What Are 'Boomerang' Earthquakes? Scientists Record Rare Type Of Tremor In Atlantic Ocean

KEY POINTS

- Researchers tracked a 'boomerang earthquake' in the ocean for the first time

- Boomerang earthquakes tend to reverse course instead of going in one direction

- Such earthquakes are believed to be quite rare

- The researchers' data could help with future earthquake impact models

Scientists recorded a "boomerang earthquake" in the Atlantic Ocean, and they believe the findings could help with earthquake impact forecasts.

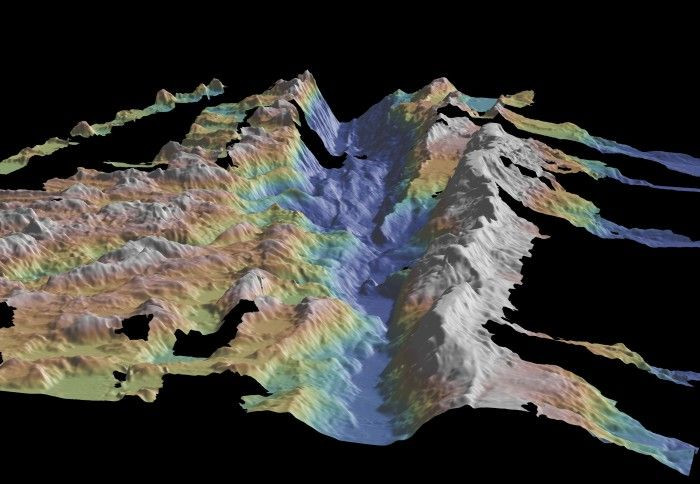

A team of researchers placed a network of 39 underwater seismometers near the mid-ocean ridge in the Atlantic seafloor, some 650 miles off the coast of Liberia. Months later, they detected a magnitude 7.1 earthquake at the nearby Romanche Fracture Zone.

This particular earthquake initially moved upward and eastward before turning back west at incredible speeds. This kind of earthquake is called a back-propagating rupture or, more commonly, a "boomerang earthquake" because of the way that it turns back during the second phase.

In 2010, what appears to be a boomerang earthquake was also detected in Baja California when local residents reported seeing a cloud of dust that erupted from a crack on the surface appearing to move in the opposite direction instead of going in the direction of the crack, as most earthquakes do. These accounts had remained unconfirmed because of a lack of seismic evidence.

Researchers said only a few such earthquakes were recorded worldwide. An analysis of the data they gathered suggested that it started deep underground near the mid-ocean ridge before it turned back at about 11,000 miles per hour. According to National Geographic, this is as fast as traveling from New York to London in just 18.5 minutes.

The researchers' work is one of only a few observations of boomerang earthquakes and they believe it is possible that the first part of the earthquake could have something to do with the second, unusual part.

"Whilst scientists have found that such a reversing rupture mechanism is possible from theoretical models, our new study provides some of the clearest evidence for this enigmatic mechanism occurring in a real fault," study first author Dr. Stephen Hicks of Imperial College London said in a news release. "Even though the fault structure seems simple, the way the earthquake grew was not, and this was completely opposite to how we expected the earthquake to look before we started to analyze the data."

Although a lot is still unknown about boomerang earthquakes, the researchers say that such an earthquake occurring on land could significantly affect the amount of ground shaking, possibly making the trembles worse.

It is still unclear as to how common boomerang earthquakes are but mounting evidence suggests they could be a little more common than believed. The problem is the assumption that earthquakes only move in one direction.

"Naturally we're not looking for it, we don't expect it to exist," seismologist Jean-Paul Ampuero, of the Université Côte d'Azur, told National Geographic.

The mechanism by which boomerang earthquakes happen has been largely unaccounted for.

"Observations of back-propagating ruptures are sparse, and the possibility of reverse propagation is largely absent in rupture simulations and unaccounted for in hazard assessments," the researchers wrote.

The data that the researchers gathered could help in advancing and improving earthquake impact forecasts. The study is published in Nature Geoscience.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.