3D-Printed Implant Fuses With Bone To Repair Broken Limbs

Most of us have had a broken bone at some point in our lives and we can all agree that it is not a pleasant feeling. Our skeletal system, though not fragile, is susceptible to an occasional crack or a full-blown broken bone.

Most fractured bones are just left alone to heal. Wearing a cast and popping painkillers seems to do the trick for most. But in some severe cases, metal plates or screws are needed to repair the bones, making the process painful and drawn out.

With growth in medical technology, 3D printing is seen as the future of manufacturing and is already a common addition to most colleges and laboratories.

Now a newly-developed 3-D printed ceramic implant not only helps mend broken bones, but it turns into natural bone to repair broken parts.

The implant was made by Hala Zreiqat, a professor and researcher at the University of Sydney, Australia, and her colleagues.

The material, which has been under the testing phase for a few years, has shown promising results in healing broken arm bones in rabbits.

Now, the team was successfully able to repair large leg fractures in sheep, displaying the superiority of ceramic 3-D printed implants over conventional fracture treatment.

The eight sheep in the study were able to walk with the implants immediately after surgery, with plaster casts helping stabilize their legs only for the first month.

The researchers saw complete healing in 25 per cent of the fractures after three months; the healing percentage stood at 88 after one year.

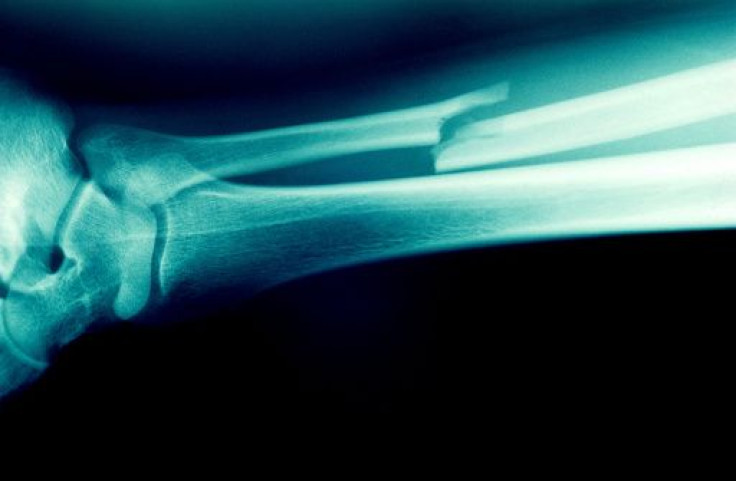

X-rays showed that as the real bones grew back, the ceramic implant blended into the bone, said a release by New Scientist.

Since the early 2010’s, scientists across the world have been experimenting with the potential uses of 3-D printing technology, especially in medicine.

An artificial heart was created in July this year using just a 3-D printer. This artificial but functional heart uses air pressure, instead of muscles like in a real heart, to pump blood to the body. IBTimes reported that this organ can “one day be used to pump blood for people on heart transplant lists, potentially giving them more time to wait for a donor.”

A spate of recent developments in this field could be pointing to a future when we could print a lung when we have a cold, put our real lungs in a machine that removes the infected sputum and flush out the pathogens and then put it back.

We are slowly but steadily getting closer to artificially repairing the human body.

IBTimes also reported in November that a team successfully created tiny blood capillaries with 3-D printing. This was especially tough since some capillaries have diameter of a few thousands of a millimeter, so much so that individual blood cells need to navigate through them in a single-file formation.

Another team were able to create artificial blood vessels that form the basis to any organ construction, way back in 2014. Since then, research in the field has gathered tremendous steam and we are heading closer to a 3-D printed future. With a little more research and fine tuning, the number of people who are already benefitting from 3-D printing could grow manifold, and slowly but steadily the technology will form the basis of any future treatment.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.