How Foreign Fighters Joining ISIS Travel To The Islamic State Group’s ‘Caliphate’

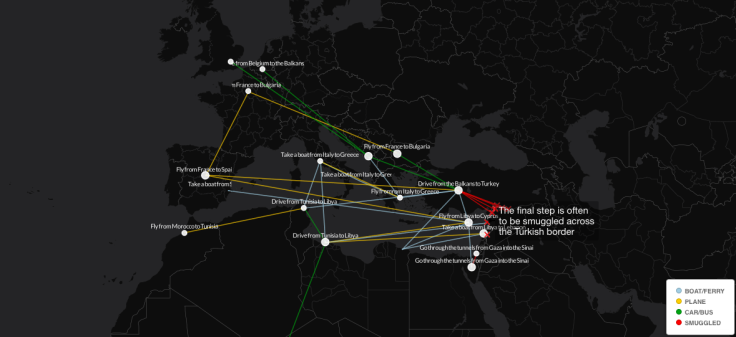

The journey that would-be jihadis take to the Islamic State group’s so-called caliphate can take place over dozens of different itineraries. What used to be a simple crossing of the border into Syria after an uneventful flight to a Turkish airport has now become, for many aspiring holy warriors, a fragmented journey, one that can involve multiple stopovers, bribery and getting smuggled over the border.

Security measures recently imposed by many nations to prevent foreign fighters from joining ISIS, as the Islamic State group is also known, have increased the variety of routes to the caliphate. These new routes often require a combination of land, air and sea journeys. But they all share one element: They end in Turkey, from where the caliphate can be reached by crossing over the porous border with Syria.

The way to get to Turkey has changed, but the country remains the most common entry point to ISIS-controlled territory, as it has been since the group declared itself a caliphate with its de facto headquarters in Raqqa, Syria.

The Turkish authorities know for whom they should be on the lookout. Earlier this month, the Turkish Interior Ministry issued a list of almost 10,000 people with suspected ties to the militant group to be banned from entering the country. The names came from foreign government watch lists and were confirmed by Turkey. There are multiple ways to enter Turkey, however, and many border posts lack the equipment and personnel to monitor all incoming people effectively and accurately.

ISIS online recruiters will assist potential foreign fighters in planning the trip and connect them with people who will take them to a safe house, after which they will be driven to a border crossing and smuggled into Syria, where ISIS fighters will be waiting to pick them up.

Getting smuggled across the border can cost as little as $25 and is generally organized and paid for by ISIS. On the other side of the border, recruits go through training and then, depending on their skills, are deployed to various cities under ISIS control in Iraq and Syria.

Getting to Syria is the easy part of this process. But first, the potential ISIS recruit must get to Turkey undetected.

The majority of itineraries often utilize pre-existing trade, migrant or tourist routes, where an aspiring ISIS recruit can blend in with other travelers.

Air Routes

For most people traveling from North America and certain countries in Europe, getting to Turkey is as simple as booking a flight. Nowadays, it’s likely to be several flights on different airlines so that the end destination does not appear at the initial security check, arousing suspicion.

“Attempts at flying to Istanbul persist, irrespective of stricter air travel security at airports,” Jasmine Opperman, a South Africa-based analyst at the Terrorism Research & Analysis Consortium, said. “What is more frequent is ‘broken flying,’ whereby would-be fighters travel to intermediate destinations.”

Perhaps the most well-known recent example of this type of travel is Hayat Boumeddiene’s escape to Turkey from France. Boumeddiene is the wife of Amédy Coulibaly, the French citizen who killed four people in a Kosher supermarket in Paris in January. Days before the attack Coulibaly drove Boumeddiene to Madrid, Spain, allegedly to meet family friends. From there, she flew to Turkey, where she crossed into Syria. Boumeddiene “did not find any difficulty” on her journey, she allegedly said in an interview published in the ISIS propaganda magazine Dabiq.

Boumeddiene would have had a better chance of being caught had she flown to Turkey directly from France, where her husband was being monitored. For European Union passport holders, traveling within Europe to take a flight to Turkey from outside one’s home country is easy. Under the Schengen Agreement, anyone holding a passport issued by most EU member nations can cross borders within the EU without a security check. The new recruit will only have to show documents to get into Turkey.

Last month, an ISIS supporter published an e-book on Scribd titled “Hijrah to the Islamic State,” a guide on how to make the journey to the caliphate, known as hijrah. The author advises new recruits to “buy a two-way ticket to avoid further suspicion.”

“You can be kind of devious in how you do it, especially in Asia and Europe, but there’s still quite a bit of straight air travel and then taking buses and cars to the border and crossings,” Harleen Gambhir, an analyst at the Institute for the Study of War in Washington, D.C., said. Air travel to Turkey is still the most common route for those leaving from the U.S., she said.

Land Routes

Those who aren’t able to take advantage of the EU’s relaxed border policy because they do not hold a passport from the EU, may already be on a no-fly list or lack proper documentation, can opt to make the longer journey by land. These routes are utilized mostly by fighters leaving from Europe or North Africa.

The most common route for fighters leaving from northern and eastern Europe is to drive or take a bus through the Balkans to the Bulgarian border and enter northern Turkey. Others in Europe can also fly or drive to Greece and use the land crossing into Turkey.

“It is assumed that this is the route for weapons smuggling,” said Dr. Jytte Klausen, a professor of international cooperation at Brandeis University and founder of the Western Jihadism Project, a research group. “Turks living in Germany for years have taken this road for visits home.”

North Africans have an entirely different set of options. The most common end point in North Africa for fighters before getting to Turkey is Libya, where militants in the port city of Derna have proclaimed an offshoot caliphate, pledging their allegiance to ISIS. From there, would-be recruits could take a small boat to Turkey.

Tunisia is also a major transit point for North Africans hoping to join ISIS though Libya. The Tunisia-Libya border is home to various jihadist training camps, including at least one operated by ISIS members. Tunisia has been the No. 1 provider of foreign fighters to Syria so far: As of last October, an estimated 3,000 Tunisians had traveled to Iraq and Syria and joined extremist groups such as ISIS.

Sea Routes

Sea routes are becoming a much more effective way for aspiring fighters to get to Turkey undetected, but the risks of the journey are higher. Potential ISIS fighters can use existing sea lanes used for trade or routes used by migrants trying to flee their countries toward Europe -- except in reverse.

“If you can’t go over land and you can’t leave from the airports, there’s no alternative but the sea. The Mediterranean might become a way because you can take that up the coast and stop at Syria,” said Thomas H. Henriksen, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, based at Stanford University in California. “We’ve had these poor people taking these terrible risks to get across the Mediterranean and paying these unscrupulous guys to shepherd them take them across. Now we have the reverse flow.”

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, NATO began a surveillance mission on the Mediterranean Sea “focused on detecting and deterring terrorist activity,” according to NATO’s website. The operation, called Active Endeavour, expanded in 2003, when security forces began boarding suspect ships, but there has been no documented increase in patrolling since then.

Traveling incognito as a refugee or asylum seeker is not a new ISIS tactic, however, many of the sea routes to the caliphate don’t require that much effort. Ferries to Turkey leave daily from ports on the Mediterranean coast, including in Cyprus and Lebanon. Security at the Turkish ports is very limited and most of the time passports are not checked, Klausen said.

“There’s a fair amount of traffic there, so you can actually hitch a ride,” Klausen said. “There’s quite a lot of boat traffic in that whole region, and it’s not very well policed.”

Smuggling is rampant on the Turkish border with Syria, and it has also become a method of travel for those trying to get to Turkey by sea. For a fee of roughly $500, potential ISIS members can get themselves smuggled onto a cargo ship in Tunisia bound for Turkey, according to Mael Souddi, a Tunisian with family ties to the militant group, who asked that his name be changed for security reasons.

“The jihadists hide themselves in the cargo until they get to Turkey, and no one will see them,” Souddi said. “They get to Turkey without the police asking for their passport or questioning them.”

ISIS Fighters Without A Caliphate

Foreign recruits are the lifeblood of ISIS, keeping it supplied with fighters as it takes casualties from battles in Syria and Iraq. Places such as Spain, Bulgaria and Tunisia that are frequently utilized as stopovers have, so far, been less likely to fall victim to ISIS threats and lone wolf attacks. The locations are strategic for travel to and from the so-called caliphate, and an attack would just increase security on the borders and make it much harder for ISIS to route its flow of recruits through these spots.

Security crackdowns are stemming the flow into Syria, helping the U.S.-led coalition’s effort to defeat ISIS militarily, but ISIS supporters who never make it to the caliphate could still be dangerous at home. The militant group’s leadership has repeatedly called on their supporters to carry out attacks in their home countries if they are unable to make hijrah to Syria.

“If we’re becoming more effective at limiting travel but we’re not pairing that with increased monitoring after someone’s been prevented from traveling, then that could lead to an increase in lone wolf attacks at home,” Gambhir said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.