Punishing Syrian Criminals Against Humanity: 15 Regime Leaders That Could Be Indicted

After three and a half years of civil war in Syria and 200,000 dead, few men may embody the brutality of the conflict more than Brigadier General Sha’afiq Masa, the head of Branch 215 of Syria’s military intelligence, a unit often called “the Hell Branch” or “the Syrian Holocaust.”

Masa is in charge of a unit that has produced the highest number of documented torture-related deaths in Syria, according to several human rights organizations that released separate reports after collecting survivor testimonies and eyewitness accounts. Human Rights Watch has accused him of being a torturer; according to the Violations Documentation Center in Syria, his unit has detained untold numbers of civilians in a prison in Damascus featuring a torture room where “80 percent of those who entered ... passed away.” The dead under Masa’s watch, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, now number more than 3,000.

It has been widely reported that at least 37,000 people are still in detention in Syria, many of them tortured every day of their captivity. Torture makes up only a fraction of the human rights abuses committed in Syria since 2011. Yet, until now, those allegedly responsible for the crimes have gone unpunished.

Masa is just one of perhaps dozens of Syrian regime members that have been linked to grave human rights abuses. According to human rights organizations, since day one of the uprising in 2011, leaders in President Bashar Assad’s regime have ordered the killing of thousands of people; had people including women and children shot en masse and dumped in public squares; arrested, detained and brutally tortured civilians in secret police centers; and used chemical weapons to wipe out entire towns.

“When I rule, I rule because that is the people’s will,” Assad said in a televised address in 2012. “There can be no letup for terrorism -- it must be hit with an iron fist.”

The uprising began in March 2011 in Dara’a, when 15 teenagers were arrested for writing anti-government slogans on school walls. They were beaten and tortured, their fingernails pulled out. Since then, the war has become increasingly complicated, and violent.

Nine months later, 36 bodies were dumped in a square in Homs, in a neighborhood that separated the Sunni-dominated section of the city from the area inhabited by Alawites, the Shiite offshoot sect to which Assad belongs. And in the summer of 2012, a massive influx of Syrians began entering Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, seeking shelter in refugee camps on the border.

Refugees in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan told International Business Times in 2012 that security officers working with the regime were kidnapping young girls, some as young as 11, and raping them. One mother said her daughter, Zara Zaytun, was raped by seven soldiers in the suburbs of Damascus after being taken from her home in the middle of the night. Another woman said her son was arrested and tortured by the regime for having connections to the opposition. At that time, the regime was demanding $2,000 to bail each individual out of jail -- a price many Syrian families could not afford. A 21-year-old man, Abdullah, who requested his last name be removed for security purposes, said he was arrested and tortured in Sedanaya prison in Damascus for more than four months, for supporting the opposition. His entire torso was spotted with darkened circles from cigarette burns.

International Business Times gathered testimonies and data from documents published by Human Rights Watch (HRW), Amnesty International, Center for Documentation of Violations in Syria (VDC), the United Nations, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) and the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), as well as its own reporting, and determined that some members of the Syrian regime could be prosecuted for crimes against humanity.

Individuals can be prosecuted for crimes against humanity if they commit widespread and systematic murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, imprisonment, torture, rape and persecutions on political, racial and religious grounds. IBTimes determined that Syrian regime members allegedly committed at least four of those crimes, and compiled a list of 15 Syrian leaders likely to be indicted by the International Criminal Court if the case is referred to its jurisdiction.

This list is not exhaustive. There may be dozens more Syrian leaders who could be connected to human rights abuses, but evidence is hard to collect in an active war zone.

In fact, some of the same documents that could help prosecute Syrian regime leaders for crimes against humanity could also prove genocide. Based on the evidence gathered by IBTimes, some members of the Syrian regime could be prosecuted for genocide for systematically killing civilians in the ethno-religious Sunni majority in the country.

Under international law, genocide is defined as acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, says the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In order to prosecute for genocide, a court with the ability to rule using international law would have to prove that an individual in the regime had a specific intent to destroy a group -- by contributing to a conspiracy to commit genocide, by direct and public incitement to commit genocide, by attempt to commit genocide, or being complicit in genocide.

The Syrian government is not the only party responsible for grave human rights violations. The opposition, specifically the Free Syrian Army, an umbrella rebel organization, has also engaged in crimes such as extrajudicial killings, according to the UN. This list does not address those allegations.

Arbitrary Arrest And Detention

Since the first day of the revolution, and even before, the Syrian regime has been implicated in arbitrary arrests and detentions -- instances where an individual is taken by police officers where there is no evidence they committed a crime, or where there is no due process of law. The Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, an international treaty, both prohibit arbitrary arrest and detention; signatory countries must abide by them.

Syria has adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and is a signatory to the ICCPR treaty. Despite this, human rights organizations and members of the UN Security Council have documented cases when the Syrian regime has breached both in regard to arbitrary arrests and detention.

The Violations Documentation Center, a Syrian monitoring group, reported 37,245 people in detention as of November 2014. In April 2011, Human Rights Watch reported that “Syrian security and intelligence services have arbitrarily detained hundreds of protesters across the country, subjecting them to torture and ill-treatment, since anti-government demonstrations began.” One of the first reports of mass arbitrary arrests and detentions was in April 2011 in Douma, a suburb of Damascus.

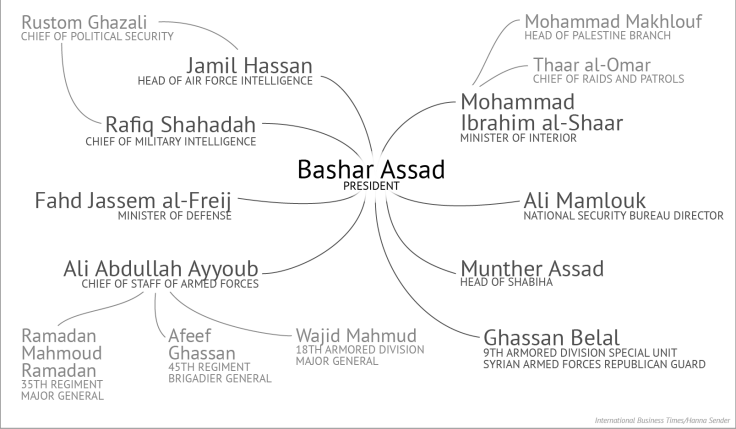

According to HRW, all of Syria’s many intelligence agencies are implicated. The National Security Bureau is supposed to oversee the agencies, but in practice they operate with autonomy and usually answer only to Assad.

Torture

An average of four people die every day in Syria from torture in government-run prisons, according to data from VCD and Syria Deeply compiled by IBTimes. Under the Rome Statute, torture is listed as both a crime against humanity and a war crime and is defined as “the intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, upon a person in the custody or under the control of the accused.”

The number of prisoners who have experienced some form of torture in prison is too great to document, and most human rights organizations are only able to collect data for those who have died. Even those numbers are thought to be lower than the reality, as many of the organizations only include victims whose stories they are able to confirm, document and share.

SNHR was able to document at least 5,514 victims of torture since 2011. The Syrian National Council, the political wing of the opposition, puts the number at 8,069.

Human Rights Watch documented 27 torture centers in Syria, concentrated in the west of the country where the regime has largely been able to maintain control, but “the actual number of such facilities is likely much higher.” SNHR documented 45 different torture methods, including being hung from the ceiling by the wrists for days, electrocutions, “shabeh” (being tied to a low chair for hours and beaten) and “basat al-reeh” (being tied to a flat board with head suspended in the air and beaten with a stick.)

The highest number of documented torture-related deaths comes from Brigadier General Masa’s Branch 215, commonly called the “Raid Brigade.”

Detainees at Branch 215 were put in different “torture rooms” depending on the crime they were accused of committing, according to a testimony from a VDC report released last year. “Detainees with 'terrorism' or 'carrying weapons' charges were taken to room 6 in which 80 percent of those who entered it passed away.”

The unit’s seven-story prison in Damascus city is run by one Ahmad al-Halua, known for his “ugliness,” “dirty mouth” and tendency to search female prisoners, according to SNHR. It houses an underground torture room, and at least 7,500 prisoners who share five bathrooms.

When a prisoner dies, the body is transferred to a “corpses room,” where officers “give every dead body a serial number, the number of dead bodies in that room is now more than 3,400,” a torture survivor who spent seven months in Branch 215 told SNHR. Those details are consistent with photo evidence provided to the UN.

Chemical Weapons

On August 21, 2013, the Assad regime carried out two chemical attacks in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta, killing more than a thousand people, according to a Human Rights Watch investigation which found that a nerve agent was used, most probably Sarin gas.

U.S. President Barack Obama called the use of chemical warfare a “red line” and threatened an intervention that never came. Under pressure from the international community, Syria later agreed to give up its large chemical weapons stockpile, but recently admitted to not disclosing several storage locations.

If brought to the ICC, the Ghouta attack would be considered a war crime, but for Syrian regime figures to be convicted of crimes against humanity the ICC would have to prove the use of chemicals to be “widespread and systematic”.

Syria is not a signatory of the 1993 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling, and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction -- but it is a party to the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, which prohibits their use.

Syrian human rights organizations documented dozens of attacks they claim used “some type of poisonous gas.” SNHR spoke to doctors, eyewitnesses and survivors connected to 25 attacks, even before the 2013 attack on Ghouta.

Extrajudicial killings/ Mass executions

Although the Syrian regime has allegedly committed dozens of extrajudicial killings in the last three and a half years, two instances stand out as perhaps the most severe. The killings took place in two towns, Bayda and Baniyas in Lattakia Governorate, in May 2013. Between the two events, more than 248 people were killed in two days.

In Bayda, the majority of people were executed after government and pro-government forces “entered homes, separated men from women, rounded up the men of each neighborhood in one spot, and executed them by shooting them at close range,” Human Rights Watch reported. At least 23 women and 14 children were killed, including some infants. Following the executions, the government forces piled the bodies in a nearby store and burned them.

In Baniyas, 188 civilians were killed in the village of Ras al-Nabe. Hundreds of civilians who survived fled their homes. At the time of the event, Syrian state news reported that the government were seeking to clear the area of “terrorists.”

Following news of the attacks, the U.S. State Department said it was “appalled” by the violence. “As the Assad regime's violence against innocent civilians escalates, we will not lose sight of the men, women, and children whose lives are being so brutally cut short,” it said.

Enforced Disappearances

In December of 2013, a UN commission of inquiry said enforced disappearances were happening throughout Syria as part of a campaign of intimidation and as a tactic of war. The commission said in its report that enforced disappearances were committed by the regime as part of widespread and systematic attacks against civilians amounting to a crime against humanity.

Investigators on the commission uncovered a “consistent countrywide pattern” of civilians being seized by the security and armed forces during mass protests and house searches, and at checkpoints and in hospitals. The commission requested the regime provide information on the whereabouts of missing civilians, but it failed to comply.

Prosecution

It took the United Nations Security Council months to officially address the crimes listed above; the first resolution on Syria was not passed until April 2012. Drafted by Russia, it acknowledged the “widespread violations of human rights by the Syrian authorities.”

World powers are now beginning to organize teams of investigators to gather information that can potentially help prosecute leaders in the Syrian regime. According to the New York Times, Western governments began discussing in September, behind closed doors, ways to speed the process of bringing those responsible for human rights abuses in Syria to justice. Some Western governments have even begun paying groups to gather evidence they could present in national and international courts.

The International Criminal Court usually only prosecutes individuals serving a state that has signed the Rome Statute. (It is much more difficult to prosecute non-state actors, though possible). Syria is a signatory of the statute, but has not ratified it, so the ICC could prosecute Syrian leaders only if the UN Security Council refers the case directly to the court. That has happened only twice before: For the Darfur region of Sudan in 2005, and Libya in 2011.

Several organizations, including Human Rights Watch, which has done extensive work on the issue, have called on the Security Council to pursue charges against members of the Syrian regime. This year, France, a permanent member of the Council, also called on the UN to send the case to the court. Qatar has commissioned a report outlining widespread and systematic torture in Syrian prisons. A man known in the international community simply as “Caesar” came forward and presented more than 50,000 photos documenting this abuse in regime prisons, including in the Branch 215 prison, and handed them over to the UN. The photos, originally obtained by CNN and The Guardian, documented over 11,000 instances of torture in Syrian prisons.

Senior U.S. politicians have discussed setting up a possible criminal tribunal for Syria, as happened after the war in Bosnia and in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. The creation of such a tribunal would need to be approved by the UN Security Council first. Russia and China may to veto the decision; both have previously vetoed multiple Syria resolutions.

A Syrian war crimes tribunal could be modeled on the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the first court after the Nazi trials at Nuremberg to prosecute people indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity under international law. Its work resulted in 32 indictments.

The question now is whether history will repeat itself. According to a HRW document from 2011, if the Security Council cannot pass a resolution to send the case to the court, then the General Assembly could adopt one that demands Syria “cooperate with the UN Commission of Inquiry as well as the Arab League monitoring mission and urge the Security Council to take action.”

But domestic courts are always the first line of accountability. If they are incapable of prosecuting or are not functional, because of ongoing war, then cases can be referred to the ICC to prosecute.

At the end of her tenure in July, United Nations high commissioner for human rights Navi Pillay said the world had gone backward on human rights. “I, and my predecessors and successors as high commissioner for human rights, can only offer the facts, the law and common sense,” Pillay told the Human Rights Council. Pillay and other advocates in the UN, such as U.S. ambassador Samantha Power, spoke up early about abuses committed in Syria, and supported the creation of commissions of inquiry into the situation there. Although nothing has come of them yet, these commissions produced documents that could provide a solid basis for eventually bringing those responsible to justice.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.