Pollen Levels On The Rise Thanks To Climate Change, Scientists Say

An unseasonably warm winter made 2012 one of the worst years for people with allergies, but scientists say it's just the start of an upward trend. Thanks to climate change, pollen counts are only going to climb higher, more than doubling by the year 2040.

Nearly 8 percent of people over the age of 18 in the U.S. have hay fever, or allergic rhinitis, which is primarily triggered by plant pollen. People with pollen allergies have immune systems that overreact to the presence of plant pollens and flood the body with inflammatory molecules, including histamines.

More pollen and longer pollen seasons will mean many more sniffly and itchy days for allergy sufferers. At a meeting for the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, allergist Leonard Bielory presented results from a study modeling climate change's predicted effect on pollen counts that is in progress at Rutgers University.

"Climate changes will increase pollen production considerably in the near future in different parts of the country," Bielory said in a statement Friday. "Economic growth, global environment sustainability, temperature and human-induced changes, such as increased levels of carbon dioxide, are all responsible for the influx that will continue to be seen."

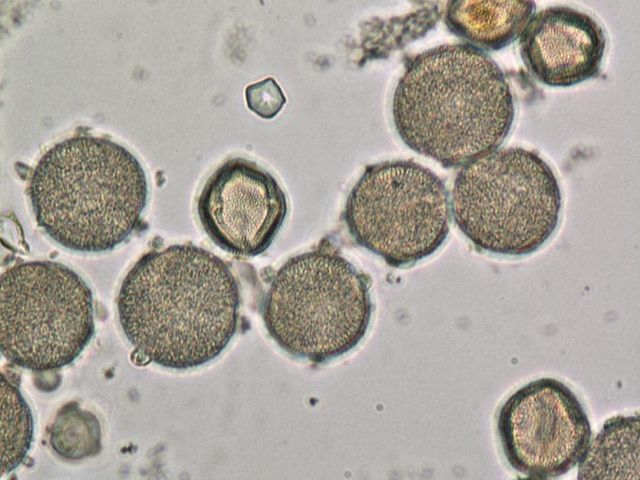

Pollen counts are measured by the number of grains of pollen in a cubic meter of air. The higher the count, the more pollen that's fluttering about, triggering allergies in sensitive people.

In 2000, the average pollen count was around 8,455. According to computer modeling and other experiments involving growing allergenic plants in specialized chambers, scientists expect this figure to rise to 21,735 by 2040.

"In 2000, annual pollen production began on April 14, and peaked on May 1," Bielory said. "Pollen levels are predicted to peak earlier on April 8, 2040. If allergy sufferers begin long-term treatment such as immunotherapy (allergy shots) now, they will have relief long before 2040 becomes a reality."

In February 2011, a team of researchers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Columbia University and other institutions connected climate change to a shift in flowering time and the initiation of pollen production. In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers reported that the length of the ragweed pollen season has been increasing in recent decades, increasing as frosts delayed and weakened at various latitudes.

Overall, the data shows that the ragweed pollen season has increased by between 13 and 27 days at latitudes above 44 degrees North – an area that includes the northernmost parts of the U.S. as well as all of Canada – since 1995. minneapolis has added 16 days to the ragweed pollen season, while Winnipeg in Canada has tacked on 25 days.

“If similar warming trends accompany long-term climate change," the researchers wrote, "greater exposure times to seasonal allergens may occur with subsequent effects on public health."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.