay Alemseged, who discovered the fossil, to conduct the latest research.

“Every fossil gives us some bit of our past, [but] when you have a child skeleton, you can ask questions about growth and development—and what the life of a kid was like three million years ago,” DeSilva told National Geographic. “It's a magnificent find.”

The group took a close look at the rare toddler skeleton, named Selam, and noted signs of ape-like features on its foot. Essentially, the base joint of the subject’s big toe was curved, something that suggested she was able to wiggle the toe more than modern-day humans and use it for gripping. While previous researchers also found the curve in adults of the same species, the one noted here was much more pronounced.

This led the group to posit that groups of A. afarensis were able to climb trees, but their children did that more frequently. They think young members of the group would have used their well-gripping feet either to climb onto trees and avoid predators roaming around or to hold on to their mothers.

Meanwhile, adults of the group were using the foot features to climb trees only when it was time for them to sleep at a safe place, beyond the reach of predators. Such features are not seen in the toe joints of modern-day humans.

“For the first time, we have an amazing window into what walking was like for a 2½-year-old, more than 3 million years ago,” DeSilva said in a statement. “If you were living in Africa 3 million years ago without fire, without structures, and without any means of defense, you'd better be able to get up in a tree when the sun goes down.”

The finding improves our knowledge of hominin evolution and according to the researchers, further work could reveal more about their adult parents.

The study titled, “A nearly complete foot from Dikika, Ethiopia and its implications for the ontogeny and function of Australopithecus afarensis,” was published July 4 in the journal Science Advances.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.