Scientist Explains How Observatories Will Detect Signs Of Alien Life In Exoplanets

KEY POINTS

- New observatories can measure an exoplanet's biosignature

- Biosignatures can help determine the presence of life in exoplanets

- The James Webb Space Telescope will be used to find habitable exoplanets

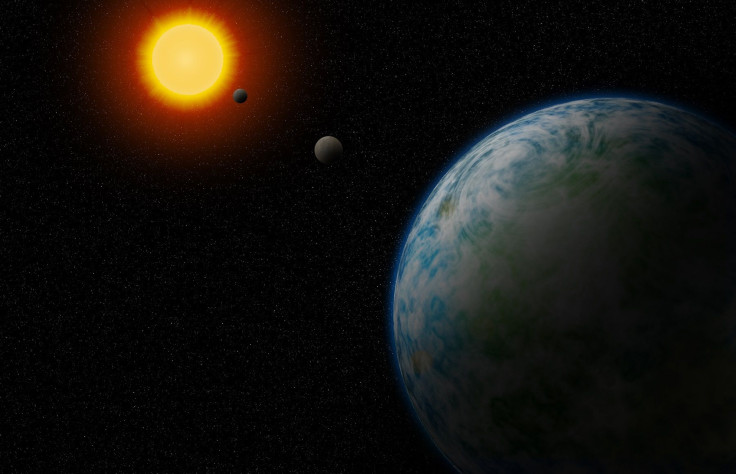

A scientist explained how new observatories, such as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, can measure the habitability of exoplanets by analyzing the biosignatures of their atmospheres. This information could be used to determine if a planet contains alien life.

The habitability of exoplanets, which are worlds beyond the Solar System, is usually determined by their distance from their host star. Planets that are not too far or too near from their host star could mean they have the right atmospheric and environmental conditions to support life.

Aside from an exoplanet’s proximity from its host star, a world’s potential habitability can also be determined through its biosignature. Biosignatures are chemical traces in the atmosphere that serve as telltale signs regarding an exoplanet’s environmental conditions.

For example, Earth’s atmosphere is composed of 21% oxygen. This biosignature is attributed to the oxygen produced by the planet’s plant life through photosynthesis. According to Victoria Meadows, an exoplanet researcher from the University of Washington, detecting biosignatures will play a crucial role in the missions of new observatories.

As noted by Meadows, one of the biosignatures that space and ground-based telescopes will look for is carbon dioxide. Although CO2 is not technically a biosignature on its own, Meadows said finding carbon dioxide existing with another chemical in the atmosphere could indicate that an exoplanet contains life.

“Both Venus and Mars have atmospheres with high levels of CO2, but no life,” Meadows said during an interview. “Instead [the James Webb Space Telescope] can look for another potential biosignature, methane gas in the presence of CO2. Methane should normally have a short lifetime with CO2.”

“So if we detect both together, something is probably actively producing methane. On Earth, most of the methane in our atmosphere is produced by life,” she continued.

According to Meadows, laboratories operating the new observatories have already identified the exoplanets that they will analyze. Many of these are about 40 light-years from Earth and orbit small stars. Some of the exoplanets that will be included in the observations are those orbiting a cool red dwarf star known as TRAPPIST-1.

“We’ve identified TRAPPIST-1 as the best system to study because this star is so small that we can get fairly large and informative signals off of the atmospheres of these worlds,” Meadows stated. “These are all cousins to Earth, but with a very different parent star, so it will be very interesting to see what their atmospheres are like.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.