Holocaust Survivor Stories In 2015: In Poland, The Fight To Get Their Property Back

During the summer of 1939 in Poland, Miriam Tasini's grandfather's flour-making business was thriving. The company, a large mill complex in the heart of her native Krakow, supplied bakeries throughout the southwestern portion of the country. Living in a fancy house that overlooked a river, Tasini said her parents and grandparents were a happy family.

But once September came around, when Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime invaded the country, that happy family life abruptly changed forever. Fleeing Poland, they were forced to leave everything behind, including the family business, which the Nazis claimed as their own. Tasini was just 3 years old.

"They were extraordinary, my grandparents," Tasini, 79, recalled. "They were very successful, and then they had nothing.”

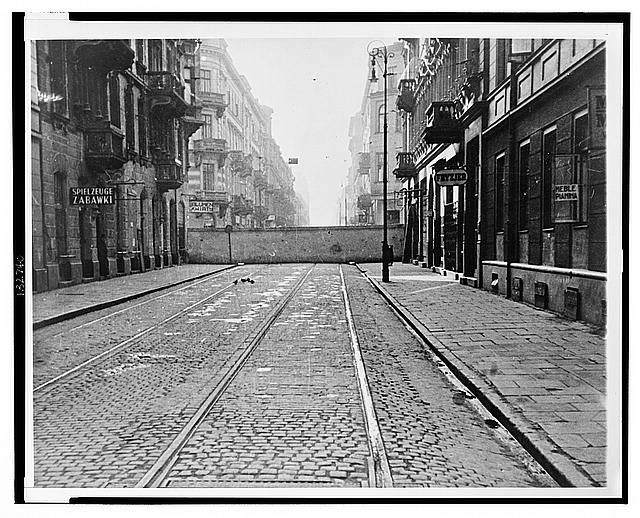

Seventy-five years later, survivors of the Nazi invasion of Poland haven't forgotten what happened to them and their families. Back then, German authorities established a ghetto in Warsaw, the capital, and placed Jews there, typically a prelude to being shipped off to concentration camps to face a nearly certain death.

As a result, acres of coveted Jewish-owned property nationwide were seized during what came to be known as the Holocaust -- the systematic mass murder of Jews by Nazis during World War II. To this day, Poland remains the only post-Communist European Union state that has not passed national legislation on private property restitution following the Holocaust and fall of communism, and those who were forcefully displaced and their relatives have been fighting for the return of real estate they say still belongs to their families. With the Law and Justice Party government that recently came to power in Poland and a greater focus by the EU on making restitution a reality, remaining survivors have continued to push for legislation that would return what was once rightfully theirs.

“Poland has to have the decency to give it back to the owners, and not just Jews, also Poles,” said Jehuda Evron, 84, a Holocaust survivor who serves as the president of the Holocaust Restitution Committee and currently lives in New York City. “The biggest problem is that after survivors suffered so much during the Holocaust, they are forced to have additional suffering by not having justice.”

Like Tasini, who has spent more than a decade fighting for her grandfather's factory complex in Krakow, Evron and his wife, Lea, have been working in excess of 15 years to have property in the Polish town of Zywiec returned to them after it was taken during the Holocaust. Lea's parents owned a tannery, as well as a residential building.

Property Ownership

Poland has undergone dual layers of property changes, said Karen Auerbach, an assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who focuses on the social history of Polish Jews. The country's Jewish population left behind a vast amount of property that was often taken over by non-Jewish neighbors both during and after the war. During the communist takeover after the war, property ownership was again transformed for both Jews and Poles through nationalization.

“It’s a very complicated issue that affects people on an everyday level and is very emotionally charged on every side,” Auerbach said, describing private property restitution. She noted in Poland today, there are ongoing “sincere efforts” to increase dialogue between Poles and Jews to discuss a complicated past, but property remains a touchy issue.

Poland’s pre-war population consisted of more than 3.3 million Jews -- the largest in Europe. In Warsaw, the Jewish population of approximately 350,000 made up about a third of the population. Nazi authorities sealed off the Warsaw ghetto Nov. 15, 1940, confining hundreds of thousands of Jews into an area that was slightly larger than a square mile. Jewish-owned property, as well as schools and religious buildings, were seized as Poland’s pre-war population of Jews was largely decimated.

Evron said he has more than 20 folders of documents and correspondence about the building and factory his wife’s family owned before the war. Most of Evron’s wife’s family died at the Auschwitz concentration camp. He estimated he's spent approximately $20,000 on legal fees trying to get the property back. The current owner of the buildings has argued he bought the property in good faith from the government. “I don’t blame him, but he should have checked the records,” Evron said.

The business owned by Tasini's grandfather, Jacob, became a shareholders corporation in 1928, but 98 percent was still owned by the family. The shareholder structure has complicated the legal battle that Tasini, her sister and three cousins are still fighting.

“The Polish government claims that they cannot give us anything because we do not have the shares,” Tasini said. She estimates she has spent around $25,000 in legal fees. Loft apartments valued around $17 million stand on a part of the property today.

Poland’s government has argued repaying the estimated $30 billion to $40 billion worth of Jewish property seized before and after World War II would create a debt crisis. The government debated the issue in 2008 with then-Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who said he would find a resolution to the restitution problem, but then the financial crisis hit, putting discussions of major spending on hold.

“Saying it’s too expensive is not an answer,” said Gideon Taylor, head of operations for the World Jewish Restitution Organization. “Finding a resolution is the right thing to do.”

Lack Of Laws

After World War II, many western European states moved to address private property restitution while Eastern Europe did not begin tackling the issue until the 1990s following the fall of the Soviet Union. Germany began restitution of private property soon after the war under the Allied occupation. Speaking in 1951, then-West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer admitted Germany’s responsibility and agreed to work with the Jewish population “for a solution of the material reparation problem.” The French government set up a Commission for the Compensation of Victims of Spoliations in 1999, allowing Jewish families to seek restitution without any time limits.

An act passed by the Polish Parliament in 1997 has allowed Jewish communities and religious organizations to apply for the return of communal property from 1939. Many applications are still being processed, said Monika Krawczyk, an attorney and the chief executive officer of the Warsaw-based Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage.

“Since 1989, when Poland became democratic, the government and Parliament have not managed to pass any legislation that would address claims of former owners. This has to do with the political reality and the social reality,” Krawczyk said. “I don’t think it’s on the priority list of the new government.”

'Our Last Chance'

Tasini, a Polish speaker who now lives in the Los Angeles area, said she has helped many people pursing property claims and offered them advice. In the early 1990s, she was able to recover a private building owned by her mother that had been used by the communist government; it was dilapidated and full of rats. The $250,000 earned from the sale of the building in 1993 allowed Tasini’s mother to support herself until her death six years later. Tasini is now looking to the country's new political leadership to turn its attention to the issue of restitution.

“Because of the changes [in the] Polish government, we all feel this is our last chance,” she said. “I know we won’t get the property back, but we would like some restitution.”

With fewer Holocaust survivors remaining each year, lawmakers from 18 European states in October wrote a letter to the president of the European Parliament urging him to focus more attention on restitution of property from that era and appoint a vice president to focus on Holocaust survivor issues.

“Now is the time to seek justice, while survivors are alive and too many struggle to meet their basic needs for shelter, food and medicine,” the letter said.

Restitution efforts outside of property have continued to take place across Europe. France announced earlier this month it would pay approximately $60 million to be split among mostly Holocaust survivors living in the U.S. who were taken by train to concentration camps three quarters of a century ago. The fund, which was negotiated last year, will be paid to survivors, spouses and descendants in an agreement that would create a “legal peace” in regard to railroad deportation lawsuits filed in the U.S., Agence France-Presse reported.

Many of buildings in Poland’s major cities that once belonged to Jews now have high property value estimates. But for Evron, regaining property is not about the money. He said he and his wife would donate the funds to charity, but he realizes how important the money could be to other survivors who are currently living below the poverty line in countries including the U.S. and Israel.

“We really always hope. Giving up is not an option,” Evron said. “We have to continue to fight; we owe this fight to the survivors especially the poor survivors.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.