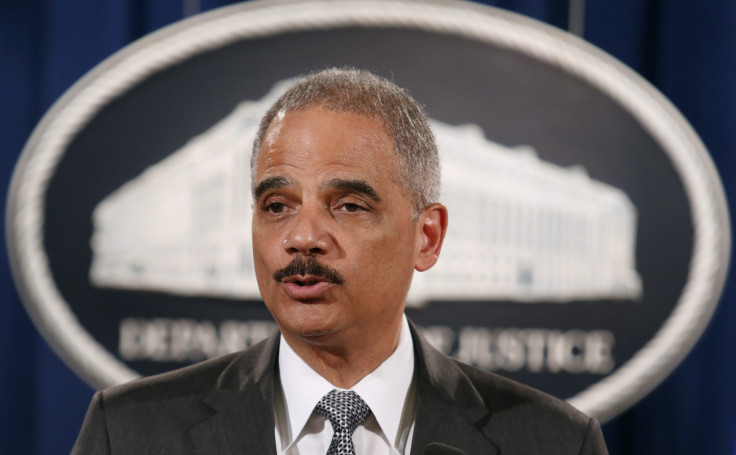

What Is Eric Holder's Civil Rights Legacy? His Achievements Aren't Well Known, Experts Say

Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Eric Garner. The names of unarmed black men killed by police in recent years are etched in the consciousness of people in the U.S. who might have believed that Eric Holder, the first ever African-American attorney general hired by the nation’s first black president, would affect sweeping changes in the ways minorities are treated by the American justice system. Holder’s six-year tenure as the top law enforcement official has been rocky -- he stands as the only member of President Barack Obama’s cabinet to be held in contempt by a congressional committee and censured by House Republicans on issues unrelated to criminal justice and civil rights. That Holder, who announced his resignation last fall, will likely leave the administration without prosecuting a single well-known case of perceived police brutality is a disappointment for many, experts say, even though less-publicized law enforcement reforms have happened under his watch.

“When so many thousands of people have asserted that ‘black lives matter,’ the reluctance by the Justice Department to bring forward a case is more than disappointing,” said Dan Berger, assistant professor of comparative ethnic studies at the University of Washington, Bothell. “I don’t want to put it all at his door, but I think [Holder] has not been as proactive or aggressive in pursuit of racial justice as many would have hoped he would be and that the rather dire circumstances mandate.”

Recent reports indicate that the Justice Department is unlikely to bring federal charges against Darren Wilson, the now-former police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, who shot and killed the 18-year-old and unarmed Brown last August. Neither Holder nor another Justice Department official had made an official announcement about charges on Thursday.

Civil rights experts and some former colleagues have mostly praised Holder, who they say gets little credit for policy changes on racial profiling, war-on-drugs era policing, prison sentencing reforms and his recent work with local police departments where citizens report high rates of excessive force. Earlier this month, Holder called on law enforcement agencies to collect more data in cases of police shootings, calling it “unacceptable” that such data wasn’t being tracked.

In December, Holder announced the expansion of Justice Department rules for racial profiling to prevent the FBI from considering race and ethnicity, as well as gender, national origin, religion, sexual orientation and gender identity when opening federal and national security cases. Also in December, Holder brokered an agreement with the Cleveland Police Department requiring an independent monitor to oversee reforms in the department’s use of force policies, stemming from “a number of high-profile use of force incidents and requests from the community and local government,” according to the Justice Department.

The seeming surge of civil rights activity by Holder in the wake of decisions not to indict officers in Brown’s killing and in the chokehold death of Garner in Staten Island, New York, last year -- which sparked both peaceful and violent protests around the nation -- is anything but a knee-jerk reaction by the Justice Department, said Jon Greenbaum, chief counsel and senior deputy director of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law. “I think that is his record on civil rights will be one of, if not the most shining aspects of his legacy as attorney general -- it’s pretty broad when you look at it,” said Greenbaum, who formerly worked as a Justice Department lawyer and had been in meetings with Holder.

Holder’s career and his outspokenness -- he infamously remarked that the U.S. was a “nation of cowards” on the issues of race -- suggest he is both direct and strategic. Holder was sworn in as the nation’s 82nd attorney general in February of 2009, after Obama announced his nomination in 2008.

Holder was not new to the Justice Department. In 1997, President Bill Clinton named him deputy attorney general. Before that, he’d been a U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia and an associate judge of the Superior Court in D.C. A native of New York City, Holder attended Columbia College and received his law degree there in 1976. While in law school, Holder was a clerk for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The NAACP next month will honor Holder with the Chairman’s Award, during the 46th Image Awards.

Tanya Clay House, public policy director for the Lawyers' Committee, a Washington-based nonprofit that works on issues of racial discrimination and inequality of opportunity, said policy changes that the organization lobbied for had not come out of Holder’s office as quickly as they would have like. But there is a feeling that the Justice Department “was moving mountains” to bring about the needed changes, she said.

Holder also has been praised for his work on voting rights. Early on, he equated voter ID laws creeping up in conservative states in the South with “poll taxes” from the Jim Crow era. Ahead of the 2012 presidential election, Holder filed court cases against voter ID laws in three states, including Texas, that eventually invalidated restrictions disproportionately affecting black, Latino and young voters.

But it’s the Justice Department’s reluctance to use federal authority in the cases involving the deaths of unarmed black men that have puzzled many people who had high hopes for Holder and the Obama administration. Holder had suggested pursuing charges against George Zimmerman for the shooting death of Martin in 2011. But after a two-year investigation, the Justice Department decided against prosecution. A probe in the Garner case is underway and many weren’t holding out hope for charges in the Brown case.

“I can’t say that I’m surprised,” said Rob Widell, associate professor of history at the University of Rhode Island, of the Brown case. Widell, whose work focuses on recent civil rights and African-American history, said: “I would have been more surprised if they did. The standards to prove that violations of civil rights were motivated by race would have been pretty difficult to meet. [Holder] has to make a strategic decision, as much as one based on other factors.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.