Walking As The World Turns: Paul Salopek Merges Technology With Early Human History

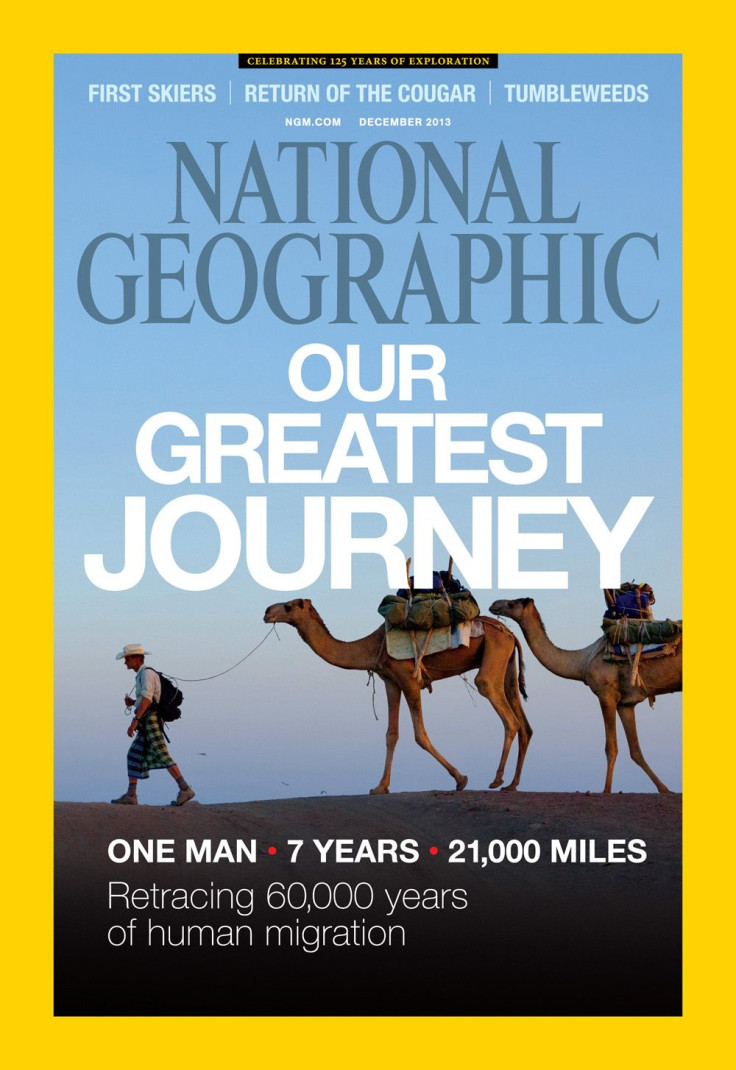

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia -- Journalist Paul Salopek is making an epic seven-year journey around the globe on foot, but this isn't a personal odyssey. It's a global one. “This story isn't mine; it's not just Paul's walk,” he said. “It's everybody's.”

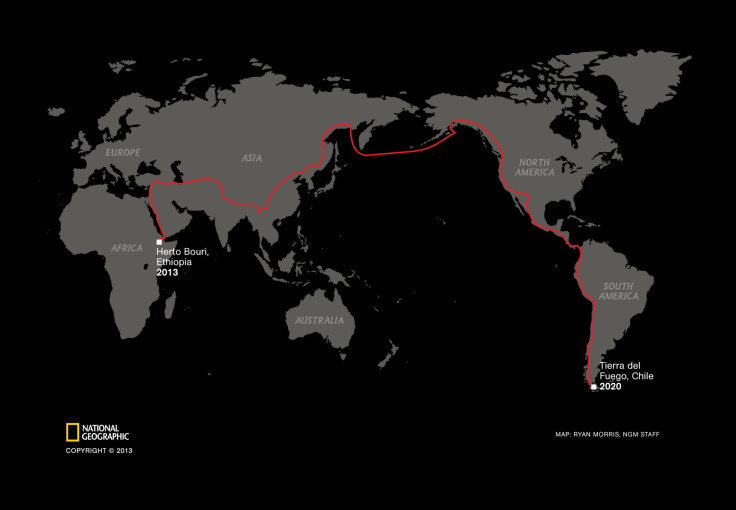

Salopek, an award-winning foreign correspondent and National Geographic Fellow, has been walking for almost a year now. It began this January in Herto Bouri, in Ethiopia's Rift Valley. I called Salopek while he stopped in Jordan, after he had trekked through Djibouti, crossed the Red Sea and traversed Saudi Arabia. In the coming months, he'll go north and east through Asia and into Russia, then across to Alaska and down the western seaboard of the Americas. The last stop will be Tierra del Fuego, at the southernmost tip of Chile.

This route loosely traces the path that modern homo sapiens took beginning more than 50,000 years ago, when some of our earliest ancestors began to fan out from northeast Africa and into the Middle East. Scientists estimate that humankind reached Tierra del Fuego around 12,000 years ago; Salopek expects to arrive there in 2020. I asked him whether his feet hurt, whether his backpack was heavy, and whether he was daunted by the thought of traversing the world for another six years. But Salopek, 51, insists that the journey has very little to do with his own personal challenges.

“It's not possible to conceive of six more years and hold it all on your head; I'm taking it a step at a time,” he said. “I just wanted to put together the strengths of my work into one long narrative, with an interesting idea to tie it all the issues together: class differences, migration, population growth, conflict. The idea is to weave all of this into the story of the human diaspora.”

So Salopek didn't speculate much on how the journey will affect him -- he focuses instead on how the world will change during his trip. A lot can happen in seven years, as it has since 2006. Back then, Western economies were only approaching the precipice of a historic recession. Official planetary status was revoked from Pluto. Forer Iraqi president Saddam Hussein was sentenced to death. Pop artists Shakira and Wyclef Jean topped the American Billboard charts with “Hips Don't Lie.” Wikipedia amassed its first 1 million English articles; now, there are about 4.4 million.

Over the next six years, Salopek suspects the Internet will be a major propellent of social change. Today, penetration rates stand around 30 percent, but by the time Salopek reaches Tierra del Fuego, more than half the world is likely to be connected, with most estimates ranging between 60 percent and 80 percent. But predictions can only go so far, and Salopek is well aware that the life he returns to in 2020 will be profoundly different. Exactly how is anyone's guess. Will the world have made progress on combating climate change? Will Syria be at peace? Who will be the 45th president of the United States? Will poverty-stricken countries have reached their Millennium Development Goals by 2015?

And will the Yaghán language be extinct? For Salopek, this question is personal. He traveled to Tierra del Fuego a couple weeks before his walk began, where he met Cristina Calderón, 84, the last full-blooded member of the indigenous Yaghán ethnic group in southern Chile. She spoke with Salopek during his visit, teaching him the names of household objects in her mother tongue. But her language is a dying one, and there's no guarantee that she will still be there when Salopek completes his long walk.

“I wanted to take her words with me,” said Salopek. “She's a tough old lady; there's nothing romantic or fuzzy about her -- just a great gal who lives in a cabin by a chilly channel, doing her best to remember. That's what I'm trying to do in my journey.”

Traveling the world at three miles per hour is one of the oldest, most-traditional things a human can do. But Salopek is using some very modern tools to keep himself connected to his readers; his website, Out of Eden, features video clips, Instagram photos, and even a compilation of tweets from nearby communities, culled by a super-computer at Harvard University in Massachusetts. A recent Twitter collage from Saudi Arabia captures residents talking about everything from family to technology to politics, revealing more slices of life than one man alone could hope to report on.

“I do conventional foreign corresponding with a notebook, pen and camera if I see an interesting story developing,” he said. “But there's also this layer of digital storytelling; I'm using the Internet and stopping every hundred miles and take a digital recording of the earth. We use photographs, video, ambient sound -- like beads on a string across 20,000-plus miles that, taken together, will be a portrait of what it's like to be alive at this point in time.”

It will be quite a wide-ranging portrait. Salopek has by now grown accustomed to desert landscapes in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East, but now he's trading in his faithful camels for mules who can handle wetter, rockier terrain. He's also prepared to brave snowier climates up north, noting that tundra is actually more forgiving during the winter: fewer flies, better footing. Then comes the southward veer, through some highly developed areas of the Americas' western coastlines, where Salopek is worried that he won't find willing walking partners. What matters to him isn't the landscapes, after all, but the people he meets along the way.

“The people I walk with are a vital part of this trip,” he said. “Some readers think I'm on some kind of athletic excursion, but really I'm looking for the easiest landscapes to move through. My topic is people, so whether I walk with retired oil workers, students, soldiers, they're a part of the journey.”

The more people involved, the better -- which is why technology is so important to Salopek's trek. Readers can follow the journey at Out of Eden or read dispatches at National Geographic, and that connectivity makes this project less about a long walk, and more about a fast-changing world.

“Even though the journey is based on the oldest form of story-telling there is, it was conceived from the very beginning to have this tension between the ultra-fast and the ultra-slow,” Salopek said. “If I don't pay attention to those extremes, it becomes a different project altogether, one about nostalgia or history. History is my guidepost, but the information revolution is very much front-and-center of the walk.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.