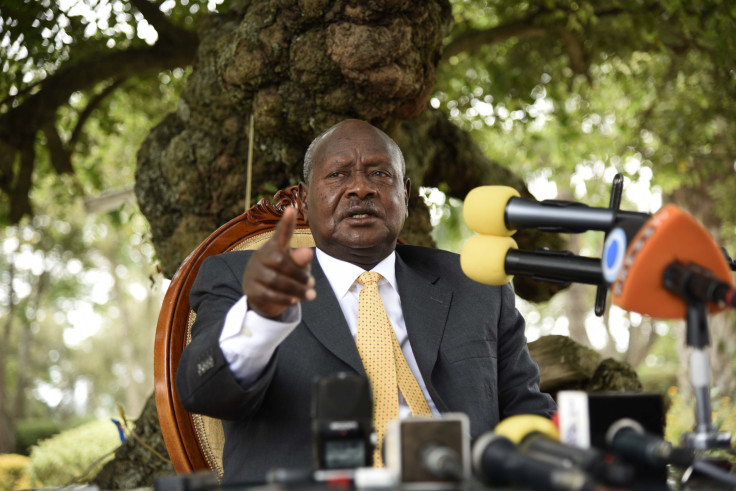

Who Will Succeed Uganda’s President? Museveni's Controversial Re-Election Could Mean Political, Economic Instability

Political fallout surrounding Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s firm grip on power continued this week, following the military court’s decision Tuesday to deny bail to a decorated general and longtime critic of Museveni. David Sejusa, a former coordinator of intelligence services and senior presidential adviser to Museveni, was arrested just weeks before Thursday's general elections after he accused Ugandan officials of plotting to kill those who opposed the veteran president’s plan to hand power to his eldest son, a senior military officer.

Rumors about Museveni’s plan for succession have swirled in recent years, but they came to a boil after the 71-year-old leader was re-elected Thursday. It’s technically Museveni’s last term, as Uganda’s constitution bars any person older than 75 from becoming president. Yet, there are growing fears among locals as well as political and economic analysts that Museveni will try to keep power within his family rather than prepare for a peaceful and democratic transition in the next election. If that happens, it would spell trouble for Uganda’s political and economic climate in the years ahead, with long-term investors already uneasy about the East African country's poor record on good governance and corruption.

“Given his age and how long he’s been in power, it’s definitely something investors are thinking about,” said Ronak Gopaldas, head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank in Johannesburg. “There is a massive question mark on who will take over him.”

Museveni seized power and instituted a nonpartisan democracy in 1986 after winning a five-year guerrilla war against former Ugandan President Milton Obote and Tito Okello. His final term was slated to end in 2006, but he won a campaign to lift the two-term limit on the condition that a multiparty political system would be restored. Uganda threw out its nonparty system that year, but Museveni has been re-elected ever since with little resistance to his rule, partly due to his popularity in his earlier years but also because the opposition has struggled to gain momentum in an uneven political landscape. However, political analysts said his popularity is fading and opposition against him is growing. As a result, government corruption has become widespread and is hindering the East African nation’s economic development.

“Initially his rule was welcomed by a large majority of Ugandans, as he restored peace and a degree of prosperity to the country,” said Nicholas van de Walle, a government professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, who researches the political economy of development, with a special focus on Africa. “As he has become entrenched in power, however, his rule has become more dictatorial, more rigid and less tolerant. Corruption levels among the regime’s elite have exploded.”

Rights activists claim Uganda has not had a free and fair election for decades, and Thursday's presidential poll seemed to be no exception. Museveni won the Feb. 18 election with 60.8 percent of the vote, while his closest rival, Kizza Besigye, received 35.4 percent. Besigye and his Forum for Democratic Change party allege voting was rigged and the opposition leader has been detained numerous times in the past week.

Museveni’s administration also temporarily shut down internet services, including popular social media and money transfer sites, ahead of the election, citing security reasons. The European Union’s Election Observation Mission has condemned Besigye’s arrests and highlighted shortcomings in Thursday's poll, including the issues of neutrality and transparency.

As he enters his third decade in office, there are growing doubts that Museveni will willingly retire and oversee a peaceful and legal transition of power in 2021. There are rumors he is allegedly grooming is eldest son, Kainerugaba Muhoozi, a brigadier in the Ugandan military, to replace him when he turns 75. Sejusa, a member of the military high command, raised concerns about these allegations in a letter to the head of the internal security service in 2013 and called for an investigation, saying those opposed to Muhoozi as a future leader could be targeted for assassination. Sejusa was detained Jan. 31 in the capital of Kampala and is facing charges over his possible links to groups allegedly planning unrest if Museveni won re-election.

Museveni, a former army general himself, has not publicly discussed his purported plans for succession, but his son’s rapid promotion in recent years through a military institution that wields ample power in Uganda has fueled these fears. There are also concerns the aging leader will refuse to hand over his rule altogether and will try to change the constitution yet again so he can run for re-election.

Museveni appears to be in good health, but if he dies in office his sudden absence could open up a power vacuum, even though Uganda’s constitution states the vice president must assume the presidency until fresh elections take place. No matter the circumstances, Museveni’s eventual exit from power could herald another period of instability and political party infighting to Uganda, which is worrisome to investors.

Uganda has already seen a significant drop in foreign investment in the past year, which is a vital avenue for economic development and growth. The country’s central bank said Tuesday that foreign direct investment inflow into Uganda plunged by $200 million in 2015, due to a global economic slowdown and the recently concluded general elections. This is not unusual in the year leading up to a presidential election in an African country and investors who are already doing business in Uganda are unlikely to withdraw now. Infrastructure investment is helping improve Uganda's transportation network and electricity generating capacity, with positive spillovers into key economic sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. But Museveni’s controversial win in Thursday's poll and the uncertainty surrounding his succession will make new investors wary, economic analysts said.

“The issue of succession is something that’s definitely going to make long-term investors in the country nervous, given the fact there could be political turmoil down the line,” Gopaldas said in a telephone interview Tuesday. “They’ll be reluctant to make a full commitment."

The economic anxiety contributed to a sharp decline in the Ugandan shilling last year, with the local currency shedding at least 20 percent of its value against the dollar. It also sparked a rise in domestic prices and uncertainty for consumers and investors. Ahead of last Thursday's concurrent presidential and parliamentary polls, locals said some foreign investors in Kampala and other cities relocated their businesses outside of Uganda in fear of violence. The shilling currency has largely stabilized now, but Ugandan opposition politician Ronald Adubango, who ran for parliament as the candidate for the Justice Forum, or Jeema, and lost, said these investors have not returned.

"The elections are over, but people are still really nervous because the election was unfair," Adubango, 27, said in a telephone interview Wednesday. "The economy of Uganda is down; the rate of inflation is high, and there's a lot of corruption."

Ugandan citizen Robert Agenonga said he is not worried about political instability if Museveni dies while in office, but he feels strongly that the Ugandan leader will not relinquish power without a fight if he makes it to the end of his fifth term. Agenonga, 23, said he is also concerned by the unwavering support Museveni received for his re-election from other veteran African leaders, including those in neighboring Kenya and Burundi, despite the opposition’s allegations of ballot rigging.

“This sends a negative picture to Ugandans,” Agenonga, a human rights activist and freelance journalist in Kampala, said in a telephone interview Tuesday. “There is no democracy in Uganda. As long as Museveni is still here, voting will not make a difference.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.