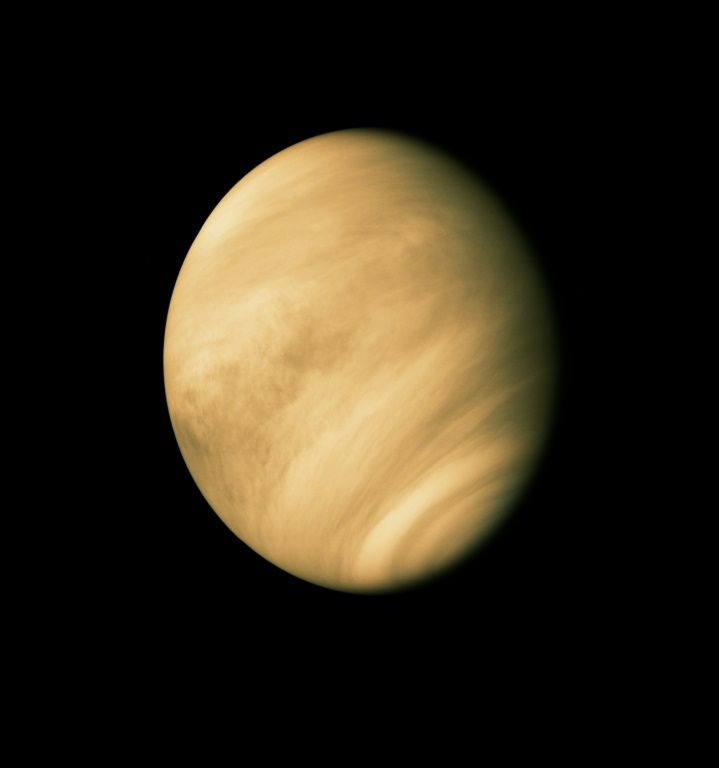

Probe's Natural Radio Signal Detection Suggests Changing Venus Atmosphere

KEY POINTS

- The Parker Solar Probe has an opportunity to study Venus with each flyby

- In its July 2020 flyby, it detected radio signals indicative of the planet's ionosphere

- The data from the flyby supports the theory about the planet's changing ionosphere

- It may shed light on why the Earth is so different from its "twin"

Scientists detected natural radio signals in the atmosphere of Venus during a recent spacecraft flyby, suggesting that it had passed through the planet's ionosphere. This could provide clues as to why the Earth and Venus are so different.

Although the Parker Solar Probe was not specifically designed to study Venus, it is using the planet's gravity to gradually get closer to the sun, NASA explained in a news release. And each time it passes, it also has an opportunity to study our neighbor.

In a new study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, a team of scientists describes the detection of natural radio signals when the spacecraft made its third flyby of Venus on July 11, 2020.

During this particular flyby, Parker Solar Probe made its closest approach to Venus yet, coming as close as 517 miles (833 kilometers) above its surface. During the few minutes when it was closest to the planet, its instruments detected a "natural, low-frequency radio signal" that Venus expert and lead scientist on the study, Glyn Collinson of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, eventually recognized as the planet's ionosphere based on previous work.

NASA shared a sonified version of the data that people can listen to.

Sound up! 🔉 NASA’s Parker Solar Probe discovered a natural radio signal in Venus’ upper atmosphere during its closest-ever flyby of the planet! The data — sonified here — is helping scientists study the atmosphere of Earth’s less hospitable twin: https://t.co/PaKZ4TV0iT pic.twitter.com/Z6JgR3QKGv

— NASA Goddard (@NASAGoddard) May 3, 2021

The ionosphere is an "electrically charged layer of gas" in the upper atmosphere, and it's something that the Earth also has. It turned out that the Parker Solar Probe flew through Venus' ionosphere during its recent flyby.

It provided the first direct measurement of Venus' atmosphere in almost 30 years, NASA said, noting that the last ones were taken in 1992 using the Pioneer Venus Orbiter. The findings may also shed light on why the neighboring planet is vastly different from ours.

Earth is so different from its 'twin'

Earth and Venus are essentially "twins," being quite similar in structure and size, NASA said. However, while the Earth is hospitable enough to host life, conditions on Venus have been described as "hellish," with its surface being hot enough to melt lead. Even the spacecraft that survived the longest on its surface, the USSR's Venera 13, lasted for just 127 minutes, the American Geophysical Union noted.

The belief is that the Earth's magnetic field plays a crucial role in its habitability as it protects the planet from losing its atmosphere, the researchers noted. Following this logic, Venus, which doesn't have a magnetic field, would then lose more of its atmosphere when the sun is more active.

"However, recent studies have shown the opposite to be true," the researchers wrote.

According to NASA, observations using ground-based telescopes suggested that Venus' ionosphere, which is located where gases can leak into space, is changing along with the solar cycle. Specifically, it appears that it is thinning when the sun is the least active.

Sure enough, the new data showed a much less dense ionosphere compared to previous measurements. The new measurements were taken just months after the solar minimum while previous measurements were taken close to the solar maximum.

"We were able to mathematically prove significant differences between this atmosphere and the one Pioneer saw many years ago," Collinson told Gizmodo in an interview.

As such, the findings do not only support the theory that Venus changes its ionosphere during the 11-year solar cycle, but they could also provide insights on why the Earth and its twin became so different.

"Understanding why Venus' ionosphere thins near solar minimum is one part of unraveling how Venus responds to the Sun — which will help researchers determine how Venus, once so similar to Earth, became the world of scorching, toxic air it is today," NASA said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.