Refugees In Libya: Europe Human Smuggling Military Solution Could Increase Death Toll Amid Crisis, Experts Say

One of the many consequences of the ongoing civil war in Libya has been the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of people from North Africa to Europe, often made possible by paying human smugglers to secure them spaces on dangerously packed boats heading to Italy or Greece. With nearly 3,000 people having drowned while attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea during 2015 alone, the European Union has been urged by the international community to take drastic action to stop the smugglers.

As a result, European leaders have embarked on a three-phase military mission that seeks to end a thriving human smuggling industry while simultaneously preventing people from drowning. But an aggressive approach, such as boarding vessels suspected of smuggling, removing the refugees and migrants, arresting the crew and impounding or sinking the boats once everyone has been removed, is unlikely to be effective as a long-term solution and will only make circumstances more dangerous for those looking to make the risky journey to Europe, people familiar with the situation said.

“Using the military to do this doesn’t guarantee an answer of how to stop these human smuggling groups," said Peter Roberts, Senior Research Fellow, Sea Power and Maritime Studies at the Royal United Services Institute, a London-based military think-tank. “The EU have not given any details behind how they would conduct the operation, no one understands how it’s going to happen. The entire operation seems like a knee jerk reaction and only for display to show that they are doing something.”

The instability of the war, which has been raging since May 2014, coupled with the country’s unsupervised ports, has facilitated sea departures for the more than 500,000 people desperate to escape conflict, unemployment, religious persecution and lack of opportunity as a means to attain a better future. Consequently, smugglers have commanded millions of dollars for their services to people who have made their way to Libya from various African countries, including Eritrea, the Central African Republic, Mali and northeastern Nigeria, according to a Washington Post report.

The first phase of the overall mission -- which is set to cost the EU around $11.8 million a year for an undetermined amount of time, with additional costs met by participating countries Italy, Germany and the U.K., began in July and was prompted by the death of 1,200 hundred refugees who drowned off the coast of Libya and Greece in early April -- focused on surveillance and assessment of the human smuggling networks in the Mediterranean. After the EU announced Monday that portion of the operation had ended, phase two, which includes searching and diverting the vessels, was launched. In phase three, which could take as long as a year to commence, military units are expected to travel into Libya to track down the smuggling rings and destroy their boats. However, the final phase would need a UN mandate to proceed as it would require international forces to enter a sovereign territory.

Only four ships have been committed to the mission so far: one British, one Italian and two German. But that number is not nearly enough to stop the smugglers, according to Roberts, who in July authored a report on the topic months in advance of the operation's start.

Ironically, the destruction of vessels used in the smuggling of humans either in the Mediterranean or Europe may actually increase the death toll, as it could “drive migrants to make crossings in unstable, inflatable boats” that “might make a successful crossing in calm seas, but not in harsher weather,” Roberts wrote in his report. Because Europe’s current naval forces were much smaller in fleet size than they used to be and would unlikely be able to monitor all of Libya’s coastline, “hard-line military activity to prevent migration into Europe across the Mediterranean could work: but it would involve killing migrants and enforced repatriation,” Roberts noted in the report.

In 2015 alone, around 250,000 refugees had arrived in Europe by sea, including 98,000 in Italy and 124,000 in Greece, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. A much higher estimate from the International Organization for Migration put the figure at more than 430,000 arriving by boat as of Sept. 10. Of those arriving in 2015, IOM said that 2,748 had died in the Mediterranean, of which 2,620 died coming across on the Central Mediterranean route from North Africa into Italy, which is a far longer and hazardous journey because of the rougher seas. Very few people have died on boats going across from Turkey into Greece, known as the eastern Mediterranean route. It's estimated by the International Policing group Interpol that approximately 30,000 people were taking part in the human smuggling rings at locations across the Middle East, Africa and Europe.

Since former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was ousted from power in 2011, human smuggling has gone from a niche business to a hugely profitable industry. Typically, each person is charged anywhere from $300 to $1,000, and small vessels with capacities of just a few dozen are loaded with more than 200 people at a time, according to a Guardian UK report. Smugglers specifically operating out of Libya stood to earn about $1 million weekly, providing the economic means for them to abandon ships and migrants at sea for any number of reasons, such as being confronted my legal authorities.

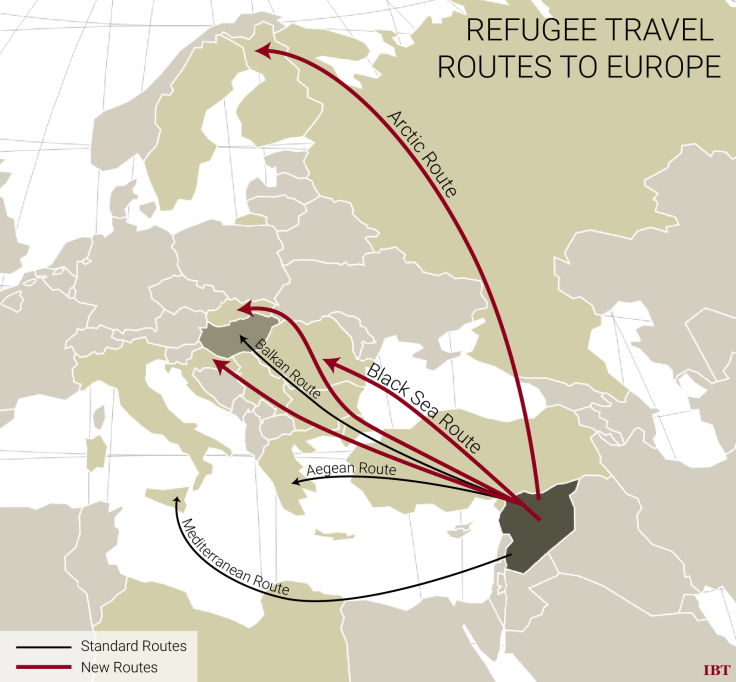

Traveling by sea has been established as the fastest way to get into Europe undetected, an aspect of the refugee crisis that smugglers have used to their advantage. Alternative routes do exist that would take people on foot or by car through the Middle East into Turkey and across to Europe are lengthy and fraught with danger because of conflicts in Syria and Iraq. Another option is traveling west toward Morocco, but that is also long and would only take travelers to the heavily guarded Strait of Gibraltar that leads to Spain. With no safe or legal routes to take, the most expedient route has proven to be the most popular, opening up lucrative opportunities for smugglers.

“Smugglers are flourishing because a market has been opened up to them by the fact there are no safe and legal routes into Europe, so a military operation isn’t the long term answer to this, and may not even be the short term solution,” said Gauri van Gulik, Deputy Europe Director at Amnesty International. “Europe is going to have to find alternatives to the dangerous routes that people are being forced to take.”

EU ministers have approved stepped up military action against Libya-based human smuggling networks, @AFP reports. https://t.co/nCsNJrQpZm

— Stratfor (@Stratfor) September 14, 2015The decision to move on to phase two comes after EU interior ministers met in Brussels Wednesday to work out how phase two of the EU mission would be conducted. Many EU member states, which must now work out what naval assets they are willing to contribute and what the rules of engagement will be when military forces board the smugglers boats, were reluctant to step up action against the smugglers for fear of getting embroiled in Libya where rival factions have been fighting for control since the ouster of Gaddafi.

While some countries in Europe such as Hungary and Germany have shut down their borders in an attempt to deal with the huge number of refugees coming in from North Africa and the Middle East, advocacy groups have complained that, much like the approach to deal with the human smuggling element of the crisis, sealing border crossings will not help the dire situation and that alternative solutions must be found.

“Ministers must abandon once and for all the Fortress Europe approach. Desperate people will keep coming and a coordinated emergency response coupled with an urgent overhaul of the EU’s approach to asylum can no longer wait.” said Iverna McGowan, Acting Director of Amnesty International's European Institutions Office.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.