Is Aurous Legal? The Ad-Free Music Streaming Service Was Sued By The RIAA, And It Doesn’t Look Promising

The free music service Aurous was in the music industry’s crosshairs before it even launched, and it took less than a week of its going live for the industry to open fire. The Recording Industry Association of America, which acts as a legal enforcer for recorded music, served Aurous co-founder Andrew Sampson with a lawsuit Wednesday, charging the 20-year-old Florida resident, and 10 unidentified collaborators, with three counts of copyright infringement.

On Thursday, Judge Jose E. Martinez granted the RIAA's request for a temporary restraining order against Sampson, which prevents him and his collaborators from working on the site at all until the two parties meet later this month.

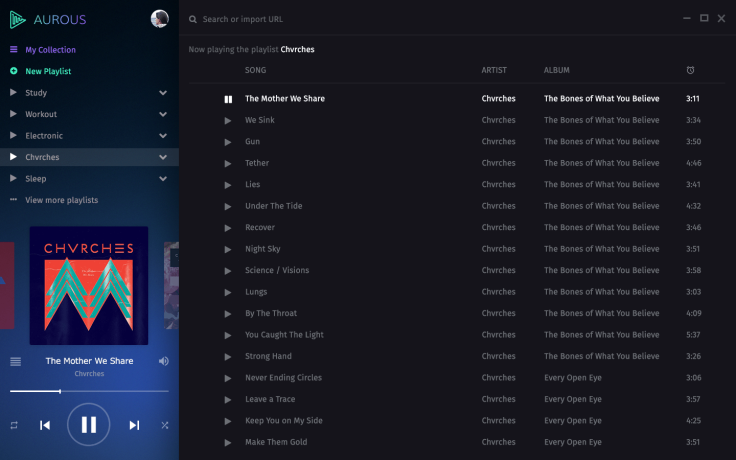

Sampson maintains that the site is on solid legal ground. He has said Aurous does not host any copyrighted material, and that it simply collates music from licensed playlists available on places like Google, SoundCloud and YouTube.

But four legal experts contacted by International Business Times see the case as open and shut, and not in Sampson's favor. “I just don't see the courts ruling in their favor on any level,” said Wallace Collins, an entertainment attorney specializing in intellectual property.

With the music industry betting more and more of its future on the global success of streaming, Sampson ought to have expected the suit. But because he took none of the precautions that services like Popcorn Time and BitTorrent took, it’s possible that the young programmer, who told IBT in an interview Tuesday that his entire platform is built around discussions he had with lawyers, may think he has something up his sleeve.

“If they didn't have an argument for defense, they wouldn't have done this,” said Steve Schlackman, of counsel at Savur Threadgold LLP and the editor of the Art Law Journal.

An Inflection Point

The RIAA responded to Aurous so aggressively because the record industry is at a pivotal moment. Nearly 16 years after it first sued Napster, the world’s record labels have finally managed to get themselves into a position to embrace a new reality, in which people around the world access music instead of buying it.

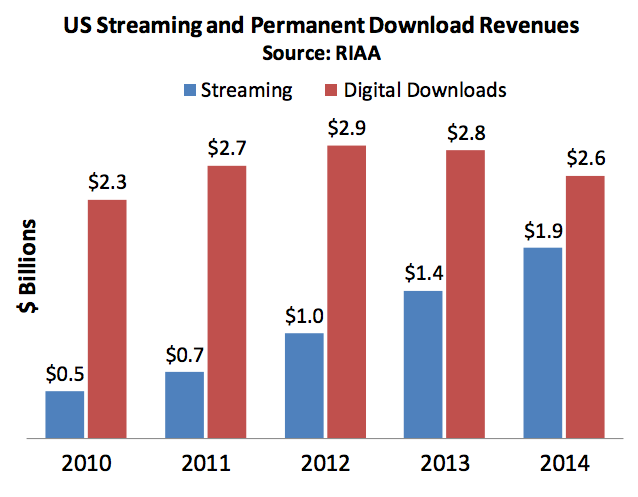

In a sense, it is their only option. The launch of the iTunes Music Store in 2003 accelerated the decline of physical album sales and forced labels to put their faith in download revenue, but after growing healthily through the first decade of the 21st century, revenue from downloads has begun to fall as more and more people embrace the ability to listen to virtually any song they want, on demand.

Seeing that shift, the labels found themselves compelled to look toward streaming as their last, best hope. “They've kind of given up on the ownership model,” Collins said.

That shift meant getting tough and taking a hard line on how much a streaming service should cost. Earlier this year, a number of large labels, including Universal Music Group, reportedly placed intense pressure on Spotify to abandon the ad-supported tier of its service.

Being forced to contend with something like Aurous, which says it won’t charge users anything and will eventually offer users the chance to pay artists what they want, when they want it, would have been unacceptable.

Case Closed?

From a legal perspective, Aurous’s prospects appear dim. The RIAA complaint charges the service with three kinds of copyright infringement -- inducement, contributory and vicarious -- and it has a strong case in two of them.

Inducement, in which an entity provides a third party -- in this case, an Aurous user -- with the means or device to commit a copyright violation, promotes the virtues of doing so, and benefits from that infringement, goes back to suits filed against file-sharing services like Grokster. Aurous, which frames the fact that it is ad-free as a virtue and scans sites that are known repositories of unlicensed content like VK.com and MP3skull, would seem to be in violation.

Contributory infringement, in which an entity provides someone with the means of committing infringement and is aware that providing them with that means will lead to infringement occurring, seems to apply here as well. The Aurous website, filled with copy boasting of the completeness of its catalog and screenshots of music that is not available for free anywhere else on the Internet, suggests they may be liable on this front, too.

“I think it's pretty obvious they're aware of it,” said Allen Bargfrede, the executive director of Rethink Music.

In the case of vicarious infringement, the test is whether profits are being generated at the expense of the infringed parties. That may be a little bit harder to prove, as Aurous currently does not make any money, either through advertising or other means; Sampson declined to comment on his plans to make money from Aurous in an email exchange with IBT Tuesday.

End Game

Ultimately, even if Aurous’s lawyers have isolated some loophole that gets them past all the tests laid out above, that may not be enough to save them. “You have to put yourself in the seat of a judge,” Schlackman said. “You’re trying to use a technicality and an exception to get around the law. And in the end, the court’s going to say, ‘Who cares?’”

"The judge knows what's at stake," he added.

Sampson seems undeterred by the prevailing legal opinions. “I’m pretty confident we’re going to laugh it out of court,” he told International Business Times. “There’s nothing in the complaint that has any merit.”

Viewed outside the context of the lawsuit, there are one or two minor fixes to Aurous that could shield it from legal repercussions. Sampson could cut off access to sites like MP3skull, and allow people to access only legal sources.

But in some ways it’s already too late for that. “[A judge] can't say, 'just do it this way and I'll let it go,'” Schlackman said. “The case is the case.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.