Ten Years In Baghdad: How Iraq Has Changed Since Saddam

When American, British and allied troops rolled into Iraq 10 years ago to topple the regime of Saddam Hussein, Baghdad was a city on the brink. Three weeks of battle wrecked whole blocks of the capital -- but back then, there was room for hope that the rubble could be rebuilt.

Sarmed Kamal Ibrahim, then a 32-year-old engineer, was there when the regime fell on April 9, 2003. He decided to take advantage of the opportunity -- to reconstruct his hometown from the ground up.

“After 2003, I tried to get some contracts to rebuild Baghdad,” he said. But things didn’t go as he planned.

“By 2005, everything was messed up. Terrorists were taking control all over Baghdad and all over Iraq, and they were targeting engineers and doctors. At that time, the sectarian violence was starting. I was targeted by two different groups at the same time, just for trying to help my family run away. Thank God we survived, and we left the country.”

Ibrahim brought his wife, two sisters, his mother and his two young children to Jordan in late 2005. The family then spent three years in Syria before applying to travel to the United States as refugees. They arrived in 2009 and settled in Sacramento, Calif. Since he left, Ibrahim has lost several friends and relatives back in Baghdad.

“We see the news and we talk to people over there -- it comes in waves. Sometimes it’s getting better, but then it goes back to the way it was before.”

When Ibrahim left, he wasn’t alone. According to a report released by the Brookings Institution, about 40 percent of Iraq’s professionals fled the country between 2003 and 2006. Some have trickled back since the violence died down, but the country is still suffering the effects of its prodigious brain drain.

That is just one of the many factors inhibiting Iraq’s recovery. Exactly 10 years have passed since the first American bomb exploded over Baghdad, but the violence has left a lasting mark in Iraqi economy and society.

Falling Apart

It is tempting to blame Iraq’s difficulties on recent turmoil, but the country has struggled with instability since long before the invasion -- dubbed Operation Iraqi Freedom by the adminstration of former U.S. President George W. Bush -- began.

“I think people look at Iraq and ask why things haven’t gotten better. But that’s a poor reading of history,” said Bassam Yousif, an associate professor of economics at Indiana State University.

“Iraq has gone through wars [including the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988 and the Gulf War of 1991] that completely disrupted civil society. They went through years of sanctions [enforced by the UN after Iraqi troops invaded Kuwait in 1990]. They went through de-Ba'athification, which took away a lot of the government personnel. So to expect this country to pop back into shape now is unreasonable. The threats are really quite real, and quite severe.”

When American aircraft began bombing Baghdad on March 20, they were attacking a nation already plagued by instability.

The Invasion of Iraq: Ten Years Later [VIDEO]

The initial phase of the Iraq War sought first and foremost to clear Iraq’s supposed cache of weapons of mass destruction, which turned out not to exist. As the war went on -- especially after its 2010 rebranding as Operation New Dawn -- coalition troops focused instead on establishing order and training Iraqi security forces to combat terrorist cells.

In fact, terrorist groups including Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, which would formally become the Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda in 2004, formed in response to the invasion. The insurgency quickly picked up steam; during 2005 and 2006, American forces and Iraqi civilians suffered their worst losses, prompting the 2007 surge that brought troop numbers from about 144,000 in 2006 to a peak of 157,800 in 2008.

The controversial move helped to quell the tragic uptick in violence. But Al-Qaeda in Iraq, or AQI, is still active today. Most recently, the group claimed responsibility for an attack on the Justice Ministry in Baghdad last Thursday, which killed 22 people.

The incident was just one of many indications that sectarian violence is still rife in Iraq.

About 60 percent of Iraqi citizens identify as Shi'a Muslims, a group that often faced oppression under the 24-year reign of Hussein. His ruling Ba'athist party, nominally a secular bloc, had formed its strongest ties with Sunni communities.

The current government was designed to share power among various groups; Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki is Shi'a, while President Jalal Talabani is Sunni Kurd. But Shi'ites dominate the administration, and Maliki has been accused of monopolizing power.

The animosity between sects was exacerbated in 2012 when the former Vice President Tariq al-Hashemi, a Sunni Arab, was accused of conspiring against the government and then sentenced to death in absentia last September.

In recent weeks, anti-government protests have erupted throughout what the Americans called the Sunni Triangle, an area to the northwest of Baghdad that has historically been populated by high concentrations of Sunni Muslims. The demonstrations have inspired the resignations the ministers of finance and agriculture, both Sunni.

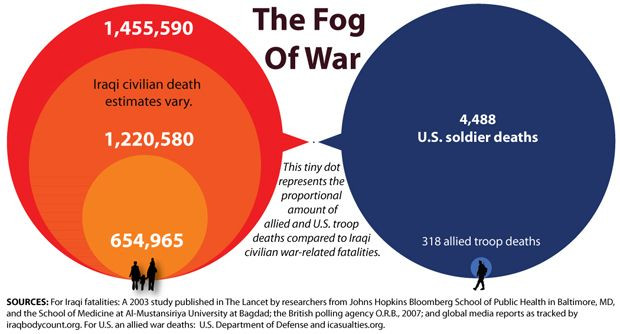

Due in large part to these unresolved tensions, violence in Iraq has persisted even though U.S. and allied troops officially left Iraq in December of 2011. According to the public database maintained by the Iraq Body Count project, 4,573 civilians died in Iraq last year.

Inching Forward

The situation looks dire, but some things have improved since the Saddam Hussein regime was ousted a decade ago. At that time, Iraq was suffering under severe sanctions imposed by the United Nations, which limited the country's ability to profit from its massive oil reserves.

Now that those sanctions have been lifted, growth has been apparent.

In fact, Iraq has the seventh-fastest increasing GDP on earth, according to data from the Economist Intelligence Unit. It reached $170 billion last year, and central bank officials expect it to grow by at least 9.4 percent each year until 2015.

Unsurprisingly, this growth is highly dependent on hydrocarbons. Oil revenues hit $45.3 billion in 2012, up from $5.1 billion in 2003, according to the Brookings Institution’s Iraq Index.

But as is often the case in countries where economies are undiversified and highly dependent on resource extraction, that income hasn’t made a discernible difference for many Iraqi citizens.

Today, about 23 percent of the population lives in poverty. And according to a 2013 background paper released by U.N. researchers this year, “about 60 percent of Iraqi households are suffering from the lack of at least one of the following: access to improved drinking water source, access to improved sanitation facility, a minimum of 12 hours of electricity from the public network a day, or food security.” Unemployment is around 15 percent, according to government data. But that figure may be conservative, and analysts posit that at least another 10 percent may be underemployed.

Iraq’s biggest problem is that oil revenues cannot be easily translated into development. Due to corruption, political infighting and a lack of security, the central government simply cannot spend all the money it makes. When it tries, billions of dollars are liable to disappear due to graft, waste or institutional inefficiencies.

Unable to invest effectively, the government’s hands have been tied. The only recourse has been to dump revenues into the public sector by hiring more and more civilians for government jobs. It’s a top-heavy approach with dim prospects for long-term stability, but it’s been going on for years. Today, public sector jobs account for 60 percent of full-time employment, according to a report from the Middle East Institute.

“People are better off to the extent that they can buy more things, but the economy as a whole is not stronger,” Yousif said. “The domestic economy is unable to produce enough to meet the higher demand, so people are not spending on domestic items -- a lot of it is going toward imports, and to real estate. Property values have gone up astronomically, and that’s where a lot of the money has gone.”

Left behind are some of the industries -- oil refining, agriculture and manufacturing -- that could be key to sustainable growth, if only Iraq were able to devote resources to them.

The central government is keen to diversify in order to shield the economy from volatile oil prices. But until long-term investments become more feasible, it has no choice but to continue throwing money at short-term fixes.

“There’s always the threat of a revival of civil war; there’s always the threat of massive decline of oil prices,” Yousif said. “It’s not that stable a situation. The difficulty is, how do you negotiate that?”

Waiting it Out

It is perhaps no surprise that so many refugees, like Ibrahim, are unsure if they’ll ever return. That creates a vicious cycle -- bereft of so many educated professionals, Iraq lacks the capacity to rebuild.

Although Ibrahim was a successful engineer in Baghdad, he lacks the certifications to do the same work in the United States. To get them, he’ll have to secure American citizenship -- something he hopes to achieve within a year.

“I do have a license for home inspection, so that’s what I’m doing right now,” he said. “Something related to engineering, just to survive.” Ibrahim also runs the Mesopotamia Association, a volunteer organization that helps connect and support Iraqi refugees in the Sacramento area.

Ibrahim won’t go back to Iraq any time soon; he wants his children to stay in the United States because he knows their opportunities would dim if he brought the family back to Iraq. He may consider a return to Baghdad after his children have grown, but only if he can find a way to contribute to development in his home country.

“Maybe I can advise my people in Iraq. Education is my concern. If we can build a good education system in Iraq and give people the right tools, we can build the kind of society that the people have in their minds,” he said. “A new democracy.”

The Invasion of Iraq: Ten Years Later [VIDEO]

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.