California Health Care Fight May Show Democratic Party Future In Trump Era

As Democrats gear up for the 2018 election, they confront big challenges: Polls in the last election showed a general electorate that deeply distrusted the party’s leaders, while new surveys show the Democratic base has lost faith in government — and now many swing voters believe Democrats aim to help the wealthy. At the same time, the restive progressive wing of the party is looking for retribution against Democrats who refuse to turn their populist political rhetoric into concrete policy.

The intensifying health care debate in California most starkly exemplifies the intertwining trends. There, Democrats are facing allegations from progressive leaders that after a decade of promising to create a single-payer health care system, the party is now succumbing to the kind of corporate fealty that national party leaders routinely ascribe to Republicans and President Trump.

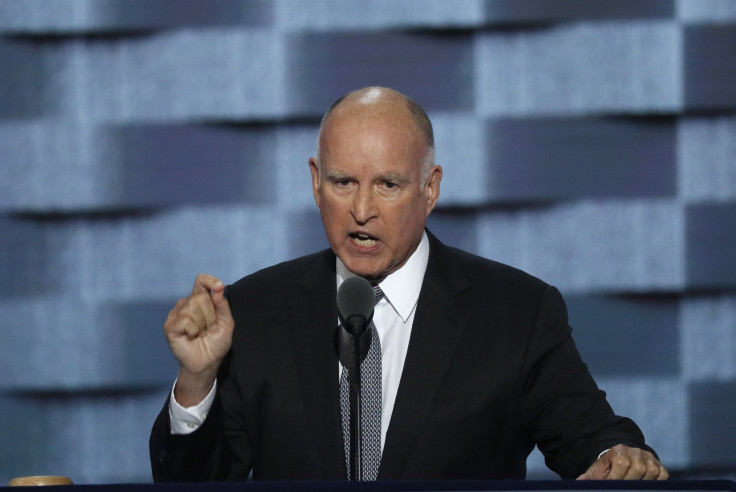

Less than a decade ago, the Democratic stronghold seemed poised to become the first state to create a universal health care program. At the end of the George W. Bush era, California lawmakers twice passed bills to create a government-sponsored health care system that proponents said would save consumers and businesses billions by cutting out private insurers.The only stumbling block appeared to be GOP Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who vetoed the bills. But that seemed to be only a temporary roadblock because the party was on the verge of electing Democrat Jerry Brown, whose father as governor created California’s low-income medical assistance program and who himself had campaigned for president promising to create a single-payer system.

Fast forward a few years, however, and the seemingly inevitable has become the apparently impossible — a stalemate that has fractured the traditional coalition Democrats have relied on to win elections in California and across the country.

As many Democrats enthusiastically promoted single-payer to Golden State voters, the party indeed engineered a complete takeover of the state’s government, giving them unprecedented legislative supermajority power to enact the legislation — even over a governor’s veto. Yet, as health care industry money flooded into the coffers of the Democratic Party’s candidates for California office, Brown has turned negative about the idea, and late last month, California Democratic Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon halted a single-payer bill in its tracks, preventing it from being voted on by his Democratic supermajority before the legislature’s self-imposed July 14th deadline.

Amid calls for Democratic unity in the Trump era, the party’s move in a deep blue state to block a health care initiative it previously supported has prompted labor movement protests — and promises of primary campaigns or recall efforts to unseat recalcitrant Democrats. More broadly, eight years after Barack Obama mounted a populist presidential campaign and then did not prosecute any major Wall Street executives, the episode has resurrected progressives’ allegations that while Democrats may talk a good game, they are not nearly as committed to bold action as their rhetoric suggests.

“Talk about fake news — this is fake politics: stick it to the Republican governor but we’re going to leave dear old Jerry untouched so he doesn’t have to veto this bill,” said Democrat Gloria Romero, a former California Senate Majority Leader who helped pass the single-payer bills in 2006 and 2008. “Probably most of these Assembly members ran for office supporting single payer healthcare. But now that what they ran around promising the people actually has a chance of passage, they don’t dare do what they promised. This kind of thing undermines any integrity from the Democratic Party that is supposed to stand up for the little guy. It creates a disconnect and a distrust.”

In an era that has seen voters enthusiastically respond to populist crusades in both parties, Brown and Rendon have offered technocratic arguments. Both have raised questions about how the most recent single-payer bill, SB 562, would be financed in California, where one previously passed ballot measure constrains the state budget and another requires a set percentage of the budget to be devoted to education.

“SB 562 was sent to the Assembly woefully incomplete,” Rendon declared when he announced his decision to bottle the single-payer bill in the Assembly’s Rules Committee. “Even senators who voted for SB 562 noted there are potentially fatal flaws in the bill, including the fact it does not address many serious issues, such as financing, delivery of care, cost controls, or the realities of needed action by the Trump Administration.”

Those questions also existed in 2006 and 2008; back then, Democrats faced the same state constitutional challenges and would have required waivers from the George W. Bush administration — and they nonetheless passed the legislation. Only now — when Democrats have total control over California lawmaking — are they saying that budget constraints and waivers are a rationale to block single payer. And bill proponents note that Democrats are not raising those same issues about other big-ticket initiatives backed by the governor.

So what happened between the time California Democrats passed single-payer and today?

For one, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act, leaving many Democrats focused on protecting President Obama’s signature legislative achievement against GOP foes — even if that has meant defending a law that still leaves millions uninsured, rather than pushing for the creation of a universal system.

At the same time, an International Business Times review of campaign finance data found that in the intervening years, health insurers and pharmaceutical companies substantially boosted their donations to California Democratic candidates in gubernatorial election years.

In all, donors from the health services sector and major health insurers gave more than $16 million to Democratic candidates and the California Democratic Party in the 2014 election cycle -- almost double what donors from those industries gave in the 2006 election, according to data from the National Institute on Money In State Politics. Donors from those sectors collectively donated more than $3 million to Brown and Rendon since 2010.

In light of that history, longtime single-payer proponents argue that this is a watershed moment for Democrats in advance of the 2018 election. They assert that the California fight will demonstrate whether or not Democrats in the Trump era are willing to use the power they still retain at the state level to defy their major corporate donors and enact the policies they tell voters they support.

“We’ve been talking about this forever,” said Jamie Court, the president of Consumer Watchdog, which has supported the legislation. “When there’s a Republican in charge, Democrats take action,” he said, and with ostensibly pro-single-payer Brown replacing Schwarzenegger, “now it’s time to put up or shut up.”

“It’s a litmus test for whether progressive Democratic politicians can talk the talk and walk the walk,” Court told IBT. “This is about the soul of the Democratic Party as much as it’s about health care.”

“Let This Be Our Long-Term Vision”

When California Democrats first began debating universal health care in the mid-2000s, the idea of creating a state-based single-payer system was hardly a novel one. Brown had floated the idea of creating one “through the 50 states” during his 1992 presidential campaign as he praised the health care system in Canada. That country’s own single-payer system had first started as a provincial initiative spearheaded by a Saskatchewan premier Tommy Douglas — who in 2004 was voted history’s Greatest Canadian in a nationwide survey by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

In 2005, Massachusetts Republican Gov. Mitt Romney and his Democratic legislature began forging a high-profile bill aimed at getting to universal health coverage through a state mandate designed to force residents to buy insurance. In California — which also had a GOP governor and Democratic legislature — lawmakers proposed a starkly different approach: rather than strengthening and expanding the private insurance system, progressive legislators proposed replacing that system with a government-sponsored program mimicking Medicare.

A version of the proposal had already passed California’s state senate in 2003. That bill, authored by then-State Sen. Sheila Kuehl, proposed taking the 70 percent of California health spending that already occurs through various government entities and consolidating it under a new California Health Care Agency, which would “on a single-payer basis, negotiate for or set fees for health care services provided through the system and pay claims for those services.” That legislation became the model for 2005’s SB 840 and its companion funding measure, which proposed new payroll taxes to raise the roughly $100 billion needed to expand health care coverage to all California residents.

The bill was launched with the release of a detailed report by the Lewin Group, a Virginia-based health care consulting firm. The analysis concluded that the measure would reduce overall health care spending in the state by $8 billion a year.

"People believe this is the right way to go, [but] they don't know if this is the only way to go this year," Kuehl said at a press conference launching the bill. "They say, 'Let's develop incrementally.' I say, 'Great. Let's develop incrementally and let this be our long-term vision."'

As Democrats passed the bill through the senate and it moved forward in the state Assembly, it began generating fierce opposition from Republicans and the private insurance industry.

"This government-run health care scheme will jeopardize the quality care that Californians have come to expect and drive businesses out of our state," said Republican Assemblyman Greg Aghazarian, according to the Associated Press.

Though Schwarzenegger originally hailed from Austria, a country with a world-renowned universal health care system, he too staked out his opposition.

"I don't believe in universal health care,” he said in a 2006 speech at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club. "I don't believe that government should be getting in there and should start running a health care system that is kind of done and worked on by government.”

The GOP opposition was boosted by the California Association of Healthcare Underwriters. The insurance industry group issued a study asserting that “the single-payer plan envisioned by Senator Kuehl is a variation of the less-than-successful government-controlled healthcare system seen in other countries such as Canada or Great Britain.”

High-profile Democrats continued to support the legislation.

“California must take the lead in replacing our failed employment-based health care system with a modern single-payer approach that ensures universal coverage and significantly reduces health care costs,” wrote then-Assemblyman Jared Huffman, a Democrat who is now a U.S. congressman.

The bill ultimately passed the Assembly in September of 2006 — but Schwarzenegger vetoed it. Invoking the language of Ronald Reagan, a past California governor, Schwarzenegger declared that “socialized medicine is not the solution to our state’s health care problems.”

In the next legislative session, much the same story played out. Democrats once again passed Kuehl’s bill through the legislature, and used the bill to attack Republicans.

“If the Governor again fails to sign this bill, our health care system will just continue its slide toward becoming a second world health care system,” Kuehl said.

Citing a Legislative Analyst’s Office report, Schwarzenegger once again vetoed the measure, saying the costs were too high.

As the Schwarzenegger era came to a close, Democrats seemed on the verge of securing full control of California’s state government — a position that would give them all the power they would need to pass the single-payer health care initiative they had been championing. Yet, at that very moment — as donors from the health care sector began boosting their campaign donations to Democrats — party leaders’ posture toward single-payer began to shift.

In 2010, Democratic state Sen. Mark Leno shepherded another version of the single-payer bill through the state senate, but the bill died in the Democratic-controlled Assembly on the last day of the session. During the next legislative session, with Brown having won the governorship by a wide margin, Leno tried again — telling the San Bernardino Sun that he was encouraged by Brown’s past outspoken support for single-payer healthcare. The bill, though, was killed in 2012 before even getting out of the Democratic-controlled state senate.

“Political Manipulation By Detractors”

In 2017, single-payer proponents reintroduced another version of their proposal — one that included fewer details than Kuehl’s legislation about how the program would run, but that delegated authority to set up the details of the new program to an appointed board.

Like Kuehl's use of the Lewin Group study, single-payer advocates this time around were boosted by a report analyzing the plan, this one led by University of Massachusetts economist Robert Pollin. The analysis commissioned by California Nurses Association (CNA) found that a single-payer system would reduce administrative costs and negotiate price discounts with drug manufacturers, thereby lowering total healthcare spending in California by 8 percent. To create the program, the report said, California would have to combine its existing $225 billion of government health care spending with $106 billion of new revenue generated from new corporate and sales taxes.

As the bill began moving forward, the California Chamber of Commerce — a lobbying group whose board includes executives from the insurers Kaiser Permanente, UnitedHealthcare, Anthem Blue Cross, Blue Shield of California and Health Net — called SB 562 a “job killer.” It also warned that the taxes needed to fund the bill would have “a detrimental impact on businesses already in California” and would drive away entrepreneurs considering establishing new firms in the state.

In an interview with IBT, Pollin noted that much of the reporting on the bill portrayed the proposal as a $400 billion budget-buster — and did not include context.

“What’s wrong is the notion that we’re going from paying $0 to paying $400 billion,” he said, citing the $367 billion California spent on health care in 2016. “Even with the extra taxes… you still come out better because people aren’t paying high premiums, high deductibles.”

Gerald Kominski, a health policy and management professor at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Fielding School of Public Health, echoed that belief.

“That’s partly political manipulation by detractors,” he said. “Those numbers get thrown around as if they’re dumping $400 billion in new taxes. They’re not.”

Despite the price tag, Democrats in the state senate passed the bill, and the legislation’s primary backer — the CNA — said it began working with Assembly Speaker Rendon’s staff on amendments to fill out unfinished details. But soon after, Rendon announced he would be bottling the bill in a committee, preventing it from being debated, amended or voted on.

“There is no good faith on Rendon’s part,” wrote Michael Lighty, the public policy director of the California Nurses Association, in an op-ed for The Intercept. “Having submitted extensive, detailed policy amendments in advance of the Assembly Health Committee, we expected to follow the legislative process. We prepared to address financing following policy committee approval. We were working to address all outstanding issues through the regular legislative process. Rendon halted that process, so it is disingenuous to claim the bill is incomplete; the process to complete it was stopped.”

Rendon did not respond to IBT’s questions about the amendments.

Protesters, led by the CNA, held an “Inaction Equals Death” rally at Rendon’s district office in South Gate, Calif., on June 27. The following day, and once again last week, angered supporters of the single-payer bill headed to the Assembly in Sacramento, with some staging a sit-in outside of Rendon’s office in the state Capitol. Many on Twitter embraced the hashtag #RecallRendon.

Single-payer supporters are back in the CA Capitol. Lined up to go into Asm rules committee, where the bill has been held pic.twitter.com/l4tRorXoIx

— Melanie Mason (@melmason) July 3, 2017

The scene outside Assembly Speaker @Rendon63rd's office as CNA, Healthy California coalition protests no action on single-payer bill. #caleg pic.twitter.com/1PaxyCPBlT

— Jazmine Ulloa (@jazmineulloa) July 3, 2017

You used single payer as a carrot on a stick. We can't do that anymore. @Rendon63rd #RecallRendon pic.twitter.com/5JdkZYY8km

— Neel Sannappa (@Neelsnapa) July 4, 2017

“There is no perfect piece of legislation, there is always something missing from a bill, you can amend it or you can vote no — but he’s now denying the legislative process,” former Senator Romero told IBT. “If you want to look at a piece of policy you look at the money and how it flows. What the leader of the Assembly is doing, for whichever his sugar daddies are filling his campaign coffers, is protecting his members from having to vote on the issue.”

Rendon’s allies lauded the Assembly speaker for blocking the single payer legislation, even after fellow Democrats had previously passed it.

“I think Speaker Rendon gets a lot of credit for protecting his members from a very stupid idea and making them all politically vulnerable for something that’s not going to happen anyway,” political consultant David Townsend, who works for Democrats and insurance companies, told the Sacramento Bee.

"There Have To Be Electoral Consequences For These Democrats"

Assembly Democrats have set July 14th as the deadline for policy committees to consider legislation this year, and CNA is continuing to stage protests demanding lawmakers allow the bill to be debated.

Whether or not it advances this year, the legislation faces persistent questions about Proposition 98, which mandates a set percentage of spending on education, and the so-called “Gann limit,” which limits overall state spending. A senate analysis of the bill asserted that those measures “would prevent the legislature from creating the single-payer system envisioned in the bill without voter approval” of exemptions.

Rendon’s move, though, has effectively prevented lawmakers from voting the legislation onto the ballot. Kuehl, meanwhile, rejected suggestions that lawmakers could not find creative ways to work within existing constitutional limits.

“That theory won’t fly,” she told IBT, asserting that there is likely breathing room within the Gann limit. She said after a decade of debate over single-payer, lawmakers should be able to come up with ways to deal with Proposition 98.

“I don’t think it would actually be a problem,” said Kuehl, who is now a Los Angeles County Supervisor. “You would craft it so that it would not be part of the state budget. It would create a separate state health plan.”

As for the political dynamics, Kuehl compared the Democrats’ refusal to pass a long-supported health care policy to Republicans repeatedly voting to repeal Obamacare but now having trouble passing a replacement bill under their own party’s president.

“It’s much more realistic when you’re faced with having something happen or not happen,” she said.

Fabian Nunez, a Democrat who served as Assembly Speaker when Kuehl’s SB 840 first passed both houses, said he believes single-payer simply is not feasible at the state level.

“You could do some things at the state level to improve the quality of care, but you need the cooperation of the federal government,” he said. “The only way to do single-payer well is at the federal level.”

Nunez’s position exemplifies the Democratic Party’s shift on the issue now that it has full legislative power. As Assembly speaker in 2006, he supported the California single-payer bill.

Some single-payer proponents in California say that after multiple attempts to pass a bill, Democrats themselves have become the major obstacle — and the only way to get the party to restore its credibility and act on its promises is through threats of revenge at the ballot box.

“There have to be electoral consequences for these Democrats,” said Michael Lighty of the California Nurses Association. “The whole basis of their politics is pro-industry, pro-Wall Street. Those folks are driven by their donor agenda and not by popular demand. There just in general has to be a greater grassroots surge to hold these elected officials accountable.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.