Is There Water On Mars? New Study Says Probably Not, Casting Doubts Over Existence Of Life On Planet

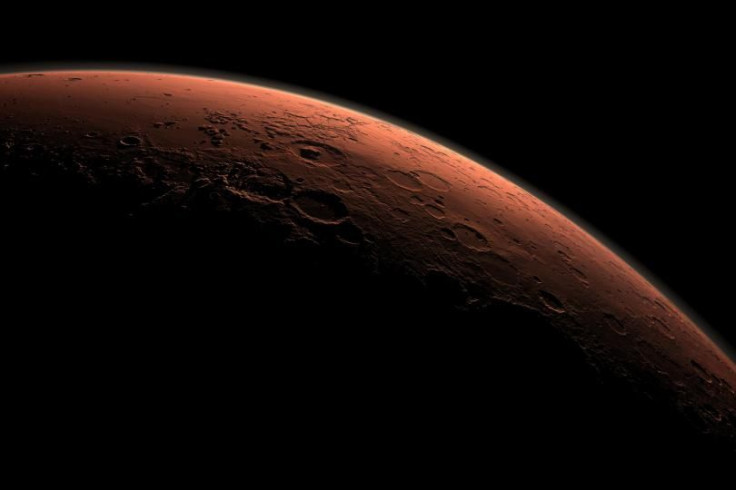

That Mars was once a water-rich planet is now certain beyond a shadow of doubt. What is less clear is when this water disappeared from the surface of the red planet, and if the planet still retains some liquid water on or near its surface.

Last year, in an announcement that generated significant excitement among those looking for alien life within the confines of our solar system, NASA said that its Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter had discovered the “strongest evidence yet” that liquid water flowed intermittently on present-day Mars.

However, a new study published in the latest edition of the journal Nature Communications contradicts this assertion, and states that Mars is, and has been for millions of years, an incredibly dry planet.

“Evidence shows that more than 3 billion years ago Mars was wet and habitable. However, this latest research reaffirms just how dry the environment is today,” study lead author Christian Schröder from the University of Stirling in Scotland, said in a statement. “For life to exist in the areas we investigated, it would need to find pockets far beneath the surface, located away from the dryness and radiation present on the ground.”

For the purpose of this study, the researchers used data gathered by the Opportunity rover, which has been trundling around the surface of Mars since 2004, and analyzed data gathered by it from meteorites in the Meridiani Planum region — a plain in the southern hemisphere located close to the Martian equator.

“The stony meteorites were identified on the basis of their metallic iron content. Although they were discovered serendipitously dispersed across almost 10 km, their chemical and mineralogical composition is virtually identical,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Analysis of the metallic iron content in the meteorites revealed that oxidation, or rusting, rates on Mars were 10 to 10,000 times slower than those in the driest deserts on Earth — something that the researchers say is consistent with a “dry and desiccating environment.”

“The chemical weathering rates presented here represent an average over the past 1–50 Myr [million years],” the researchers wrote in the study. “Our chemical weathering rates are ∼ 1 to 4 orders of magnitude slower than the slowest rates on Earth. Such extreme aridity leads to a drop in the abundance of microbial life to below detection levels even on Earth, as documented for example in the Atacama desert in Chile.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.