Pandemic Poses Perfect Storm Scenario For Argentine Debt

In the midst of a delicate debt restructuring, Argentina is holding its breath as the coronavirus pandemic coupled with an oil price slump poses a perfect storm for its economy.

The omens are not encouraging for the leftist administration of President Alberto Fernandez, who has been battling global economic headwinds since taking office three months ago.

"The economy fell last year, surely this year it will fall too and I don't know, with all this international conflict, if it won't deepen the crisis," Fernandez said in an interview with Argentine radio last week.

"The world is conspiring to make our exit (from the crisis) more difficult."

Argentina has stumbled through a two-year recession with GDP down 2.1 percent in 2019, after a 2.5 percent fall the previous year.

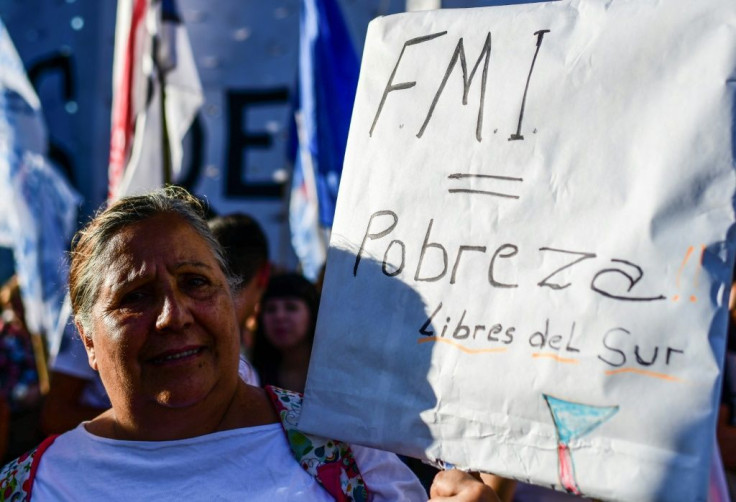

The International Monetary Fund forecasts a further contraction of 1.3 percent in 2020. In addition to rising poverty and unemployment, Buenos Aires is also grappling with inflation which soared to nearly 54 percent in 2019.

And the turmoil on the markets this week has roiled the government's restructuring deal with creditors.

Economy Minister Martin Guzman has met investors to try to finalize the restructuring of $69 billion of the country's massive public debt before a March 31 deadline.

The US-trained economist is also hoping to delay the maturity of some institutional loans.

Argentina currently owes $311 billion -- more than 90 percent of the country's GDP -- with more than $30 billion in repayments due before the end of March.

The overall debt includes $44 billion outstanding from a deeply unpopular $57 billion IMF bailout negotiated by Fernandez's center-right predecessor Mauricio Macri in 2018.

A default would block the grain exporter's access to global markets.

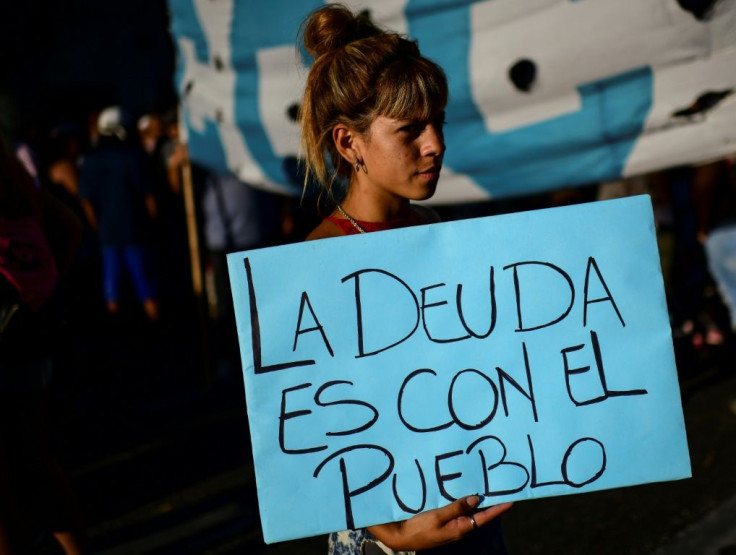

Setting the tone for tough negotiations with bondholders, Fernandez last month insisted the country will not be able to pay off its creditors if its recession-hit economy fails to resume growth.

He ruled out imposing austerity measures to help pay debt while poverty remains at record levels.

"The government wants to avoid a default but is also confident it can reach an agreement on its own terms" with bondholders, said market analyst Daniel Kerner of Eurasia.

Plunging global oil prices have raised fresh concerns over the viability of the government plan to exploit the huge Vaca Muerta shale reserves in Patagonia -- a cornerstone of Fernandez's plan to boost revenue.

Vaca Muerta's shale oil and gas deposit is considered among the world's largest.

Extraction began in 2013, but even with some 20 companies operating there -- including Chevron, Shell, Total and Statoil -- development has largely stalled, with barely 5 percent of the reserves being exploited, according to analyst Alejandro Einstoss.

As it stands, Vaca Muerta plays an important role in the domestic market, supplying three percent of the country's gas needs and 19 percent of its oil.

Production Minister Matias Kulfas has insisted that "the oil companies' interest in Vaca Muerta is still intact, despite the crisis."

But Einstoss of Argentina's Mosconi Energy Institute, says it would be illusory "to believe it represents a winning lottery ticket that will allow foreign currency to flow."

"Vaca Muerta is a potential that has yet to demonstrate its capacity in competitive markets," said Einstoss.

With oil now hovering as low as $30 a barrel and shale remaining expensive to exploit, the market is currently unfavorable to development of Vaca Muerta.

But Einstoss said that the drop in oil prices is unlikely to affect the reserves just yet.

"The industry is looking to the long-term. The big investment decisions are not made based on whether the price is $30 a barrel now or whether it was $70 in January," he said.

The global downturn, and the crisis caused by the coronavirus, could yet strangely benefit Argentina, according to economist Pablo Tigani.

"There is a violent deceleration in global economic activity. But I am optimistic about Argentina's debt restructuring because to do it while the world is in flames is not the same as doing it when the country is the only problem," he told AFP.

Given the new global scenario, Tigani foresees an extension in maturities of up to 10 years, capital withdrawals of 40 percent or more and a reduction in the interest rate of up to one percent.

"The terms will have to be stretched out no matter what if people can't even go out on the street," said Tigani. "The Federal Reserve is going to drop the rates if all bonds and securities lose ground. The take-off for Argentines has to be bigger than originally thought."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.