In The Streets: Argentina's Homeless Talk About Economic Crisis

The streets of Buenos Aires offer a glimpse at how the worst economic crisis to hit Argentina in nearly two decades -- a major issue in Sunday's presidential election -- is affecting everyday people.

More and more people are being forced to eke out an existence in public squares or train stations, perched on blankets or under cardboard boxes.

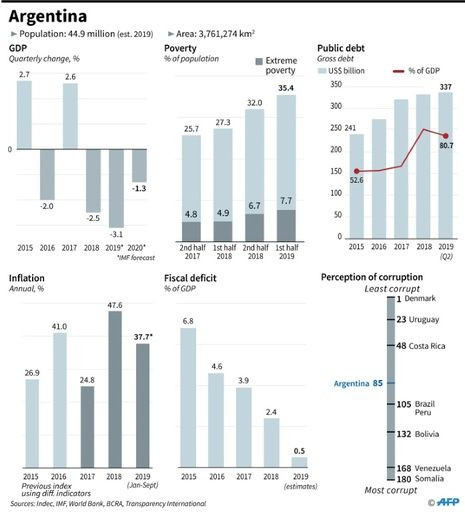

Since last year, inflation has soared in Argentina, unemployment is up and the poverty rate has skyrocketed to more than 35 percent.

In July, at the start of the South American country's winter, city officials in Buenos Aires had counted more than 1,100 people living rough.

But that same month, civic groups put the number at more than 7,200, citing official data -- and said more than half of them were homeless for the first time in their lives.

AFP talked to a few of them. Here are their stories:

'I eat if I'm given something'

Soledad Sanchez is a mother of seven children aged two to 19. At 36, she is already a grandmother. She lives near the famed Teatro Colon opera house in Buenos Aires -- but her life is nothing like its gilded halls.

By day, she sits in front of a supermarket. At night, she tries to sleep in an enclosure housing a bank ATM.

"I eat if I'm given something. If I don't get anything, I don't eat," Sanchez says.

Until February 2018, the salary of her husband -- a trash sorter -- combined with public assistance allowed the family to pay for lodging.

When they lost their benefits, her husband took his own life.

"He killed himself because of the situation we found ourselves in. They were threatening to take our kids away if we did not leave our hotel room. So one Friday, at 3 pm, he set himself on fire," she says.

"Before that, I had enough to get by, to put a roof over my children's heads. I could bathe them and feed them. How we live now, this isn't a life," she adds, cradling her six-year-old daughter.

The little girl no longer goes to school -- her supplies were stolen. Sanchez's other daughter, who is 15 and disabled, sits on the corner nearby.

The other children, Sanchez says with pride, are at school: "I send them to school so that someday they can be someone -- not like me."

'Despair'

Four years ago, 37-year-old Jose Rivero arrived in Argentina's capital from Salta province in the north.

He didn't have formal work, but he says he has always managed "to create a job when there wasn't one."

Just three months ago, Rivero was recycling items collected at a market to scrape by. But now, he wanders around all day. At night he sleeps in a homeless shelter.

"I have nothing left," he says.

Some days, he earns about $3 selling coffee and sandwiches outside a hospital.

"You can feel a lot of despair in the streets," Rivero says. Despite everything, he still has dreams.

"I came here from Salta hoping to pick myself up. For now, I won't admit defeat."

Cold, hard reality

After more than a decade of being homeless, 60-year-old painter Francisco Niubo has given up hope.

"It's time to accept this crappy reality, and no longer dream of things that one can't have," he says.

During daylight hours, Niubo walks around the city with a case containing his brushes and paints.

He hopes to find work decorating a store window or making a sign -- but it's rare.

"Five years ago, if you didn't get invited for a coffee, you at least got a soda, beer or a sandwich. Now, people don't have anything to eat, so they are less likely to offer me work to do," Niubo says.

"Before, we used to say, 'God help me' but now, it's like He took a vacation, because we are all starving."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.