Uwingu Exoplanet Naming Contest Provokes Astronomical Controversy

What’s in an exoplanet’s name? A lot of controversy, it turns out.

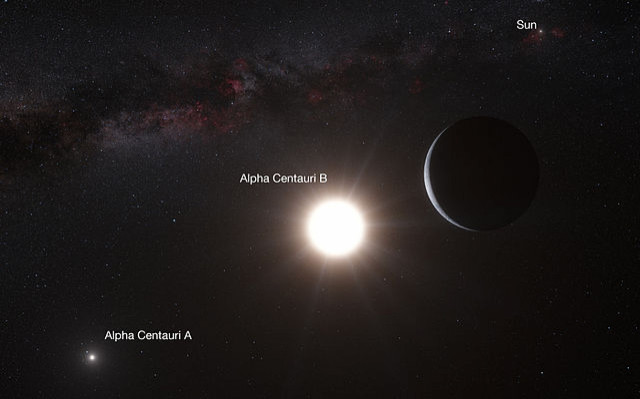

In February, Colorado-based space startup Uwingu launched a site that allows the public to name exoplanets, the satellites that circle stars outside of our solar system. In March, Uwingu opened up a contest to rechristen the closest known exoplanet to Earth, Alpha Centauri Bb, which resides a little more than four light years away. Nominations for possible monikers cost $4.99, and each vote costs 99 cents. Uwingu sends a portion of the money toward creating space-related products aimed at the public, and funding space research and education.

You can also submit names to be assigned to other exoplanets. There are already 861 confirmed planets discovered as of late March, and some astronomers think our Milky Way galaxy alone could house at least 100 billion worlds. That’s a lot of naming to do, and one might assume that scientists need the help.

But the International Astronomical Union – best know as the guys who demoted Pluto to a “dwarf planet” – isn’t buying it. On Friday, the IAU asserted its authority over the naming process for exoplanets, and made some veiled negative references to the Uwingu contest.

“Recently, an organization has invited the public to purchase both nomination proposals for exoplanets, and rights to vote for the suggested names,” the IAU said in a statement. “In return, the purchaser receives a certificate commemorating the validity and credibility of the nomination. Such certificates are misleading, as these campaigns have no bearing on the official naming process — they will not lead to an officially-recognized exoplanet name, despite the price paid or the number of votes accrued.”

Over the weekend, sales at Uwingu dropped dramatically – by a factor of 100, according to Space.com. On Monday, the company hit back, saying the IAU is misrepresenting their intentions.

“Uwingu affirms the IAU’s right to create naming systems for astronomers,” the company said in a statement on Monday. “But we know that the IAU has no purview -- informal or official -- to control popular naming of bodies in the sky or features on them, just as geographers have no purview to control people’s naming of features along hiking trails.”

The company points out that the North Star, Polaris, is known to astronomers by more than a dozen other designations: Alpha Ursae Minoris, and less poetic monikers like SAO 308 and FK5 907. Astronomers also often name features of the sky without going through IAU channels. Earlier in April, NASA nicknamed a supernova (the farthest one yet discovered) after U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, without prompting a scathing denunciation from the IAU.

“They basically said we're conducting a scam, and nothing could be further from the truth," Uwingu CEO and former NASA scientist Alan Stern, told Space.com. "They basically put us out of business, and they've ruined our reputation."

The IAU has also hit out against the commercial practice of selling naming rights to stars or “real estate” deals involving other planets or moons in our solar system. And the IAU points out that the proliferation of private naming operations could lead to confusion when multiple names are attached to the same planet or star.

Although Uwingu’s commercial planet-naming venture might seem a little undignified at first blush, it doesn’t seem exactly right to lump in a venture that enjoys the support of many astronomers and that has already raised thousands of dollars for space research and education in with late-night infomercial scams. Currently, Uwingu is funding Astronomers Without Borders, the Galileo Teacher Training Program, and an engineering bootcamp for high school students at Purdue University. Uwingu also previously raised $2,500 for the Allen Telescope Array, which the organization SETI is using to look for signs of extraterrestrial life.

There’s also the public interest aspect of the planet-naming process – it might be easier to get the average person excited about space if planets had names like Arrakis or Tatooine versus the current number-and-alphabet soup.

“Look, we all know astronomers are terrible at naming things. We call asteroids that get near the Earth ‘near Earth asteroids,’” astronomer Phil Plait, one of Uwingu’s advisers, wrote in an endorsement. “And ‘Alpha Centauri Bb’? C’mon!”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.