Scientists Create Toxin Secreting Stem Cells To Fight Brain Tumors

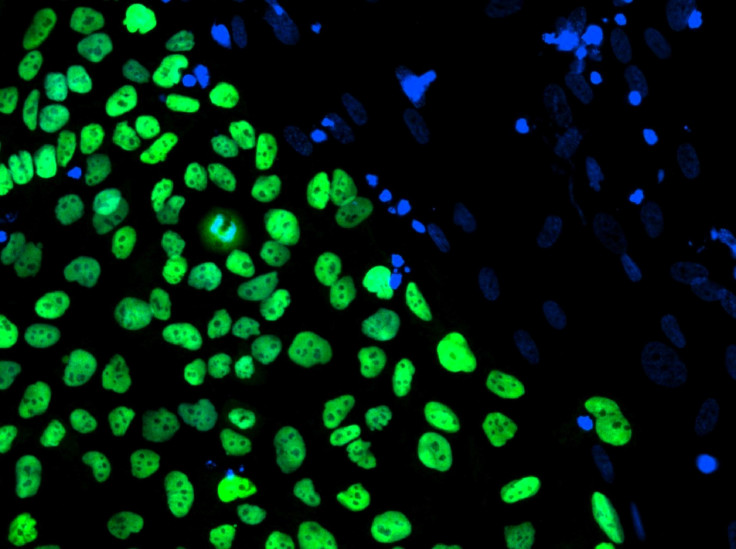

A team of Harvard Stem Cell Institute researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital has successfully engineered stem cells to produce toxins that can kill cancerous cells, turning them into lethal weapons to in the war against brain tumors. Their study was published online in the journal Stem Cells Friday.

For years, scientists have attempted to create cells that would not only kill cancerous cells but also do it without harming themselves or surrounding healthy cells. The genetically engineered stem cells created by the researchers in Boston were reportedly able to do so, making the development a potential milestone in the field of cancer treatment.

“Now, we have toxin-resistant stem cells that can make and release cancer-killing drugs,” Khalid Shah, a co-author of the study and the director of the molecular neurotherapy and imaging lab at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, said in a statement. “Cancer-killing toxins have been used with great success in a variety of blood cancers, but they don’t work as well in solid tumors because the cancers aren’t as accessible and the toxins have a short half-life.”

Based on experiments conducted on mice, the results were very positive, Shah said. “After doing all of the molecular analysis and imaging to track the inhibition of protein synthesis within brain tumors, we do see the toxins kill the cancer cells,” he said.

Chris Mason, a professor of regenerative medicine at University College London who was not involved in the research, hailed the findings as representative of “the future” of cancer treatment. “This is a clever study, which signals the beginning of the next wave of therapies,” Mason told BBC News. “It shows you can attack solid tumors by putting minipharmacies inside the patient which deliver the toxic payload direct to the tumor.”

However, Nell Barrie, the senior science information manager for Cancer Research UK, told BBC News that much more work is needed to see whether the treatment works on humans. Nonetheless, she said, “We urgently need better treatments for brain tumors, and this could help direct treatment to exactly where it’s needed.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.