Theatre, Cinema, Concerts Thrive In Madrid Despite Virus

With entertainment venues shuttered across much of Europe, Spain stands out as a cultural oasis where people still go to the theatre and cinema or watch concerts despite soaring infection rates.

"Having the chance to be here with you is a huge blessing and with all my heart I applaud the great efforts being made in this country to defend culture," Mexican tenor Javier Camarena told Madrid's Theatre Royal last week after going months without performing on stage.

In the audience were 1,200 people in suits, fur coats and masks, often the FFP2 type, after having their temperature taken as part of a meticulous safety protocol.

Following a months-long national lockdown at the start of the pandemic, Spain's cultural venues reopened in the summer operating with strict capacity limitations, well-spaced seating policies and bars and cloakrooms closed.

And since then they have never closed their doors, unlike in other countries such as France or Germany.

But it has meant a costly investment by the venues.

The Theatre Royal, where Spain's King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia attended a performance in September, said it has spent one million euros ($1.2 million), part of which went on an ultraviolet light system for disinfecting the auditorium, the dressing rooms and even the costumes.

And the performers themselves are not exempt from these new rituals: as well as respecting the safety distance and protective partitions, the musicians must undergo regular tests and wear masks, except for the players of wind instruments.

"We can and we must" put on these performances, Spain's Culture Minister Jose Manuel Rodriguez Uribes told AFP, who wants to show that culture "is a safe space".

But the pandemic has forced some venues to temporarily shut, such as Barcelona's feted Liceu operahouse which closed its doors in November.

Under the combined pressure of nationwide curfews, public anxiety and economic pressures, many cultural venues are fighting for their survival.

According to Javier Olmedo, director of "Noche en vivo" association which represents 54 concert halls in the Madrid region, "80 percent have not opened since March".

"It's a time of distress."

Many initiatives to bring people back to theatres and concert halls have popped up on social networks, tagged #SafeTheatre or #CultureisSafe, insisting they have not been linked to any outbreaks.

Marta Rivera de la Cruz, deputy head of cultural affairs in Madrid's regional government, readily acknowledges it is "concert halls and live music venues that are facing the most difficult challenge", saying they will need the vaccine to be widely adopted "to get back on their feet".

Until then, the authorities are looking at rapid virus tests.

In Barcelona, 500 people attended a standing-only concert, grouped very close together but wearing masks who had been previously tested in the context of a clinical study carried out in December.

Eight days later, there was no sign of any infection.

It's an idea that could prove to be "the safest way to reactivate the entertainment sector", says infectious diseases specialist Boris Revollo, who led the study.

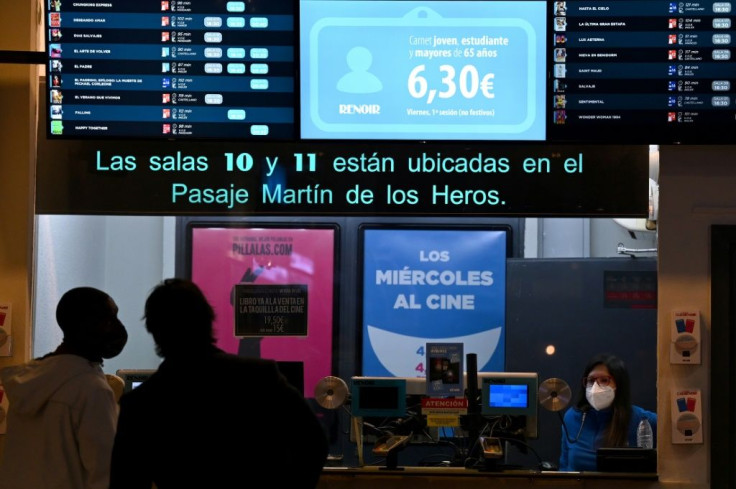

At the Renoir cinema in the centre of Madrid, the cashier's voice crackles over the intercom: "Screen 3, at the back after the escalators".

A risky outing? Not for Paloma Arroyo, 38, who has come to see a retrospective of work by Hong Kong director Wong Kar Wai.

"When you go wearing a mask, you don't talk. People eating popcorn is a bit dangerous, I've thought about that," she jokes, saying such outings were important for protecting her "mental health".

If public transport is considered safe, the cinemas are even more so, says Pablo Blasco, another movie-goer.

"I don't understand why other countries aren't doing this. It seems strange to me."

A few hundred metres (yards) away, old promotional posters outside the Cafe Berlin, a popular live music venue, give nostalgic echoes of the world before the pandemic.

Inside, under bluish lights, the music is powerful and intoxicating, but with dancing banned, the audience can only wiggle in their small velvet chairs facing the stage where the DJ works his magic.

For Maria Llorens, a 20-year-old student, it's not ideal but better than nothing, admitting she misses "that party feeling, with people pressed up against you, and the sweat!"

The club has since closed until further notice due to the economic pressures brought on by the increasing restrictions aimed at slowing infections.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.