Christmas Reindeer Mystery: The World’s Largest Herd is Vanishing

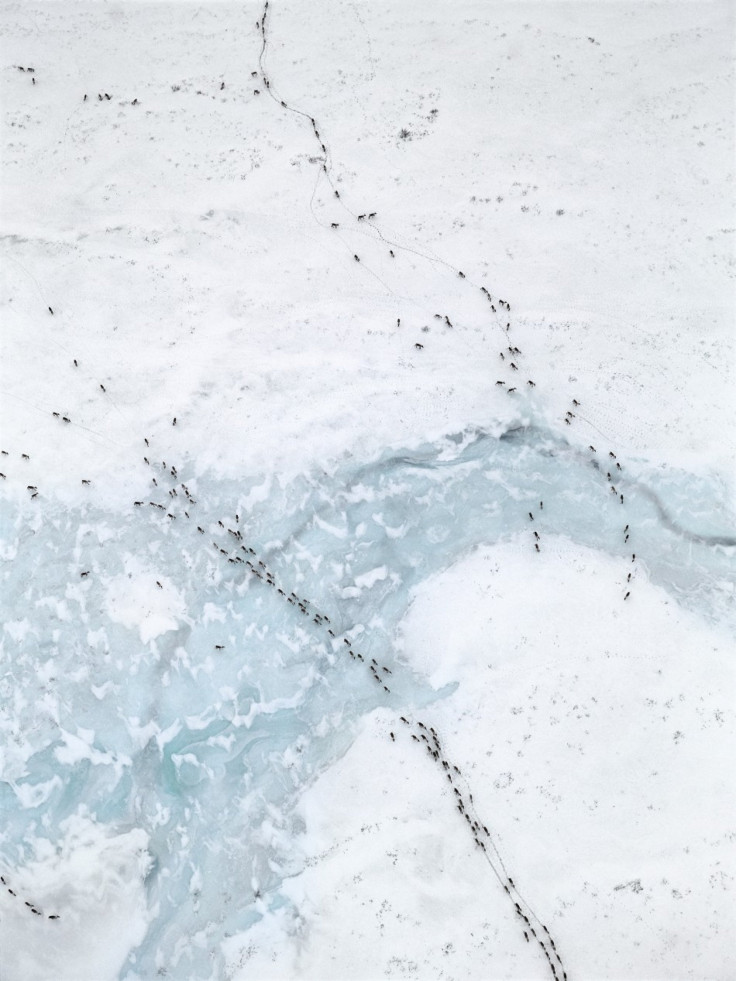

The world's largest herd of reindeer has declined in alarming numbers over the past 20 years.

According to the Department of Environment and Conservation, the population of the George River herd, which ranges from Quebec to Labrador, has plummeted up to 92%, from a peak of nearly 900,000 in the early 1990s to an estimated 74,000 in 2010.

It's ironic, Survival International's Tess Thackara told the International Business Times. As children all over the world leave out carrots by the chimney for Santa's reindeer over Christmas, few know the realities faced by real-world reindeer and the Innu people, for whom reindeer are so central in their livelihoods, culture, and beliefs.

The George River herd of caribou -- as reindeer are called in North America -- lies at the heart of Innu identity.

You hear all the clichés of Indians dancing around and shouting, but the real reason why Innu dancers are dancing, shouting, and rejoicing when they're happy is to please the caribou, Armand MacKenzie told the International Business Times.

MacKenzie was born and raised in a traditional Innu community in Labrador, Canada. His father was a hunter who spoke only Innu, but MacKenzie took a different path. He graduated from the University of Ottawa law school and became an advocate for indigenous rights. He's represented Canada's indigenous peoples through UNESCO and helped negotiate the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

People call me a human rights activist, and I don't mind because I strongly believe that as Innu and as human beings we are all equal and entitled to protect our culture, identity and way of life.

After all, Innu means 'human being,' MacKenzie adds.

The Innu -- not to be confused with the Inuit -- number as much as 20,000. They are closely linked to the George River herd of caribou whose range was disrupted by a series of industrial projects in recent decades.

Of course populations are cyclical and numbers go up and down, MacKenzie said. 70 years ago our parents remember when there were only a few caribou and our people were dying of starvation. But nowadays what is different -- and what is crucial -- is the intervention of unnatural elements.

Mining led to an influx of crisscrossing access roads, logging further destroyed habitat, and the flooding of areas crucial to caribou reproduction for hydro dams hindered their ability to reproduce, MacKenzie said.

Throughout it all, we felt a lack of consideration of local knowledge and lack of understanding about the cumulative impacts, he lamented.

Others take a different view. Flare-ups in 2009 and 2010 pitted the government against the Innu when they hunted in closed areas. Several conservationists and government officials argued the Innu were, in fact, furthering the decline of the dwindling herd.

Though caribou hunting is an intrinsic part of Innu culture, MacKenzie argued the Innu share a strong bond with the animal and are ultimately interested in its conservation. He maintained government restrictions and limited decision-making power when it comes to the management of the herd that roams their homeland, Nitassinan, are to blame.

The Innu have relied on the caribou for thousands of years. Historically, the caribou were not only means of sustenance, but the animal's skin provided clothing and shelter. They have songs for the caribou and even patterned their traditional clothing in colors that pleased the animal.

The caribou have also become an important symbol of Christmas in the last two centuries - though not the Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer sort.

The Innu celebrate Christmas with a traditional hunt. MacKenzie recalled his father's tales of Innu elders gathering together under a large tent to share caribou and other meat with neighbors as far as 100 miles away.

The special dish for Christmas? Bone marrow with caribou fat.

It's called Atik-pimi and it's like caviar for our people, Mackenzie said. You crush the bone and take out the marrow and boil it and a grease forms on top of the water and from there you would freeze the grease and mix it with the marrow.

Innu still celebrate with drumming, traditional songs, and a feast to rejoice the fact that they have food for the special time of year. Yet, they're worried that a day may come when such festivities won't be possible and the last vestiges of their culture vanish in the dust cloud of modern industry.

We're alarmed by the caribou numbers, MacKenzie said. And in the end, we feel like we'll be the ones that pay.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.