The US Government Wants To Patent The Ebola Virus, Here’s Why That’s A Good Thing

U.S. government researchers are embroiled in a five-year fight with the Patent and Trademark office for a patent on the Ebola virus. Though the effort sounds ominous, it could accelerate the pace of research into an Ebola vaccine by preventing pharmaceutical companies from monopolizing the field.

Through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. government often seeks patents on viruses and their genetic material in an effort to research the diseases safely. If awarded a patent, the agency would make the material available for public use, which private companies aren’t as likely to do.

“If a company patents it, they could limit access,” said Robert Stoll, former U.S. Patent and Trademark commissioner, currently an attorney at Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP. “[The government] could donate it to the public.”

And it’s happened before. The CDC holds a patent on the SARS virus from more than a decade ago.

“The whole purpose of the patent is to prevent folks from controlling the technology,” it said at the time. “This is being done to give the industry and other researchers reasonable access to the samples.”

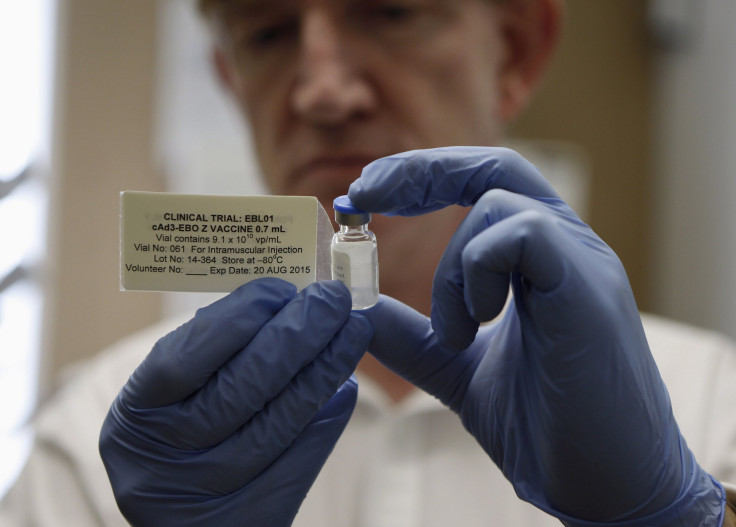

Years before the worst Ebola outbreak in history began sweeping across West Africa, the U.S. government was spending millions of dollars to support research on the virus, which, at the time, held no economic interest for big pharmaceutical companies. Federal researchers at the CDC submitted an application for a patent on Ebola five years ago with the broad intention of helping their own substantial research efforts and to ensure that it remained available to the public.

But patenting a virus isn’t simple. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office continues to deny the application. The case taps into an ongoing legal debate in American courts struggling to apply old rules to new science.

U.S. law forbids a patent on any living thing. But lawmakers probably never envisioned a time when scientists could modify microorganisms or sequence DNA, which has made things complicated. “The legal issues are in a state of flux, and one of the things that got caught up in it with this patent,” said biotechnology and patent lawyer Kevin Noonan.

The CDC has managed to isolate the Ebola virus and modify it so that it is safe to work with, and it argues that this is enough of a change to merit a patent. But the patent office feels it isn’t far enough from its natural state.

The patent application for “Human Ebola Virus Species and Compositions and Methods Thereof” was first filed on Oct. 26, 2009. The original assignee is “The Government of the U.S. as Represented by the Secretary of the Dept. of Health,” and five inventors are listed, all of whom are current CDC employees researching Ebola.

The filing seeks a patent for the processes scientists use to make the Ebola virus safe to work with, research and possibly use in a vaccine. Generally, they have found ways to “attenuate” the virus or make it weak enough to not be dangerous, a common method in disease research. This is typical in disease research. The flu vaccine, for example, contains an attenuated version of the influenza virus. “The big debate is whether it’s enough to simply isolate something from nature and put it in a form that can be safely used,” Noonan said.

There are thousands of U.S. patents for vaccines, but the courts still can’t seem to decide on how to deal with the actual viruses. The 1952 Patent Act, for example, doesn’t distinguish between an invention and a discovery, and the distinction wasn’t clarified until three decades later.

Courts ruled on a landmark case in 1980, Diamond v. Chakrabarty, which involved a General Electric engineer who had developed a bacteria capable of breaking down crude oil, meant to help clean up the waters after an oil spill. The engineer’s patent application was initially rejected on the grounds that federal law prohibits the patenting of any living thing. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, which ruled that “the fact that microorganisms are alive is without legal significance for the purposes of the patent law,” and his patent was issued.

“Basically, you can’t patent a leaf on a tree, or a kidney, but if you have a bacteria and turn it into something that has new properties, then that’s eligible,” Noonan says. But as technology continues to evolve, the rules get even more complicated.

The Patent Office recently released a new set of guidelines to help with the process, based on rulings from cases such as Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, which challenged the validity of gene patents and isolated DNA sequences. Myriad had found a certain sequence of genes that could predict cancer and wanted to patent the genes as well as the diagnostic methods, but the Supreme Court ruled that Myriad had no right to the sequence itself since it can be found in nature. Isolating it was not enough.

The U.S. government’s Ebola patent application involves both of these issues. And the Patent Office isn’t agreeing with the applicant's claims on either. The application has gone through a series of rejections based on different problems.

In its latest rejection published in May this year, the agency wrote that certain features or claims, weren’t allowed under federal law. The latest list of claims shows dozens of corrections and cancellations made in an attempt to comply with the law.

The application includes the U.S government's first claim of the virus in isolation, which was rejected because Ebola is “a natural product and is judicially excepted from patent eligible subject matter, regardless of its isolation by applicants,” the letter says. The application also includes another claim of a killed Ebola virus, a common method used by health researchers, especially in vaccine development. This was also rejected as inelligible, “since killed viruses exist in nature.” Another part of the application includes a claim for the combination of a dead virus with a “pharmaceutically acceptable carrier,” which was also rejected since a carrier “does not markedly change the structure of the naturally occurring product.”

The list of claims itself shows eight withdrawn and 10 canceled since the process began. But despite the lengthy process, the applicants keep trying. And it could pay off. Once a patent is issued, the owner can license it, which means that the owner could sue any entity that was making, using or selling it.

As it stands, however, the application has not been approved, which means that the incredible amount of Ebola research going on around the world will continue. Ebola has already killed more than 4,900 people in West Africa, and drugs are currently making their way through the testing phases in hopes of stopping the outbreak as soon as possible.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.