Wildlife On A Glidepath To 'Mass Extinction': Red List Chief

Nearly 30 percent of the 138,374 species assessed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List are at risk of extinction, the global conservation body reported Saturday.

Habitat loss, overexploitation and illegal trade have hammered global wildlife populations for decades, and climate change is now kicking in as a direct threat, the head of the IUCN's Red List Unit told AFP in an interview.

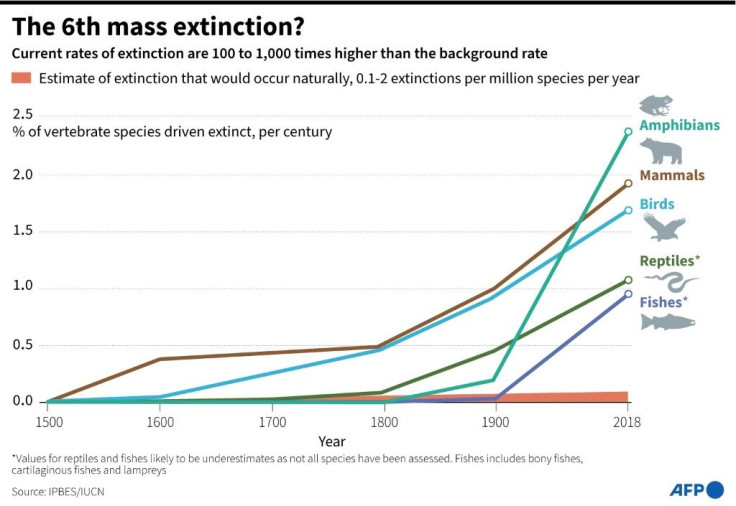

If we look at extinctions every 100 years since 1500, there is a marked inflection starting in the 1900s. The trend is showing that we are 100 to 1,000 times higher than the 'background', or normal, extinction rates. I would certainly say that the red list status shows that we're on the cusp of the sixth extinction event [in the last 500 million years].

If the trends carry on going upward at that rate, we'll be facing a major crisis soon.

A: The initial list wasn't really based on scientific criteria. It was more of a gut feel: 'We think the species is under some degree of threat'. But as the list started to grow, we realised that we needed to make the list scientifically defensible. So we took a big step back and asked: 'What is it we are trying to measure?'

The answer was quite simple: risk of extinction.

A: There are lots of species around the world that we would almost certainly have lost. The Red List process drew attention, for example, to the plight of the Arabian oryx and led to conservation efforts -- taking the animals out of the wild, captive breeding, reintroductions. We've seen species very nearly extinct that are thriving now.

A: The Red List is not policy prescriptive, it's really just a statement of fact -- this is what the status of the species is. Then it's up to the decision makers to interpret that and decide what policies should be enacted.

A: There is lots of lobbying. Surprisingly, it's not so much about the up-listing to a higher threat level. For some high-profile charismatic species, if you want to down-list them because there has been successful conservation actions, we often get lobbied very, very hard to not do that.

There's real concern that if a species goes down a category, that conservation investment will stop. This is where the 'green status' will really help.

A: After you've done the Red List assessment, what are you going to do about it? This is where we started talking about the green status. How do you measure whether your conservation actions are being successful? If we hadn't done anything, where would it be now? If we stopped all conservation efforts now, what will happen to that species going forward? Those are the metrics in the green status process.

A: There's a limited amount of funding available and vast number of species. It does come down to some really harsh realities. You're obligated to just let some species go extinct because we really can't save them.

But it's not something we tackle head on in the Red List process. We effectively pass the buck on to others to make those very hard decisions.

A: It is obvious for the polar bears because of the direct link between sea ice cover and global warming, but with other megafauna it's a lot harder to detect the impacts of climate change.

There is evidence pointing to climate change for the increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires. But when experts record threats to a species they may put 'increased fire frequency', not climate change.

The chytrid fungus is wiping out amphibians all around the world, and we are pretty sure that its emergence is very much linked to climate change. But with the evidence we have now, the category of threat is invasive species, not climate change.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.