Scientists Now Able to Predict Sunspots Days Before Solar Eruptions

Scientists have found a way to spot active regions of the sun, a full day or two before they erupt as sunspots, by listening to sound waves from deep inside the sun.

This prediction could possibly lead to better forecasts of dangerous solar storms, a new study said.

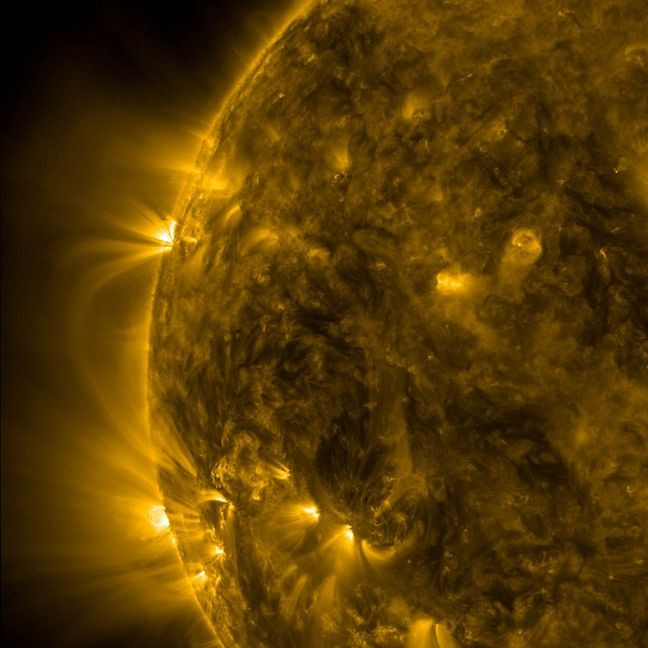

Sunspots are temporary dark splotches on the sun. They have strong, concentrated magnetic fields. Other magnetically-driven solar events like solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) tend to erupt from areas where sunspots appear.

Sunspots remained a mystery until a team of astronomers developed a new technique for detecting regions deep within the sun before they were visible on the surface. This new technique measures acoustic waves beneath the sun's surface.

It's the first time that we could detect sunspots before they appear at the surface — this is something that we could not do before, Stathis Ilonidis, a Ph.D. student at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif., and lead author of the study, told Space.com. It's very important to monitor solar activity and predict severe space weather events and we believe this work will be important for space weather forecasts.

Solar flares and CMEs that are aimed at Earth send clouds of charged particles from the sun that rush toward the planet. When these particles interact with the Earth's magnetic field, they create geomagnetic storms that can become a problem for astronauts and spacecraft in orbit. They can also pose hazards to power grids and telecommunications equipment on the ground.

If scientists can know when and where sunspots, solar flares and CMEs, will form, that just night be the key aspect of predicting solar storms.

The scientists found that sunspots that ultimately become large rise up to the surface quicker than those that stay small. The larger sunspots are the ones that spawn the biggest disruptions, and for those the warning time is roughly a day. The smaller ones can be found up to two days before they reach the surface, a new release stated.

With our technique, we can detect sunspot regions 60,000 kilometers [37,282 miles] below the [sun's] surface, and this gives us one to two days heads-up before they appear on the solar disc, Ilonidis told National Geographic. Up to now, sunspot regions could not be anticipated in advance, so we hope that our results will improve space-weather forecasts.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.