The Sun Will Devour Mercury And Venus In 5 Billion Years; Will Earth Survive?

KEY POINTS

- The phenomenon is not unusual in a star's life cycle

- Researchers call these sun-like stars "cannibal stars"

- Studying them might help unlock some mysteries in astronomy

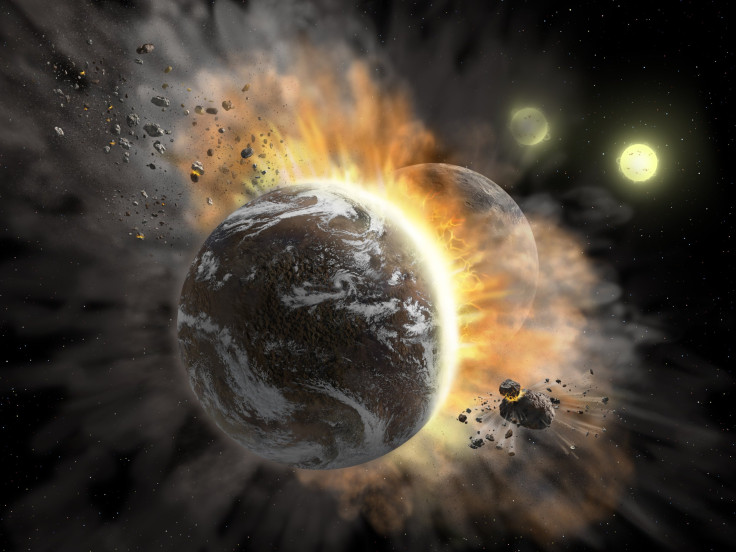

Our sun, the celestial body that sustains life on earth, will not always be so gracious. It will turn into a planet-eating monster and engulf Mercury and Venus in the next 5 billion years.

Perhaps the most important question that comes to one's mind in connection with this phenomenon is: What will be the fate of the Earth when this finally occurs? To provide possible answers to this burning question, a study published in the Astrophysical Journal focused on the said planetary engulfment.

"For the case of the Earth, I think it's rather unclear whether it's going to be engulfed or not, but it's certainly going to become impossible to live on," study co-author Ricardo Yarza, who is a graduate student in astronomy at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said, as per The New York Times. "It's always interesting to imagine a civilization becoming aware of this, like us, and realizing that at some point, you've got to leave home."

In five billion years, the sun will swallow Mercury, Venus and, possibly, Earth.

— The New York Times (@nytimes) August 20, 2022

Learning more about worlds that get engulfed by their stars may help us understand the long-term fate of Earth and provide clues in the search for extraterrestrial life.https://t.co/CZt6K1arKI

This phenomenon is not unusual in stars' life cycles. In fact, researchers call these sun-like stars "cannibal stars," although they actually swallow planets instead of other stars, and studying them as well as planetary engulfment might explain some mysteries in astronomy that have baffled scientists for years.

However, there is a more basic appeal to studying planetary engulfment — it may help us understand the very long-term fate of Earth and provide hints in the search for extraterrestrial life.

When these sun-like stars run out of hydrogen as they near their end, they expand their borders hundreds of times over and become red giants. Within this "red giant" phase, it is customary for stars to devour their innermost planets before draining whatever fuel they have left.

Another observation from the research is that stars enrich themselves with planetary elements like lithium in the process of engulfment, which leaves behind chemical signatures that can help astronomers identify cannibal stars.

"Catching the star engulfing a planet is going to be difficult to do" as it is "a short-lived event," study co-author Melinda Soares-Furtado, a NASA Hubble Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said about the phenomenon, according to the outlet.

"But the signatures that are left behind can be observable for much, much longer — even billions of years," she added.

This tricky nature of catching stars as they engulf planets is why there are many gaps in the current astronomical literature. Even creating models of engulfment events is challenging, and the huge disparities between the sizes of stars and their planetary meals are partly to blame.

"Understanding planetary engulfment and how it affects the fates of planetary systems involves answering several questions," Yarza explained, as per the outlet. "What happens to planets that are engulfed? Do some of them survive? Are all of them going to be destroyed? What happens to the star as a result of engulfment?"

In their study, however, Yarza and his colleagues managed to create models of engulfments of planets that are larger than Jupiter. To account for the size disparity of stars and planets, the scientists developed an approach that focussed on the gassy outer region of the star where planets are first engulfed.

Their findings suggest that stars with massive planets may take on more than they can handle, which results in extreme consequences for both objects. On the other hand, Earth-sized worlds are devoured much more easily.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.