US Recession Fears: Does The Fed Have The Ammo To Fight Another Downturn?

It's a nightmare scenario for central bankers: After using virtually every tool at their disposal to stimulate the economy and maximize employment since 2008, the Fed watches as the U.S. economy slips back into a recession. As payrolls dwindle and bankruptcies mount, the Fed has a choice — stick it out and hope the economy will right itself, or dig deeper into its bag of tricks and maybe try something that's never been attempted.

This hypothetical scenario has grown into a material possibility in the first weeks of 2016, with banks increasingly worrying that a recession could strike this year. Though the odds remain low — a 1-in-5 chance, according to Bank of America and Morgan Stanley — it's enough to make Fed officials lose sleep.

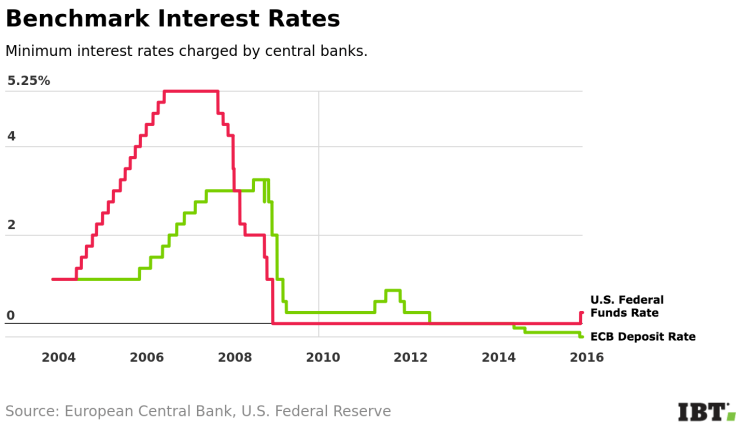

That's because this time around, the Fed doesn't have much room left to pursue its ordinary response to cyclical recessions: lowering interest rates. The Fed's benchmark interest rate currently hovers just a notch above zero, where it stood for seven years after the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Known as the Federal Funds rate, it's what banks pay to borrow money from the Fed, passing the rate along to credit card users and mortgage borrowers.

But with its benchmark interest rate set between 0.25 percent and 0.5 percent, the Fed is left with almost no wiggle room to ease monetary policy and stimulate the economy. That is, unless the Fed pursues historically unprecedented and politically contentious measures, such as sinking interest rates into negative territory.

"It’s not a fun time to be a central banker," said Peter Conti-Brown, a historian of monetary policy and author of "The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve." Legions of critics have accused Fed officials of waiting too long to begin normalizing interest rates, a process that just got started in December. "Get off zero now!" bond guru Bill Gross urged throughout 2015, while hedge funder Carl Icahn has warned that the Fed is taking America down a "treacherous path."

Those criticisms underline the political risks the Fed faces in pursuing policies unfamiliar to the markets, Conti-Brown said. "The Fed is seeing the consequences of their very difficult place in the political econonomy."

Fed Chair Janet Yellen has two general paths she could take if a recession were to strike with interest rates already scraping the lower bound. The Fed could simply bring rates back down to zero and wait it out, hoping that Congress initiates fiscal stimulus and that the recession is short-lived. If need be, Fed officials could also undertake another round of quantitative easing — that is, large-scale purchases of mortgage bonds and government debt meant to juice the economy.

Alternatively, the Fed could push rates below the zero lower bound. "The Fed would be essentially charging banks for their loans, passing that into the economy so that it’s more expensive to keep your funds in low-interest accounts," Conti-Brown said. Done correctly, the strategy would push businesses and individuals to spend their savings, increasing overall demand in the economy and lifting growth.

Though it may sound far-fetched, the idea could work. What's more, it has a precedent: The eurozone has held benchmark deposit rates in negative territory since mid-2014, with some European central banks that don't use the euro following suit. “Our colleagues in Europe are busy rewriting economics textbooks on this topic as we speak,” Fed Vice Chair Stanley Fischer noted in a speech earlier this month.

But a number of market risks might result from central bankers essentially paying banks to borrow money, Fischer said. Money market funds sensitive to borrowing rates could buckle under the stress of a new rate regime. And the complicated machinery undergirding the U.S. financial system might suffer a Y2K-like breakdown. "There could well be automated systems that simply are not coded properly at present to process transactions based on instruments with negative rates," Fischer said.

Another risk is that measures once seen as beyond comprehension become routine. "If the Fed uses unconventional tools for an conventional recession, then they become conventional tools themselves," Conti-Brown said.

If the European experience is any guide, the broader markets shouldn't worry too much, said Angel Ubide, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. "This is something we are all collectively learning by doing," Ubide told International Business Times. "You can cut rates to negative 0.25 and negative 0.5 and nothing breaks."

"What we have to do is stop calling it unconventional," Ubide continued.

While markets might be able to swallow negative benchmark rates, however, politicians may be more resistant. A foray into never-before-seen negative rates would come at a particularly vulnerable time for central bankers. Presidential contenders including Ted Cruz and Bernie Sanders have railed against Fed policy, each vowing to curtail the Fed's cherished political independence. Yellen has repeatedly taken up a defense of the Fed against proposed legislation that would impose tighter bounds on Fed policy.

A negative interest rate "would dominate the news overwhelmingly," Conti-Brown said, upsetting publicity-shy central bankers. In the most dramatic scenario, political pushback could even pose an existential risk, he said. "The Fed could cease to exist as we know it."

With most economists still projecting solid 2 percent growth for 2016, however, it's a risk the Fed hopes it won't have to take anytime soon.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.