Trayvon Martin Update: 3 Years After Unarmed Teen's Death Black Youths Frustrated By Lack Of Progress

NEW YORK __ At 14, Ashanti Cobb’s parents made a point to educate her about the American civil rights movement – the marches, sit-ins and other often-violent struggles for the equal treatment under the law for African-Americans. When a young, black Florida high school student named Trayvon Martin was killed three years ago for seemingly no other reason than that he appeared suspicious to his assailant and later fought with his killer, the reactions to his death looked to Cobb like the bygone civil rights struggles that her parents talked about. “It upset me because I never really thought I’d be around for black history,” said Cobb, a New York City resident who is now 17, the same age Martin was when he gunned down by George Zimmerman, a purported vigilante, who was armed and patrolling the neighborhood.

The details of Martin’s case and others like it have troubled Cobb, who is African-American, and people in her generation for a number of reasons. The top among those concerns is their ability to feel safe in a society where, whether real or perceived, young people of color are viewed as threats. “We don’t often realize it, but what we really lack is safety,” she said.

Three years to the day that Martin was killed, young African-Americans in New York are expressing frustration that their place in society has not improved in substantial ways. Recent high-profile police killings of African-American men and boys in the U.S. -- Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio and Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York – have confirmed to some of them that there isn't a sustainable movement pushing the government to prevent more deaths. But those young people have also grown weary of protests and have little faith that the federal government will do anything to enact solutions. Some of them are resigning to an idea that personal responsibility is the only thing that will keep them from ending up like Martin, Brown, Rice or Garner.

“I think it’s gotten worse for us, and I get the feeling like we’re not wanted in this country,” said Gill Gutt, a 26-year-old native of New York’s Harlem neighborhood. Gutt, a walking advertiser for a New York salon, is biracial. His caramel brown skin suggests to the unknowing that he is more black than anything else, and he self-identifies that way. “I’ve thought about running away from America,” he said. “Just look at the way they vilify us even after we’re the dead victims. They did it to Trayvon and they did it to Mike Brown. They don’t care about us.”

Ashley Howard, a 21-year-old college student from New York’s Brooklyn borough, said Martin’s case didn’t knock her off her feet the way the Brown case did – a Missouri police officer fatally shot the unarmed recent high school graduate after a confrontation last August. “After the Mike Brown attack, I started taking my hands out of my pockets when I walked past cops, to make sure my hands were visible,” said Howard, who is African-American. She worries that her young male cousins experience the same sort of anxieties. “I can’t walk into a store or onto the train without feeling like I’m being judged,” she continued. “I don’t see a day when I’ll blend in with society or be seen as an equal.”

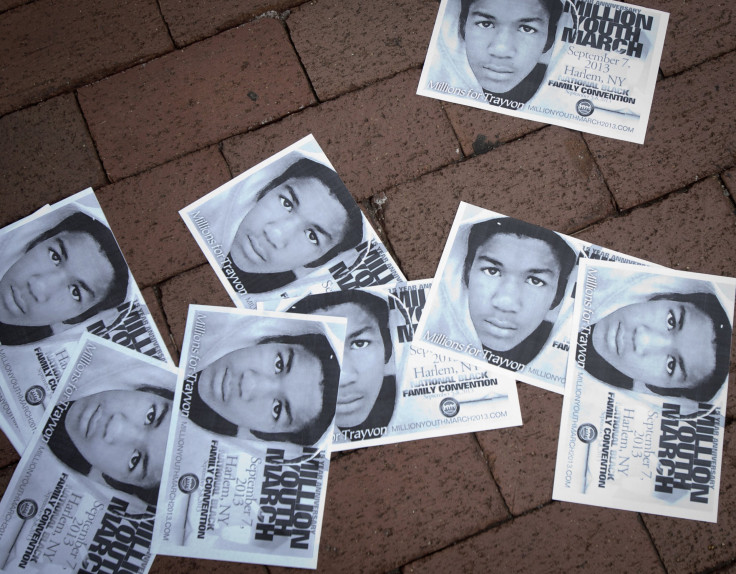

The Trayvon Martin case resonated among young people in New York City. Two weeks before Martin’s death in 2012, 18-year-old Ramarley Graham was shot and killed by a New York police officer, following a chase into his mother’s home in the city’s Bronx borough. Police believed Graham was armed -- he was not. Martin’s parents made frequent trips to the city to publicize their case, the first time after their son’s death for protests and rallies, including the “Million Hoodie March” attended by several thousands of New Yorkers and organized by local activists one month after his death. In the three years since his death, Martin’s mother, father and brother have appeared at numerous events around the country to support other grieving families, including the Browns and Garners.

This week, the Justice Department concluded its promised review of the Martin case and confirmed it would not pursue federal criminal civil rights charges against Zimmerman. Attorney General Eric Holder, who said he prioritized the investigations in the Martin, Brown and Garner cases, said Tuesday that there was insufficient evidence to meet the high standards for such charges against Zimmerman. The findings disappointed Martin’s family, but “steeled” their resolve to be activists against violence against men and women of all colors. “We will never, ever forget what happened to our son, Trayvon, and will honor his memory by working tirelessly to make the world a better place,” Martin’s mother and father said in a statement Tuesday.

Monique Washington, a 28-year-old Brooklyn resident who works in a drug store, said little had come from the Martin protests because too few of the demonstrators appeared to be educated about what to do after the marches. Washington, who is African-American, participated in them initially. She did not join demonstrators when they erupted after Brown’s death because she’s lost faith in the criminal justice system. “The same way the government uses the law to pull us down, we need to know the law to pull ourselves up,” she said. “Tap in, do your research and become familiar with the law.”

Washington isn’t confident that much will change in the short-term. That’s affecting her life decisions. “I don’t know if I want to have a son,” she said. “I don’t know how I would protect him in a world that seems to be after him.”

Martin was killed on the rainy evening of Feb. 21, 2012, inside a gated community of townhomes in Sanford, Florida, about a half an hour north of Orlando. His mother sent him there to stay with his father, while he served a 10-day out-of-school suspension from his Miami high school for alleged marijuana possession. The 17-year-old high school junior, whose mother said he was otherwise a good student, had been walking alone through the gated complex that he’d visited with his father on numerous occasions. He would encounter Zimmerman, but not before the neighborhood watch volunteer dialed 9-1-1 to report his suspicions of Martin.

Martin, wearing a dark-colored hooded sweatshirt and walking leisurely back to his destination, was not casing homes for burglary as Zimmerman initially suspected. The teen had been given permission to walk to a nearby convenience store for a snack. But after Martin returned to the gated community, Zimmerman stopped and questioned him before an apparent scuffle between the two that would leave Martin dead of a single gunshot to the chest. Even after Zimmerman’s trial for second-degree murder in 2013, during which he testified about his encounter with Martin and was later acquitted of all charges by a panel of six jurors, only his side of events in the minutes before Martin’s death has come to light.

Early on, the Trayvon Martin case became a symbol for long-held sentiments in African-American and Hispanic communities that young minorities are endangered because they are judged as a threat by the larger society based on their looks or the color of their skin. The hooded sweatshirt Martin wore became a symbol of protest against racial profiling. The package of Skittles and the can of Arizona-brand fruit juice, two of a few non-threatening items found on Martin after his death, were also used in protests to symbolize unfounded suspicions of young, men of color.

More than two years later, larger protests around the U.S. against the use of excessive force by police in minority communities have co-opted other symbols. In Brown’s case, reports that the 18-year-old had his hand raised in surrender before Ferguson police Officer Darren Wilson fatally shot him became the protest chant, “Hands up, don’t shoot!” The 43-year-old Garner’s last words as New York police Officer Daniel Pantaleo held him in a fatal chokehold, “I can’t breathe,” was also echoed in protests around the country. But in recent weeks, the protests that snarled traffic in large and small cities, and that sparked debates over race and the criminal justice system seem to have quieted considerably.

Civil rights leaders have not forgotten about the Martin’s case, even as others have emerged. “George Zimmerman remains free, while a family continues to mourn the death of a young man—and his memory lies ever present in the minds of his family and Americans throughout the country,” Cornell Brooks, the NAACP president, said in a statement Wednesday about Holder’s announcement that Zimmerman would not face federal charges for civil rights violations.

Indie Ezeigwe, who recently sat down to a game of chess in Union Square where the Million Hoodies March gathered to protest Martin’s death three years ago, said he felt like what happened to the Florida teen and others “could happen to anyone." “I try to control the things that I can control, and if I can’t control them, I don’t concern myself with it,” said Ezeigwe, a 26-year-old African-American resident of the city’s Queens borough.

If young minorities want to prevent more cases like Martin’s, Ezeigwe said he believes people have to speak with their wallets and develop a lasting strategy to keep the pressure up. “Whites get their money out to change things,” he said. “That’s something that can really shift the barometer.” John Hill, a 53-year-old New York City native who works for the parks department, checkmated Ezeigwe in short order. “The fight is only as good as the fighters,” he said of the struggle for civil rights.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.