Why More Black Engineers Aren’t Being Hired In Silicon Valley

About 5,500 black students earn engineering and computer science degrees in the U.S. each year, but most go unhired by America's top technology companies.

When Joshua Mann set foot in SpaceX on the first day of his internship three summers ago, the scene was not entirely unexpected. “I’ll be honest. When I got to SpaceX there weren’t a lot of black engineers there,” he said. “There was a feeling, did I really belong here?”

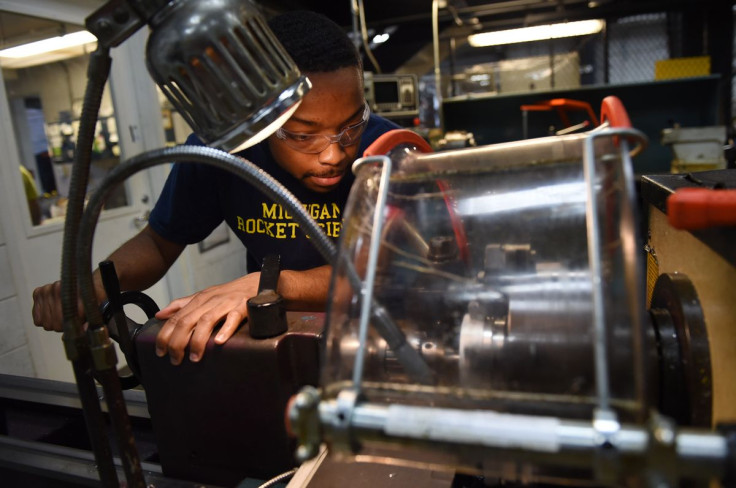

Mann, at the time a 21-year-old Morehouse College student with a 3.96 GPA, had only two years of physics and pre-engineering classes under his belt, while most of the other interns had at least two years of engineering classes, which meant more hands-on lab experience. The work itself was high-stakes: testing critical components of rocket engines that would one day take cargo and astronauts into space.

“There is this misconception that you snap your fingers and take a company like Intel and make it diverse — it doesn’t happen that way."

“Basically, what I had to do is seek assistance from people at the company -- other people who had the insight I hadn’t learned in my classes,” said Mann, who is now 23. “I had to get to a place where I could believe I was there for a reason, that I could succeed.”

In Silicon Valley parlance, a “unicorn” is a startup valued at more than $1 billion, but Mann represents another rarity: a black engineer working in tech. One year after tech giants like Google, Facebook, Microsoft and others started issuing “diversity reports,” initially at the behest of the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the percentage of blacks employed at tech firms remains embarrassingly low.

Silicon Valley likes to paint its diversity problem as one of supply: There simply aren’t enough blacks getting advanced degrees in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, also known as STEM, in the U.S. And while that is true, it is also true that tech firms are not tapping existing engineering talent. Even the most diverse Silicon Valley tech firms are at 2 percent or under in terms of blacks in technology jobs, yet across the U.S. blacks earned 4.4 percent of master’s degrees in engineering and 3.6 percent of its Ph.D.s in 2014, according to the American Society for Engineering Education.

It amounts to about 4,897 newly minted black engineering grads each year, including civil, electrical and mechanical engineers, as well as software engineers -- the kind Silicon Valley would most like to hire. Blacks also earned 4.5 percent of undergraduate computer science degrees and 2 percent of master's degrees, comprising about 745 graduates, in 2013, the last year for which data are available, according to the Computer Research Association.

Somewhere, the pipeline of black and other minority candidates and jobs in Silicon Valley is broken. “If you look at the numbers in Silicon Valley, 1 or 2 percent African-American, there is still a gap given the numbers coming out of college with degrees in computer science,” Karl Reid, executive director of the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE), said.

It is broken in part because Silicon Valley is not looking in the right places, and black students interested in STEM careers are choosing other industries that have been more welcoming, such as oil and gas, automotive and civil engineering. It’s a challenge that tech firms in Silicon Valley and Seattle face as they attempt to raise the percentage of blacks from the current 1 percent or 2 percent to something that looks more like America, or the markets they’re trying to serve.

Today, Joshua Mann is 24 and finishing up his second bachelor's degree at the University of Michigan. In the spring he's starting a master's of science in aeronautics and astronautics at Purdue University, the latest in a series of steps toward his dream: a job designing rocket engines that could one day take humans to Mars.

If Mann makes it to a job in tech -- one of the most segregated sectors of the U.S. economy -- it will be the latest in a legacy of achievements for his family, which started in the United States five generations ago on a slave plantation in Louisiana.

Mann’s maternal great-great-great-great-grandparents, William and Rosaline Daly Smith, were slaves on the John Andrus farm, a 125-acre tract along Bayou Boeuf in St. Landry’s Parish. Their son, “Papa” Dave Smith, born in 1873, had just two years of schooling, yet he found a way to scrape together the money to actually buy the farm he was born on in 1916.

He did it by working the very land his parents did and making it produce, as he liked to say, “by the sweat of his brow.” “His earnestness of purpose, of determination, plus his willingness to work, won respect for him from people of his own race and many white friends in St. Landry’s Parish,” a story in the Daily World in Opelousas, Louisiana, stated on his 93rd birthday in 1966. The farm has been in the Smith family for the past 99 years, and for the past 68 years the family has returned to it every other year for a reunion.

Four generations later, Mann’s mother, Tammy (Smith) Mann, was the first in her family to go to college. She graduated from Spelman College in 1987 and later earned from a Ph.D. from Michigan State. Mann's father was also among the first in his family to go to college, getting an undergraduate degree from Wayne State University and a master’s degree from George Washington University.

Today that family history sits stored in Joshua Mann’s mind, not frequently accessed but available when needed for motivation.

“I don’t think of myself every day as a descendent of slaves, or as member of a family that was able to purchase a farm that my ancestor was a slave on. I don’t go through those thought processes every day,” he said. “They are part of my history, and I do feel as though I have the responsibility to at least honor those sacrifices made before me and take advantage of the opportunities I’ve been given.”

Mann was born in Detroit, but his family settled in northern Virginia for job opportunities. As a high school student in Fairfax, Virginia, Mann had uncanny focus: He knew he wanted a career in aerospace engineering. He also noticed that as he took more and more advanced science and math, he was often the only black student in the classroom. “When I notice these things, it doesn’t trigger me emotionally; I objectively note it scientifically,” Mann said.

But it did play into his decision to go to Morehouse rather than a “name” engineering school like Stanford, MIT or even the University of Virginia. “I decided to go to Morehouse because I wanted to interact with black people who were just as serious and passionate about working hard and challenging themselves as I was,” he said.

Mann also wanted to build on a short family tradition at historically black colleges. "My mom was a Spelman [College] grad,” he said. “She graduated across the street [from Morehouse]. She could tell me about the experience and value of going to an all-black school.”

While Silicon Valley has made efforts to recruit at historically black colleges and universities, some say they aren't doing enough to build connections to institutions that graduate black engineers in large numbers. “Many of the firms in Silicon Valley are not seeking minority engineers where they are being produced,” said Gary S. May, dean of the College of Engineering at Georgia Tech, which produces more black engineers than any other institution in the U.S. “They’re are still recruiting in Silicon Valley at Stanford and Berkeley. That is where the company founders and executives were educated, and that’s where they know to look.”

According to the NSBE, 28 percent of all engineering degrees awarded to blacks are earned at historically black colleges and universities. Google has said 35 percent of its black engineers come from historically black colleges, one reason the company expanded its Google in Residence program, which places Google employees in college classrooms, to five more institutions last fall: Howard University, Hampton University, Fisk University, Spelman College and Morehouse College.

But the NSBE's Reid said tech has to move beyond the most famous historically black institutions to find talent. “If you ask them their target colleges and universities, they tend not to name Claflin University in Orangeburg, South Carolina, or Tougaloo College in Mississippi, which have a strong history of sending grads into STEM," he said. "You typically don’t hear about these schools.”

As good as Morehouse is, it is not the most direct path to a job designing rocket engines, which requires both a heavy engineering education and preferably hands-on experience building and testing rockets. Morehouse has no engineering program in-house; rather, it has a partnership with nearby Georgia Tech that allows physics majors to take engineering classes.

“I knew Morehouse had a great physics program but no engineering, so I knew this was going to take a little longer,” he said.

Enrolling at Morehouse meant that he would spend his first two years doing physics coursework, not the engineering training that would make him competitive for aerospace internships. To gain some experience, Mann volunteered in a research lab at Georgia Tech. A professor there, Mitchell Walker, himself an aerospace engineer, wrote Mann a recommendation that got him considered for that first internship at SpaceX. “I would not have had the opportunity if Mitchell Walker had not put his name on the line and said, ‘This kid can make it at SpaceX,” he said.

Mann ended up doing two summer internships at Space X. Last summer he was the only black summer intern accepted at Blue Origin, the Kent, Washington-based rocket startup founded by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. The internship is competitive: Last summer 350 candidates applied, and 18 were selected. “I calculated a 5 percent chance of acceptance,” he said.

When Mann arrived at Blue Origin, he felt he was welcomed and his contributions valued. “Engineers would come up to me and say, ‘I’m really glad you’re working on that project,” he said. “I also noticed the fact that I was one of the few black people they ran into on a day to day basis.”

It’s not that there weren’t black people at Blue Origin; they just weren’t in engineering roles, the kind Mann hoped to one day achieve. “We have people who are mechanics who turn the bolts and screws, plenty of black people doing those jobs,” he said. “But when you get into engineering and look at engineers across the company, I was one of two, and I’m just an intern.”

That's one experience just about every black engineer has had over and over: the feeling of being the only one in the classroom or the workplace. "What I consistently hear is the isolation they feel; even if they are really smart they are the only one or two," said Gerald Harris, a longtime tech executive and investor in Mayvenn, a startup that provides black hair supplies to salons.

"I had some experience with this," Harris said. "I went into the power industry in 1978. I was the first African-American in the finance department at PG&E. I know what it feels like to be the only person there."

As unique as Mann was at both SpaceX and Blue Origin, he actually represents a significant problem for Silicon Valley as it attempts to diversify its tech ranks. While Mann has coding skills, he’s not a software engineer, which the likes of Google, Facebook and Twitter will need to attract to move the diversity needle. “Mechanical and electrical engineering tend to be the No. 1 and No. 2 disciplines in our population, and we have 220 chapters,” Reid said.

However, he said, even those engineers could be good candidates for tech jobs, but they're often overlooked. “It’s not what you learn that matters; it’s how you learn and how you solve problems,” Reid said. “That is classic engineering education.”

At Georgia Tech, May said his graduates are more likely to land high-tech jobs in Texas, North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park or in Boston than in Silicon Valley. “We have great relations with some Silicon Valley companies -- Intel, for example -- but if you want to make a general statement the big companies could do a better job recruiting here,” he said.

The Bay Area’s demographics are also playing a role. The communities where Silicon Valley’s biggest tech companies are based can feel unwelcoming to blacks in particular. San Francisco, for example, had seen its black population fall to under 6 percent in 2010 from 7.8 percent in 2000. The Bay Area's black population fell to 6.7 percent in that timeframe, down from 7.5 percent in 2000, according to the U.S. Census.

"If I am black and I went to school in Atlanta and grew up in Detroit and I come to Silicon Valley for an interview and get to my hotel in Palo Alto and go to a restaurant, there is nobody black there. Then I go to the company and nobody on the interview team is black and nobody in the lunchroom is black,” said Ken Coleman, a longtime Intel exec and chairman of big-data startup Saama Technologies.

"Then I drive around and there are no black neighborhoods and ask myself, 'Is this going to be conducive to who I am and who I want to become?'" he said.

Minority recruits often find the interview process daunting, particularly if they have technical degrees in areas other than computer science. “In many interviews they actually ask the students to code in the interview,” Reid said. “If you have not had the experience or knowledge of the language or syntax you are not going to do as well. But can you do well? That’s the question.”

It’s clear that Silicon Valley must cast a wider net for talent if it plans to move the needle on diversity. But how?

At Saama Technologies, Coleman is focused on creating a diverse talent pool, but also on training programs for STEM grads to look outside the traditional talent pools. This was partly to create a diverse workforce but partly a necessity: “There aren’t a lot of programs that produce data scientists,” he said.

So Saama started recruiting candidates with quantitative skills in math, physics, statistics or even psychology and put them into a four-month paid program to train them to become long-term hires. “That allows us to get very smart people who can do our work who might not have computer science degrees,” he said.

“We make sure we have a diverse pipeline, and we take the 20 best kids,” Coleman said. “My experience is if you have a diverse applicant flow and an unbiased selection process you will naturally get a diverse set of employees.”

Until Jackson started agitating in 2013, most of the tech industry did not consider diversity a problem that needed to be solved. Yet now big tech companies, both public and private unicorns, are facing a real challenge of improving their diversity figures even a single percentage point.

“There is this misconception that you snap your fingers and take a company like Intel and make it diverse -- it doesn’t happen that way,” Coleman said.

What Intel did do is establish a goal last year to achieve “full representation” in Intel’s workforce of the “talent available in America.” It’s an amorphous goal that’s been picked apart by various critics. When the Washington Post asked Intel to clarify, Intel Chief Diversity Officer Rosalind Hudnell said, "The technical workforce can only mirror those people that are going into technology."

But as modest as that goal is, not having a goal is worse. “You have a metric for everything that matters,” Coleman said. “It has to have an objective, deliverables and reporting. That is the way you manage everything else in the enterprise that is important.”

But beyond the embarrassment that annual “diversity reports” are causing, there’s a growing fear that Silicon Valley’s lack of diversity will become a liability in the global marketplace. “Diverse teams end up producing better products,” Reid said. “A diverse sales force has access to a diverse client base. Companies are realizing this is not a charity, moral or ethical issue -- it affects the bottom line.”

“Diverse teams end up producing better products. A diverse sales force has access to a diverse client base. Companies are realizing this is not a charity, moral or ethical issue -- it affects the bottom line.”

The arguments for a diverse workforce make intuitive sense: An engineering team with diverse backgrounds is more likely to find an innovative solution than a homogenous team. Employees that reflect a community are more likely to understand its dynamics and create better products. Indeed, in a global marketplace, lack of diversity could be seen as a competitive liability.

That logic has certainly taken root in Silicon Valley. "I think the most diverse group will produce the best product, I firmly believe that," Apple CEO Tim Cook told Mashable in June. “And so if you believe as we believe that diversity leads to better products -- and we're all about making products that enrich people’s lives -- then you obviously put a ton of energy behind diversity the same way you would put a ton of energy behind anything else that is truly important."

But more than poor products, there's the notion that Silicon Valley is missing markets altogether. Take Mayvenn, which raised $10 million over the summer in an initial round of venture capital funding led by venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. No surprise here that Mayvenn's founder, Diishan Imira, is a black graduate of Hampton University who grew up in a family full of hairstylists. "Nobody in Silicon Valley would have thought of this -- I can guarantee you that," Harris, the Mayvenn investor, said. "People told him they don't even know any black women. He was told that several times."

Research has shown that diversity correlates strongly with better business results. One of the latest examples came from McKinsey & Co., which published a study in January that looked at corporations across the world economy and found that diverse companies were 35 percent more likely to perform above the national median in a given industry, versus the nondiverse. What’s more, each additional 10 percent of racial and ethnic diversity on senior executive teams in the U.S. equated with 0.8 percent higher earnings before interest and taxes.

What studies don’t show is whether a diverse workforce was what caused better results or if a diverse workforce is the happy result of better performance. “While correlation does not equal causation (greater gender and ethnic diversity in corporate leadership doesn’t automatically translate into more profit), the correlation does indicate that when companies commit themselves to diverse leadership, they are more successful,” the authors of the McKinsey study wrote.

In Mann’s case, the system may yet work. He managed to find his way from talent and potential to a series of internships navigating his way through a leaky pipe that leaves behind engineering talent. Mann did not come from a school that typically supplies the high-tech industry. On paper, he did not yet have the skills. Yet three years later, he’s shed some of the insecurity that he felt first walking into SpaceX.

“Regardless of how I got there, I must have done some pretty good work to get invited back,” Mann said of SpaceX.

For all the prestige of working at Blue Origin this past summer, it taught him something important about what he wants to do and what it will take to get there.

Soon after he arrived, Mann learned he would not be working with the engineers who design rocket engines. Rather, he would be working with a group testing materials going on the rocket itself. To do that, he built testing hardware and used coding skills to speed up the process “so they can test over twice as much materials as they could before.”

“I got put on a task that I could do well but was not necessarily my passion,” Mann said.

But the experience crystallized his vision for what he really wanted to do -- test and build rocket engines. The master's degree from Purdue will get him into chemical rocket propulsion; electrical propulsion, the kind that could power interplanetary travel, requires a Ph.D. But one step at a time: Mann is committed to another two years of school, but he's hoping the next internship leads to the full-time job he’s been dreaming about since he was in high school, at a place like SpaceX, Blue Origin or Boeing.

Mann doubts his race will be a deciding factor in finally getting hired. With recent high-profile mishaps, the private space industry has more pressing concerns than diversity as it attempts to shoulder a greater portion of the U.S. space program from NASA. Anything but focus on the final product can lead to catastrophe that could set back the space program or even cost lives.

Ultimately, Mann sees work in rocketry as potentially Earth-saving as extraction industries such as mining are potentially moved to other planets, preserving our home planet for future generations.

“When I see ‘Star Wars’ I don’t see it as child stuff,” Mann said. “I get to go to my desk to work and build spaceships that will one day take people beyond anything that we know. Everything is possible when you get to space.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.