Our Thirsty Future: Research Firm Assesses Water Stress Across The Globe

As the saying goes, “water, water everywhere” -- well, maybe not exactly everywhere.

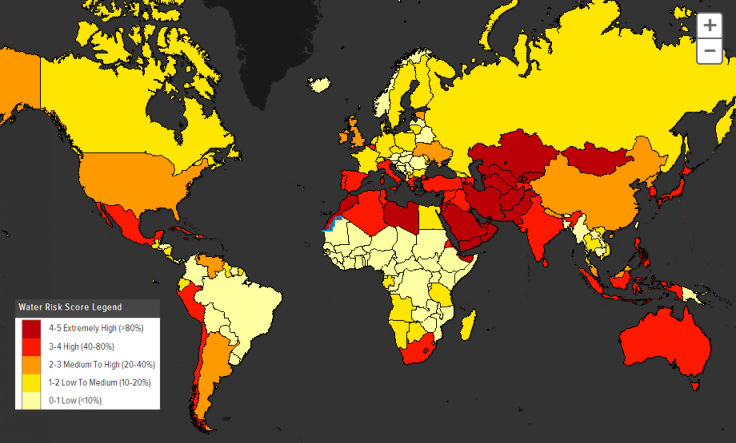

Finding adequate freshwater in a world with an exponentially growing human population is a tricky equation to solve. Droughts can have immediate impacts on people, as well as downstream effects on agricultural and industrial production. The World Resources Institute, a research organization focused on natural resources, recently examined water supply and demand, and flagged 37 countries across the globe as facing “extremely high levels” of baseline water stress. In these countries, more than 80 percent of available water for domestic, industrial, and agricultural use is sucked up every year. It’s a precarious position to be in.

Country-focused analyses of water availability are important, according to WRI associate Paul Reig, because while a river might pass through several political boundaries, the policy decisions impacting a river’s use are often made at the national level.

Also, “many decisions that international companies are making are at a country level,” Reig says in a phone interview.

While Reig says he wasn’t that surprised by the results they found, “there were some scores that might’ve been a bit counterintuitive [to some].” Spain, for example, scored pretty high on water stress, according to WRI’s calculations.

But on the flipside, Reig says, there are countries you might think were especially thirsty that are actually doing fairly well. Egypt, for example, might conjure visions of pyramids in a scorched desert, but the country scored fairly low on WRI’s measure for baseline water stress. Reig attributes this primarily to the fact that Egypt’s population and agriculture is clustered around the Nile River.

How much does a changing climate influence present-day water stress? It’s not quite yet clear. For WRI’s analysis, the researchers used runoff data from 1958 to 2008 (to capture a wide range of years), and compared it to water demand in 2010. Teasing out to what degree climate change might contribute to a country’s water stress is hard with this dataset.

“Runoff is the end product of a number of climatic factors,” Reig says.

Water stress isn’t always a case for hopelessness. Though Singapore ranks among the highest-stressed countries on WRI’s rankings -- with no freshwater lakes or aquifers, and a dense population -- the country has already begun investing in technology to meet its water needs. Rainwater is captured, gray water is reused, and some seawater is desalinated to reduce the amount of water that needs to be imported.

Could the future see wars over water resources? The idea has been floated in many a foreign policy think-piece (and one recent James Bond movie, where a shadowy criminal organization attempts to monopolize Bolivia’s water reserves). But, as Bryan Walsh notes at Time magazine, nations haven't gone to war over water outright in more than 4,500 years -- when the Mesopotamian city-states of Lagash and Umma sparred over access to the Tigris River. Even in a conflict-ridden Middle East, Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority can sit down and hammer out a deal for a large new desalination plant near the Dead Sea that will deliver drinking water to all three parties.

“When you see a number of countries all suffering from high levels of water [stress], is easy to think that that competition could escalate and turn into conflict,” Reig says. “But we think, moreso than conflict, this is going to lead to greater collaboration.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.