Huge Chunks Of Antarctica’s Fourth-Largest Ice Shelf, Larsen C, Could Soon Collapse

For Antarctica, this year has not been too good.

In May, a study published in the journal Nature reported that regions of the gargantuan Totten Glacier — the most rapidly thinning glacier in East Antarctica — had become “fundamentally unstable.” Then, in June, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration revealed that, for the first time in 4 million years, carbon dioxide levels at the South Pole have passed the symbolic “red line” of 400 parts per million.

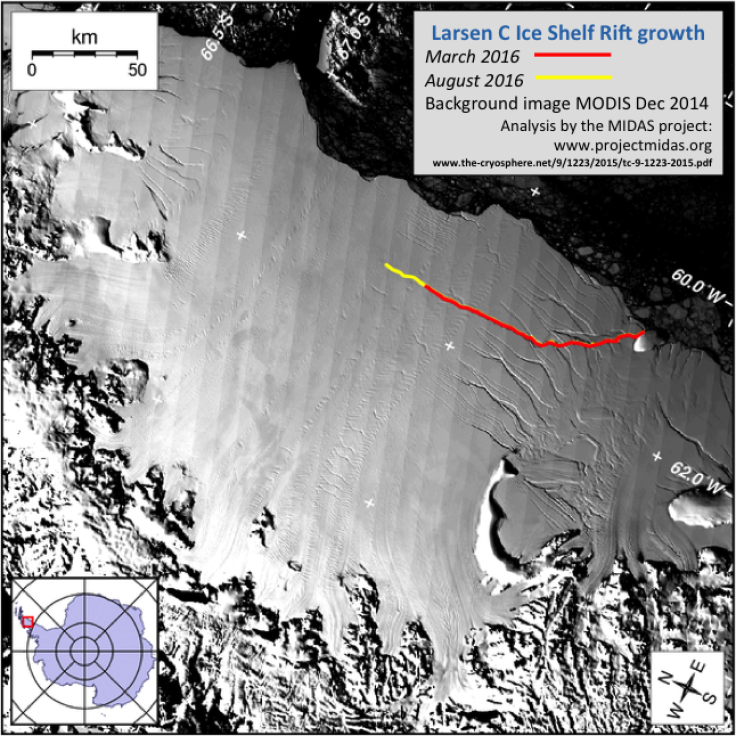

Now, scientists monitoring the condition of the Larsen C ice shelf — the fourth largest Antarctic ice shelf — have witnessed another worrying event. Researchers from the British Antarctic Survey-funded collaboration Project MIDAS reported that the shelf, whose neighbours Larsen A and B collapsed in 1995 and 2002 respectively, now has a huge crack spreading across its surface — one that is growing rapidly.

The rift, which grew by over 18 miles in length between 2011 and 2015, grew another 13.7 miles since it was last observed in March 2016.

“As this rift continues to extend, it will eventually cause a large section of the ice shelf to break away as an iceberg. We previously showed that this will remove between nine and twelve percent of the ice shelf area and leave the ice front at its most retreated position ever. The trajectory of the rift now implies that the higher of these two estimates is more likely,” the researchers said in a statement. “Computer modeling suggests that the remaining ice could become unstable, and that Larsen C may follow the example of its neighbour Larsen B.”

Glaciologist Martin O’Leary — a member of the MIDAS team — told the Washington Post that if this happens, a gigantic iceberg measuring over 2,300 miles — roughly the area of the U.S. state of Delaware — would fall off into the ocean.

“It’s hard to tell how soon it could break – we really don’t have a good handle on the processes which control the timing of the crack propagation,” O’Leary told the Post. “It’s a lot like predicting an earthquake – exact timings are hard to come by. Probably not tomorrow, probably not more than a few years.”

Although the fall of the ice shelf by itself is not going to raise the sea levels — as the chunk of ice is already afloat — it would probably speed up the flow of glacial ice that it currently holds back. This, in turn, would definitely raise global sea levels.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.