Supermassive Black Holes In The Early Universe Likely Grew In ‘Fits And Spurts’

Supermassive black holes, found in the centers of almost all known galaxies, have masses that are several hundreds of thousands, even billions, of times more than the sun. And to accrete that much mass, the black holes would need that much material, and the time to consume it all. Which is why astrophysicists struggle to explain how the early universe, barely one billion years after the Big Bang, already contained supermassive black holes.

An all-female team of Italian researchers offered a new explanation in a paper recently published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. According to them, the earliest black holes fed on stellar material in fits and spurts, making their growth difficult to spot using observation tools we currently have at our disposal.

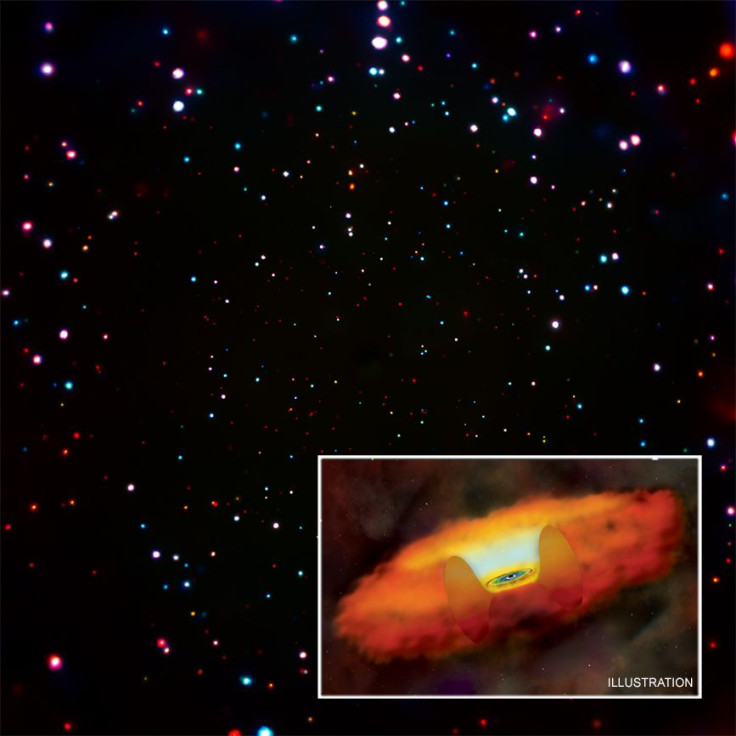

The Big Bang occurred roughly 13.8 billion years ago, and according to data gathered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), supermassive black holes with one billion solar masses existed as long as 12.8 billion years ago. When accreting matter, black holes produce a large amount of heat and electromagnetic radiation, including X-ray emissions which can be detected by the Chandra X-ray Observatory. But it hasn’t found any signs of these rapidly growing black holes that far back in time.

Read: New ‘Direct Collapse Black Hole Model’ To Explain Supermassive Black Holes In Early Universe

Edwige Pezzulli, a doctoral student at the University of Rome and lead author of the paper, along with her colleagues examined various theoretical models and tested data from SDSS and Chandra against them. To form their own model, they formed multiple hypothesis, all of which assumed the growth of black holes could surpass the so-called Eddington limit, where the inward pull of the black hole’s gravity is balanced by the outward pressure of radiation of hot gas from within. And they suggest black hole feeding turned on and off abruptly, lasting for short periods of time, during the early years of the universe.

“In our model only about a third of black holes were actively consuming material and growing 13 billion years ago,” co-author Rosa Valiante of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy, said in a statement Wednesday. “About 200 million years earlier only 3 percent of the black holes were actively eating. Timing, it appears, may be everything.”

Read: Computer Simulations Suggests How Supermassive Black Holes Formed In Early Universe

According to their theory, black holes were “light” and only about 100 solar masses when they were born, and were likely the remnants of the earliest massive stars. The sporadic and rate bursts of intense feeding activity caused these light black holes to add bulk in a relatively short period of time, allowing them to grow millions of times in mass in a relatively short amount of time.

“In order to know if we are ultimately correct, we will need to look at larger swaths of the sky in X-rays to see if we can find the early, feasting black holes that our models have predicted. Our results certainly show promise,” Raffaella Schneider of Sapienza University in Italy, another co-author of the paper, said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.