Road To Rio: Brazil’s Middle-Class Dreams On Hold As Recession Hurts Households

Millions of middle-class Brazilians who’d hoped to marry, buy homes and start careers feel on hold as the country grapples with a recession. What comes next is anyone’s guess.

Humberto Cimino feels like his life is stuck in a holding pattern. The 24-year-old Brazilian would like to buy a nicer house in the sprawling megacity of São Paulo, a step he wants to take before he proposes to his girlfriend. But this seems like the worst possible time to reach for those major milestones.

As turmoil roils Brazil’s economy, Cimino said he worries he could lose his job in São Paulo’s emerging tech industry and end up buried under high-interest debt. And the turbulent housing market makes it difficult to know what's a good deal on a house, and what’s a bad bet. For now, he says, the best approach is wait-and-see.

“Who knows the future in this economy?” Cimino said on a video call from his office one recent afternoon, shaking his head. “We are having a lot of doubts about the outlook for the country.”

Cimino is among the more than 100 million Brazilians — over half the country’s population — who fall within the middle class. After growing for years, this demographic is starting to shrink as unemployment rises, inflation soars and wages diminish. Higher earners like Cimino are worried about their long-term prospects, while the millions of people on the lowest edge of the bracket risk falling back into poverty.

“Who knows the future in this economy?”

Brazil’s gloomy forecast stands in sharp contrast to the shining optimism that swept Latin America’s largest economy less than a decade ago.

The Brazilian economy was gaining strength in 2009 when beachfront Rio de Janeiro won its bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. A boost in foreign investment and a wave of infrastructure projects promised to create a wealth of jobs. Strong prices for commodity exports, such as iron ore and soybeans, allowed Brazil to withstand the worst of the 2008 global financial crisis. And social programs targeting impoverished Brazilians helped narrow the gaping canyon between rich and poor.

Today, less than four months from the Olympics' opening ceremony in August, Brazil is headed for its worst recession in nearly a century. The economy shrank by 3.8 percent in 2015 and is on pace to contract by another 3.8 percent this year, the International Monetary Fund estimated. Commodity prices are down, and business investment has stalled.

Economists say the Brazilian government has only made life harder for poor and middle-class citizens during the crisis by adopting austerity measures and raising taxes. Meanwhile, corruption scandals racking Brazil’s Congress and an ongoing bid to impeach President Dilma Rousseff have prevented leaders from repairing the nation’s chaotic economy.

Faced with such tumult, Brazil’s middle-class citizens are struggling to maintain their recent progress and protect their prospects for the future.

“There’s still a lot of open questions on what’s going to happen to all of these social gains that we saw over the last 10 years,” said Monica de Bolle, a Brazilian economist and senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, D.C. “The overall sentiment on the part of households continues to be very, very negative.”

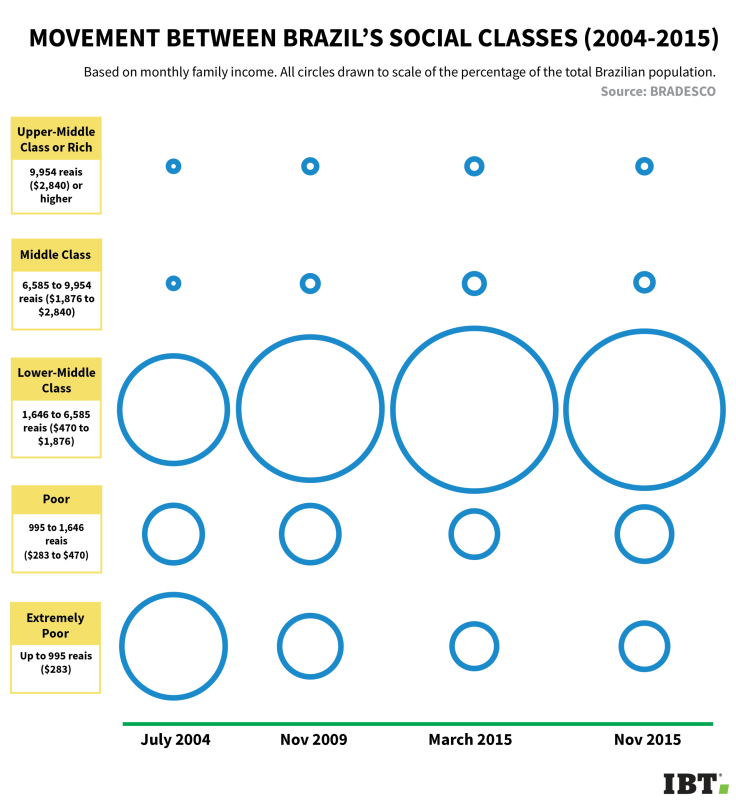

Brazilian families typically fall within one of five social classes. Class A includes the upper-middle class plus extremely wealthy Brazilians, while Class B includes the middle class. Class C, the largest social group by far, represents the lower-middle class. Poor citizens fall into Class D, and extremely poor Brazilians are considered Class E.

Over the past decade, the top three tiers (A, B and C) expanded while the bottom two classes (D and E) shrank, a sign of improving conditions for millions of Brazilians.

Graphic: Carla Astudillo / International Business Times

Average real wages jumped 34 percent from 2003 to 2014, helped by a more than 76 percent rise in the real minimum wage over the same period, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE in Portuguese) estimated. Bank loans and credit cards became much easier to secure, allowing families to upgrade their homes, buy new cars, take vacations and purchase other creature comforts that were previously out of reach.

More than 50 million Brazilians joined classes A, B and C between 2004 and 2014, growing those groups by about 63 percent, from nearly 80 million people to about 130 million, the Brazilian banking giant Banco Bradesco noted in a January report. Over that period, the country’s total population grew about 10 percent, from 184 million to 202 million people.

As Brazil’s economy sours, however, the opposite is starting to happen. Between January and November 2015, about 2.6 million people left social classes A and B, and another 3.7 million people left class C, the Bradesco report found. The lower classes D and E grew by a combined 6.5 million people as people exited the higher groups.

“The current economic scenario raises the question as to how sustainable the social mobility movement is,” the bank analysts wrote.

Bradesco pointed to two key reasons for Brazil’s shrinking middle class: higher unemployment rates and a decline in real wages.

Urban unemployment rose to 8.2 percent on average in February 2016, up 42 percent from the 5.8 percent rate a year ago, the IBGE statistics agency said in its most recent survey. Economists expect the rate to exceed 10 percent later this year. Meanwhile, inflation is just below 10 percent, pushing up the price of grocery store staples like meat and fresh vegetables and diminishing any gains in earnings.

Cimino said he feels lucky to have a well-paying job in São Paulo, where he works as a business analyst for the mobile ad network RevMob. Many of his 20-something peers are struggling to find work or land internships as more people compete for a narrowing pool of positions. “Now it’s almost impossible for people who are getting out of college to get jobs,” he said.

His girlfriend, who is a Russian citizen, was recently laid off from her banking job amid cutbacks and has yet to find another position open to foreign residents. Cimino’s father, who runs a handful of small companies, including a restaurant and a shooting range, was forced to trim his workforce of around 100 people to just 20 workers and slash wages to keep the businesses afloat. Cimino said his brother's internship with the French luxury retailer Hermès in São Paulo was recently canceled. The company said in an email that it is not retreating from the Brazilian market. But sales of luxury goods in general have slowed over the last year as consumers grow more cautious with their spending, Euromonitor International said.

Retail sales on the whole dropped 5.3 percent in the 12 months through February 2016 as the recession boosted unemployment and sent consumer confidence to record lows, IBGE reported earlier this month. The figures include supermarket items, furniture, clothing and other consumer goods but exclude cars and building materials.

The lack of jobs in Brazil has hit lower-middle-class residents particularly hard. Lower-skilled and less-educated workers have struggled more to secure stable, formal work compared to their higher-educated, higher-earning peers. Employers are also less likely to dismiss specialized workers, since companies may have invested in their training or need people with years of experience, the Bradesco analysts wrote in the January report.

“The people who over the last 10 years were able to access middle-class status because of the way the labor markets were behaving — these are the most vulnerable,” de Bolle said.

With fewer job prospects and higher consumer prices, Brazilians are having trouble paying off the debt they took on when Brazil was booming. Millions of new entrants to the middle class paid for new rooftops, appliances and furniture by taking out high-interest loans or participating in installment plans at retail and electronics stores. Other Brazilians racked up credit card debt or took out large bank loans as luxury clothing brands and global automakers set up shop in the South American nation.

Thanks to Brazil’s sky-high interest rates, Brazilian households now spend about 20 to 22 percent of their monthly disposable income to service their debts, up from 15 to 18 percent in 2006, according to central bank data. In the United States, by comparison, the ratio of debt service payments to household income was about 5.5 percent in the fourth quarter of last year.

Around 41 percent of Brazilian adults, or 60 million people, are behind on their debt payments, the credit bureau Serasa-Experian recently reported. That’s the highest number since the bureau started compiling delinquency data, in January 2012.

“A lot of the middle class was carrying a lot of debt, and if they lost their jobs, they now find themselves in a very tough position in a very tough environment,” de Bolle said.

Despite the turmoil, not all members of Brazil’s middle class — particularly the families on the higher end of the income bracket — have had to change their lifestyle.

Raphael Prado, a 32-year-old journalist, said bars and restaurants in São Paulo’s middle-class neighborhoods remain packed on evenings and weekends. He noted a Rolling Stones concert in the city in February saw thousands of Brazilians cram into the Morumbi Stadium.

“We’re still drinking our beers on a Friday night, traveling on weekends,” said Prado, who considers himself to be middle class. For many people in his peer group, the barrage of negative news and prevailing pessimism can feel worse than the actual effects of the recession, which tend to affect the poorest Brazilians the most.

“I guess what's worse than a crisis itself is the feeling of living under a crisis,” he said.

Corruption scandals snaking throughout Brazil’s political system have only further darkened the public mood, Prado added. The country is facing its deepest political crisis in decades, with many members of Congress accused of bribery and money laundering, and with Rousseff facing calls for her ouster.

Rousseff is accused of improperly using money from giant public banks to cover budget shortfalls, although she hasn’t been charged with any crime. Her impeachment proceedings could come to a head within a few weeks, which might bring some near-term relief for Brazil’s beleaguered middle class.

Members of Brazil’s lower house of Congress voted April 17 to impeach Rousseff. If the Senate agrees to consider the impeachment motion, which it will likely do in May, Rousseff will be forced to step aside for 180 days and could be ousted permanently.

Vice President Michel Temer would then become the interim president, although he, too, is facing scrutiny over claims he was involved in an illegal ethanol purchasing scheme. Temer has promised to appoint a team of experienced economists and money managers to stabilize the Brazilian economy and stem the fiscal blood loss.

De Bolle, the Brazilian economist, said the prospects for Brazil’s middle class and poorer residents could improve under a new administration, given that policymakers have refused to work with Rousseff and her Workers’ Party to adopt broad fiscal reforms.

“Even if it doesn’t improve immediately, at least the kind of hemorrhaging you’ve been seeing so far is likely to diminish and at some point stop,” she said. If the process to impeach Rousseff fails, she added, “There would be an even deeper economic crisis in Brazil if she stays in power. We would have an unambiguously bad scenario for the country and the middle class, and for the lower-middle class in particular.”

The Summer Olympics in Rio are similarly mired in corruption allegations, a point that has angered many Brazilians who are already frustrated by the government’s investment in the games, given the state of the economy.

When Brazil first landed the Olympics and the 2014 World Cup, both sporting events were billed as an opportunity to repair Brazil’s crumbling infrastructure, expand airports, improve public transportation and revitalize downtown areas. But many projects associated with the events faced significant delays and steep cost overruns, or remain uncompleted, reflecting the broader disarray plaguing Brazilian leadership. Part of an elevated bike lane built for the Olympics collapsed April 21 in an accident near the beachfront in Rio, killing two people.

The Olympic Games are expected to cost 39 billion reais ($11 billion), Brazil’s Olympic Public Authority said in January. That’s slightly less than the $12.8 billion that London spent to host the 2012 Summer Olympics and dramatically lower than the $40 billion tab for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

The Brazilian government will cover about 40 percent — or 15.6 billion reais — of the total cost for the Rio games, authorities said. Private companies will pay the rest, a group that includes five engineering firms responsible for building most of the venues and infrastructure needed for the Olympics.

“It’s almost impossible for people who are getting out of college to get jobs.”

All five firms are under investigation by Brazilian prosecutors for siphoning kickbacks from state oil firm Petrobras to political parties. The sweeping investigation includes Porto Maravilha (the “Marvelous Port”), a revitalization of Rio’s waterfront, as well as other infrastructure projects connected to the Olympics that have not yet been made public, Reuters reported April 19.

Back in São Paulo, Cimino said he’s not necessarily upset that Brazil is hosting the Olympics this summer. “We want the Olympics. We think it is very good and important, and we love to have foreign people here,” he said.

But Cimino is angry that the Brazilian government seems to have bungled the opportunity to stimulate the economy and complete major projects — such as an expanded subway system and high-speed rail link between major cities — that would benefit those on the middle and lower rungs of the economic ladder.

“We’re just really tired of everything, and everything related to government,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.