Saudi Arabia Defends Public Beheadings After ISIS Comparisons

While ISIS militants have made headlines for their brutal public executions of civilians, key Western ally Saudi Arabia has continued and even expanded its own policy of public beheadings with far less scrutiny. Despite protests Monday from a top Saudi official about comparisons between the Saudi government and ISIS, Saudi Arabia’s system of crime and punishment is remarkably similar to that of the Islamist organization it has denounced, experts said.

Both ISIS and Saudi Arabia’s absolute monarchy rely on the same ideology and system of religious interpretation in their approach to punishment, said Ali Al-Ahmed, a Saudi expert and the director of the Institute for Gulf Affairs in Washington, D.C. “The Saudi judicial process, if we can call it that, is the same as ISIS',” he said. Unlike every other Muslim country, Saudi Arabia refuses to codify its laws, which “gives the judge, or the government here because they are one and the same, leeway to decide whatever punishment they want.”

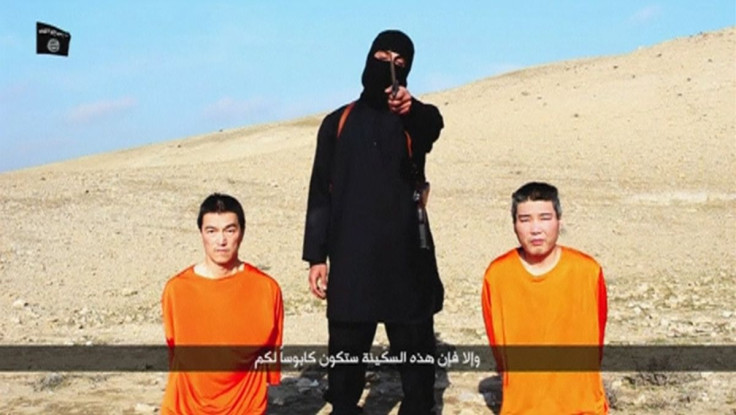

This, according to Al-Ahmed, is precisely the same system used by ISIS, which regularly hands down severe punishments in the territories under its control. The militant group, which rose to international prominence after capturing swaths of land in Iraq and Syria last year, has drawn outrage for its brutal tactics, including videotaped beheadings of journalists and other civilians.

Such a comparison was rejected by Interior Ministry spokesman Mansour al-Turki, who told NBC News in an interview published Monday that Saudi criminal punishments were legitimate because they were based on "a decision made by a court" rather than ISIS' "arbitrary" killings. "ISIS has no legitimate way to decide to kill people," he said, adding that "the difference is clear."

Human rights activists beg to differ, however. “It is not legitimate for Saudi Arabia to uphold the claim that there is due process rights within the proceedings of the judiciary,” said Fadi Al-Qadi, a Middle East spokesman for Human Rights Watch. According to the rights group, the kingdom executed at least 68 people last year for crimes such as murder, rape and drug trafficking. On Sunday, authorities beheaded a convicted murderer, bringing to 17 the number of people who have been executed since the beginning of 2015, reported Agence France-Presse.

Capital punishment is imposed in the kingdom under many problematic circumstances, said Delphine Lourtau, the lead researcher for the Death Penalty Worldwide project at Cornell Law School in Ithaca, New York. Not only are defendants often denied access to lawyers, but death sentences are often imposed in cases where confessions are obtained under torture, a circumstance that makes it impossible to justify the death penalty, she said. “Frequently, capital punishment is carried out for nonviolent offenses -- drug offenses that don't cause harm to anyone. These are particularly egregious violations of international law.”

Along with human rights groups, the United Nations has focused its scrutiny on the kingdom, particularly after it increased its rate of executions to one per day back in August, reported NBC. The U.N. said the kingdom’s practice of beheading citizens was “prohibited under international law under all circumstances” and said the government was carrying out executions "with appalling regularity and in flagrant disregard of international law standards."

The Saudi government’s beheading of a woman in Mecca on Jan. 12 has renewed attention on the issue after a video of the execution was posted online and distributed by human rights activists, according to the New York Times. The kingdom, which is part of the U.S.-led international coalition fighting the militant group, has not welcomed the spotlight on its beheading practices and has arrested the man thought to be responsible for shooting and publishing the video. Al-Turki’s comments on the issue follow weeks of unflattering comparisons between the Saudi government and ISIS on social media.

Despite al-Turki’s defensiveness on the subject, it is unlikely that Riyadh is feeling any significant international pressure to reform its justice system, said Al-Qadi. “The bottom line is you're not seeing a political, legal discussion about this among the Saudi elite,” he said. “Saudi Arabia’s allies in the West have to deliver a clear message that the battle against ISIS brings with it a commitment to human rights and a commitment on behalf of those participating in the coalition to bring an improvement to its own human rights record.”

Western governments have been notably silent on Saudi Arabia’s rights record, according to Lourtau, who pointed to deep ties between Riyadh, the U.S. and the European Union. In the case of the United States, which has been criticized for its own high rate of executions -- including botched attempts that have been described as inhumane -- it may also be difficult to credibly criticize the Saudis for their practice of capital punishment.

However, this should not deter Washington from pressing for reforms to the systemic problems underlying the practice and pushing for transparency, access to legal counsel and a stop to torture in prisons, said Lourtau. “These are all norms the U.S. can get behind and put pressure on its allies to enforce,” she said. “There is space for pressure and diplomatic negotiation even for countries that support capital punishment.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.